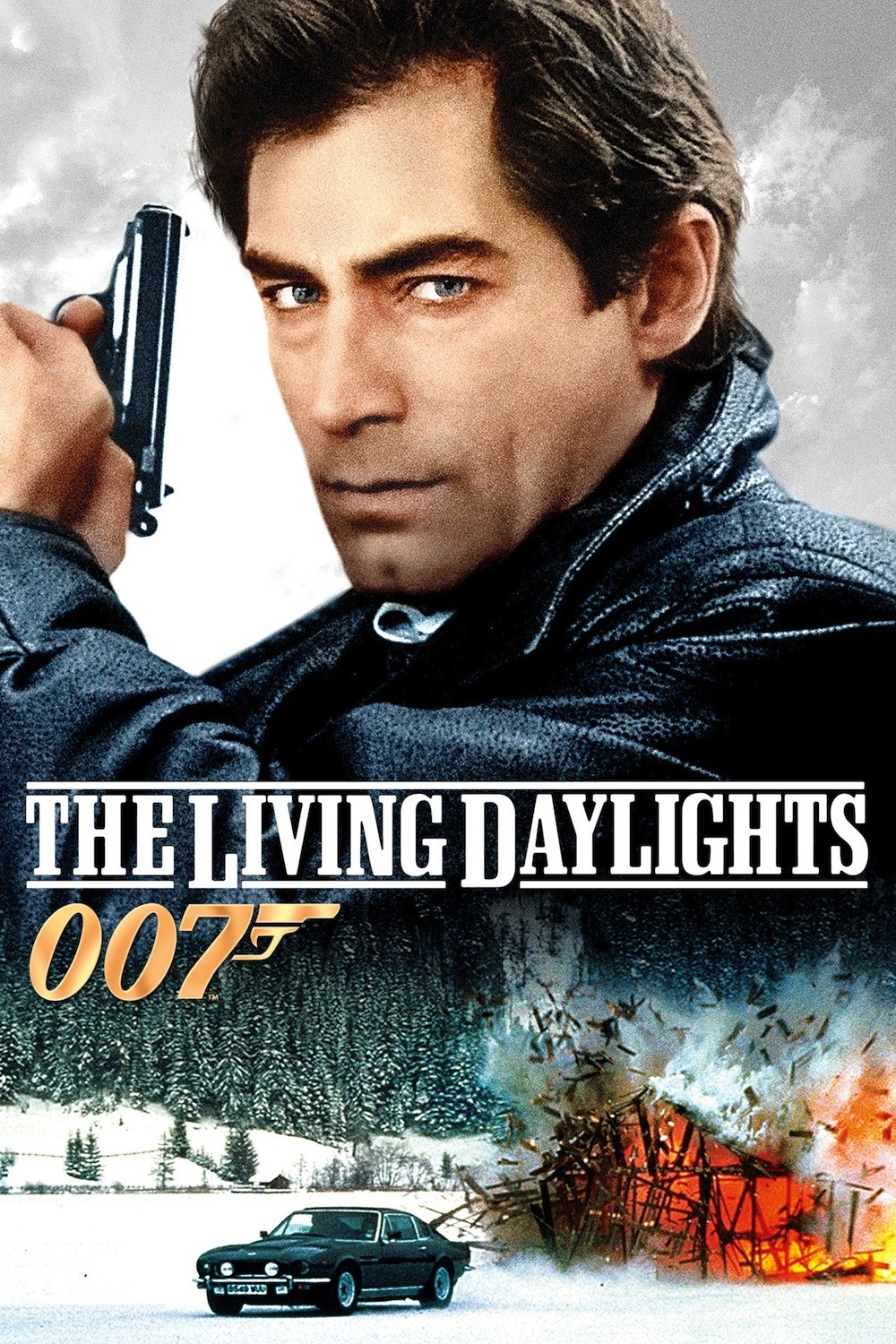

The raw materials of the James Bond films are so familiar by now that the series can be revived only through an injection of humor. That is, unfortunately, the one area in which the new Bond, Timothy Dalton, seems to be deficient. He’s a strong actor, he holds the screen well, he’s good in the serious scenes, but he never quite seems to understand that it’s all a joke.

The correct tone for the Bond films was established right at the start, with Sean Connery’s quizzical eyebrows and sardonic smile. He understood that the Bond character was so preposterous that only lightheartedness could save him. The moment Bond began to act like a real man in a real world, all was lost. Roger Moore understood that, too, but I’m not sure Dalton does.

Dalton is rugged, dark and saturnine, and speaks with a cool authority. We can halfway believe him in some of his scenes. And that’s a problem, because the scenes are intended to be preposterous. The best Bond movies always seem to be putting us on, to be supplying the most implausible and dangerous stunts in order to assure us they can’t possibly be real. But in “The Living Daylights,” there is a scene where Bond and his girlfriend escape danger by sliding down a snow-covered mountain in a cello case, and damned if Dalton doesn’t look as if he thinks it’s just barely possible.

The plot of the new movie is the usual grab bag of recent headlines and exotic locales. Bond, who is assigned to help a renegade Russian general defect to the West, stumbles across a plot involving a crooked American arms dealer, the war in Afghanistan and a plan to smuggle a half-billion dollars worth of opium. The story takes Bond from London to Prague, from mountains to deserts, from a chase down the slopes of Gibraltar to a fight that takes place while Bond and his enemy are hanging out of an airplane. The usual stuff.

One thing that isn’t usual in this movie is Bond’s sex life. No doubt because of the AIDS epidemic, Bond is not his usual promiscuous self, and he goes to bed with only one, or perhaps two, women in this whole film (it depends on whether you count the title sequence, where he parachutes onto the boat of a woman in a bikini). This sort of personal restraint is admirable, coming from Bond, but given his past sexual history surely it is the woman, not Bond, who is at risk.

The key female character is Kara (Maryam d’Abo), the Russian cellist, who gets involved in the plot with the Russian general, tries to work against Bond and eventually falls in love with him. As the only “Bond girl” in the movie, d’Abo has her assignment cut out for her, and unfortunately she’s not equal to it. She doesn’t have the charisma or the mystique to hold the screen with Bond (or Dalton) and is the least interesting love interest in any Bond film.

There’s another problem. The Bond films succeed or fail on the basis of their villains, and Joe Don Baker, as the arms-dealing Whitaker, is not one of the great Bond villains. He’s a kooky phony general who plays with toy soldiers and never seems truly diabolical. Without a great Bond girl, a great villain or a hero with a sense of humor, “The Living Daylights” belongs somewhere on the lower rungs of the Bond ladder. But there are some nice stunts.