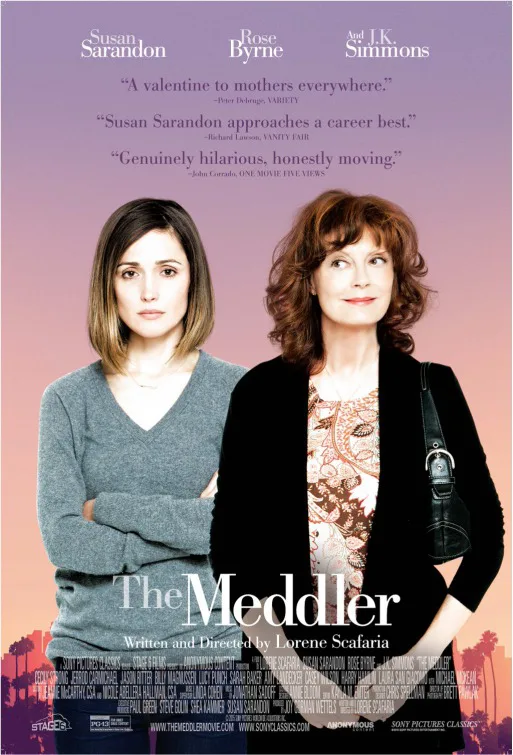

“The Meddler” is a diminutive and misleading title for such an affecting, often profound film. Susan Sarandon plays the title character, Marnie Minervini, a sixty-something mom who moves from New York to Los Angeles to be closer to her screenwriter daughter Lori (Rose Byrne), who just broke up with her actor boyfriend (Jason Ritter). Marnie is one of those mothers who calls her daughter five times in the space of a couple of hours, leaving a message each time Lori doesn’t pick up, then leaves ten more messages throughout the day because she’s worried about not having heard back from her yet. Her daughter can’t take her relentlessness, so Marnie channels her energy into mothering strangers and near-strangers. She encourages a helpful Apple store clerk named Freddy (Jerrod Carmichael) to go to college and even gives him rides to and from school. When she finds out that a young lesbian mom named Jillian (Cecily Strong) can’t afford her fantasy wedding, she offers to foot the bill herself.

This description makes “The Meddler” sound like a lighthearted mother-daughter bonding movie with a hint of romance for Marnie, who is courted by two divorced men, Michael McKean’s earnest, nerdy Mark and J.K. Simmons’ divorced ex-cop Zipper, who tends chickens, rides a Harley and plays guitar. And it is all of those things. But in its heart, it’s a story about the lived experience of grief. Marnie is still dealing with the death of her husband, and Lori with her father. This dear man, Joe, is seen only in photographs, but he is the absent presence looming over both women and driving many of their choices. The script is filled with details so expertly observed and so rarely seen in Hollywood films that you suspect they came from experience.

And they did. Writer-director Lorene Scafaria (“Seeking a Friend for the End of the World“) based the film on her and her mother’s experience after her father died. She must have kept a detailed journal. Every few minutes there’s an image or observation that rings true to actual grief, as opposed to movie grief, such as the way that Marnie hesitates while checking a box on a form because the only “marital status” options are married and single; or the way the soundtrack fills up with Joe’s beloved swing and 1950s doo-wop when Marnie gets lost in a reverie for him; or the scene where Marnie’s therapist suggests that she’s burning through the money Joe left her because she feels that it’s a consolation prize for losing him, and Marnie blankly denies it even though she’s sitting on a couch piled high with bags from Crate and Barrel. When Marnie visits Joe’s family in New York and casually says it’s been a year since Joe died, they correct her: it’s been two. That’s what happens to your perception of time when you’ve lost someone close to you. Seeing it captured onscreen in such an offhand way is miraculous.

This is not remotely a “downer” movie, but it’s not chirpy or coy, and it doesn’t sugarcoat anything. Scenes that might play as superficially cuddly or heartwarming in other movies have a piercing undertone because of the weight that Marnie and Lori carry but rarely discuss. When Marnie hangs out with Zipper—a silver fox with a mustache and a baritone drawl who politely informs her that his ride is not a motorcycle, but a Harley-Davidson—it’s not just a meet-cute that’s being delayed so that the film won’t be over in half an hour. Marnie is hesitating because in his own laid-back California way, Zipper reminds her of Joe, and she doesn’t know if she can love a man like that again. You can tell Zipper gets this even though he doesn’t know the details, just by the way he listens to her: with patience and serenity.

These truths and others come through strongly in the writing and in the performances, in particular Sarandon’s. She struggles at first with the character’s New York accent but seems to understand the character on a deep level, right down to the way she gets stoned and seems to “conduct” a fountain, or the way her expression unfolds in wonder and gratitude when she watches a scene in her daughter’s TV pilot and realizes it’s drawn from their lives, and that Lori has transformed her own suffering into art and momentarily resurrected Joe through her writing.

Scafaria has made a kind, smart, special film. Like “Terms of Endearment” and the underappreciated “Once Around,” it takes place in reality and deals with real feelings, many of them unpleasant or scary, but always with honesty and empathy and knockabout humor. Its touch is not light, it’s delicate. A lot of people are going to be surprised by how deeply this movie understands them. In its modest way, it has much to say about what it means to move through catastrophe, one step at a time.