Of the many human characteristics keenly observed in “The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected),” the most powerful is the lonely sense of being the only something in one’s family. The only failure, the only daughter, the only one with no artistic talent—these are traits that, whether incontrovertible or questionable, are clutched like well-earned badges of honor by the Meyerowitz brood. The siblings fling their Purple Hearts with reckless abandon, sometimes to curry favor and other times to wound. These battles play out for the benefit of a father who, as the children should know by now, is too self-absorbed to really take notice. But a win, no matter how Pyrrhic, is still a win. In the never-ending battle of the sibling, the stats matter.

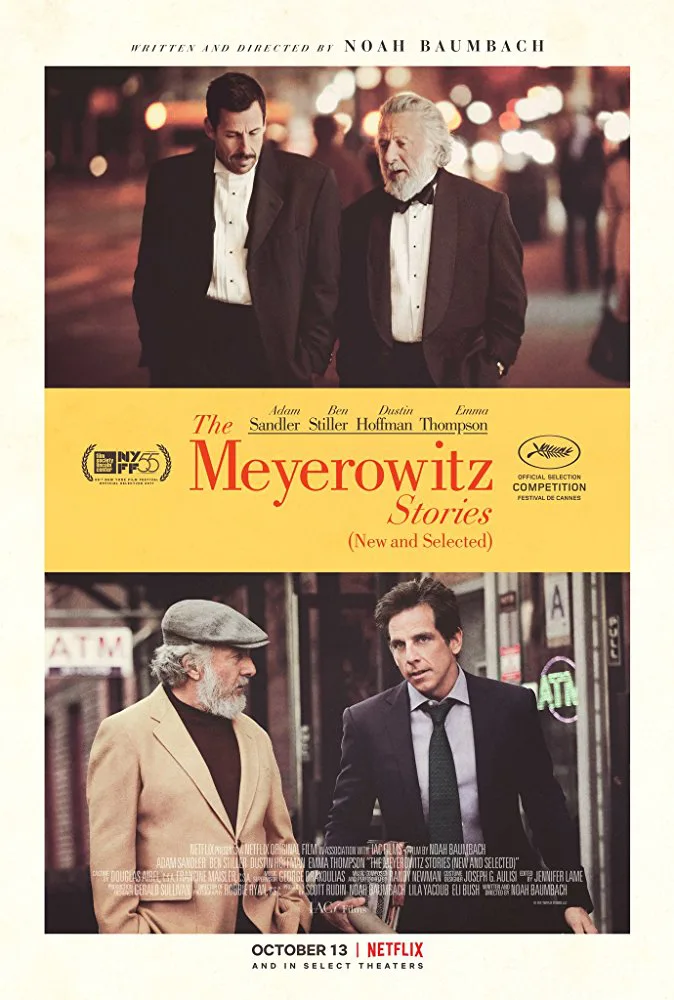

Dustin Hoffman plays Harold Meyerowitz, the family patriarch whose multiple marriages produced three children, Jean (Elizabeth Marvel), Matthew (Ben Stiller) and Danny (Adam Sandler). Like Gene Hackman’s Royal in Wes Anderson’s “The Royal Tenenbaums,” Harold possesses a charm that draws people toward him before his dark side keeps them at bay. Hoffman adds another layer to this familiar archetype, a comic brittleness that pricks the viewer like a cactus touching a balloon. No other actor is more masterful at conveying this kind of aggravating self-righteousness, whether aggressively or passively, than Hoffman. With Harold, everyone else’s feelings are secondary or non-existent, and in the rare moments he’s completely present and on your side, it still feels as if he’s there under duress.

It’s no wonder Harold’s children have issues. We first meet Danny, who is trying to find a parking space in the no-parking wonderland that is the East Village. Danny’s college-age daughter Eliza (Grace van Patten) has accompanied him on this visit to her grandparents’ house. This father-daughter relationship is far cozier than the one Jean has with Harold; Danny seems to be a self-consciously less antagonistic parent. The duo bond over a song on the radio and commiserate about the obnoxious New York drivers whose impatience keep wrecking Danny’s parking opportunities. Later, we’ll see that Eliza also has a good relationship with her uncle and especially her aunt.

Danny’s opening vignette sets the pattern for how “The Meyerowitz Stories” will operate. A title card appears, then a scene builds to a crescendo before abruptly being cut off by another segment. Some of the cuts are hilariously rendered, others feel like interruptions in one’s train of thought. But the gimmick is always well-executed and suggests that we’re privy to several interconnected short stories being told to us by writer/director Noah Baumbach.

We learn that Harold has had some modicum of success as a sculptor, though lately he hasn’t been as prolific as he was in his youth. Though a self-proclaimed failure, Danny appears to be the only one of his children who inherited some form of artistic creativity. He’s a songwriter who plays piano. Danny sings two songs written by Sandler, Baumbach and Randy Newman, who also provides the score. One of the songs is a lovely ditty about the relationship between Danny and Eliza. The other pokes fun at a faux pas Harold committed at one of his art shows. Coincidentally, Harold’s old university wants to put on a show featuring his sculptures—a move championed by Danny—but Harold doesn’t want to share the spotlight.

After introducing Danny and briefly highlighting his struggles with Harold, “The Meyerowitz Stories” pivots to Danny’s half-brother, Matthew. He’s only mentioned in passing in Danny’s first vignette, and he gets his own set of scenes with Harold before the film merges their plotlines. Unlike Danny, Matthew was no good at anything arty and instead has become a very powerful, very successful financial planner. Matthew ran for the shores of Los Angeles as soon as he could, and didn’t look back. When “The Meyerowitz Stories” takes Harold temporarily out of the picture due to a health scare, a deeper antagonism is revealed between Matthew and Danny. Matthew wants to sell Harold’s current house, a house Danny is attached to despite the fact he did not grow up there. Danny is angry at his brother for leaving.

As the two battle for control and the audience’s sympathy, Baumbach reveals several symbolic comparisons between the two men: Danny has a bum leg but Matthew’s neuroses are just as crippling. Matthew is rich and miserable while Danny is a failure but can at least find a ray of sunshine in his daughter. Eventually, the brothers come to blows in a wrestling match that’s so garish and true-to-life it will immediately conjure up memories for any guy who has a brother.

Observing all this, and occasionally contributing to the story, is Jean. The way “The Meyerowitz Stories” often demotes its funniest character to the sideline is a calculated, though not always successful, attempt at portraying Jean’s odd-man-out status as the only daughter in the Meyerowitz clan. She and Emma Thompson, as Harold’s hippie-ish drunk of a fourth wife, get some of the biggest laughs but still feel underutilized. Baumbach almost makes it up to Marvel when Jean finally gets her own title card and story, the result of which pulls the siblings together in an act of childish mischief disguised as revenge. It’s not enough, however; Marvel is so good in the role that one longs for a lot more of her.

Unlike his prior work, Baumbach is surprisingly humane here. He beats up on his characters, but he also gives them a salve to help heal the wounds. His charity extends to minor characters like Harold’s more successful rival (Judd Hirsch in an endearing cameo) and Harold’s first wife, (Candice Bergen, who gets a great monologue). Baumbach has also finally written a role for Stiller that doesn’t inspire outright hatred. But “The Meyerowitz Stories” shockingly belongs to Sandler, who is absolutely fantastic.

Sandler finds the perfect line between tragedy and comedy for Danny. He still does his hollering angry man-child shtick, but here it stems organically from the character and is never used as a comedic crutch. Additionally, he shades his performance with subtleties both physical and verbal. Some of his best moments involve just a facial gesture or a well-placed pause. His interactions with the other characters are rife with complex emotions unlike any he’s played before. Exasperation, joy and forgiveness flow through him in perfectly calibrated measures. It’s a rich, surprising performance.

With its often overwhelming familiarity, the subgenre of dysfunctional family dramedies has negated Tolstoy’s notion that every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. While “The Meyerowitz Stories” is yet another one of these movies, it does manage to circumvent some of the more predictable clichés. It also manages to succeed when it occasionally succumbs to them. This is one of the year’s best movies.