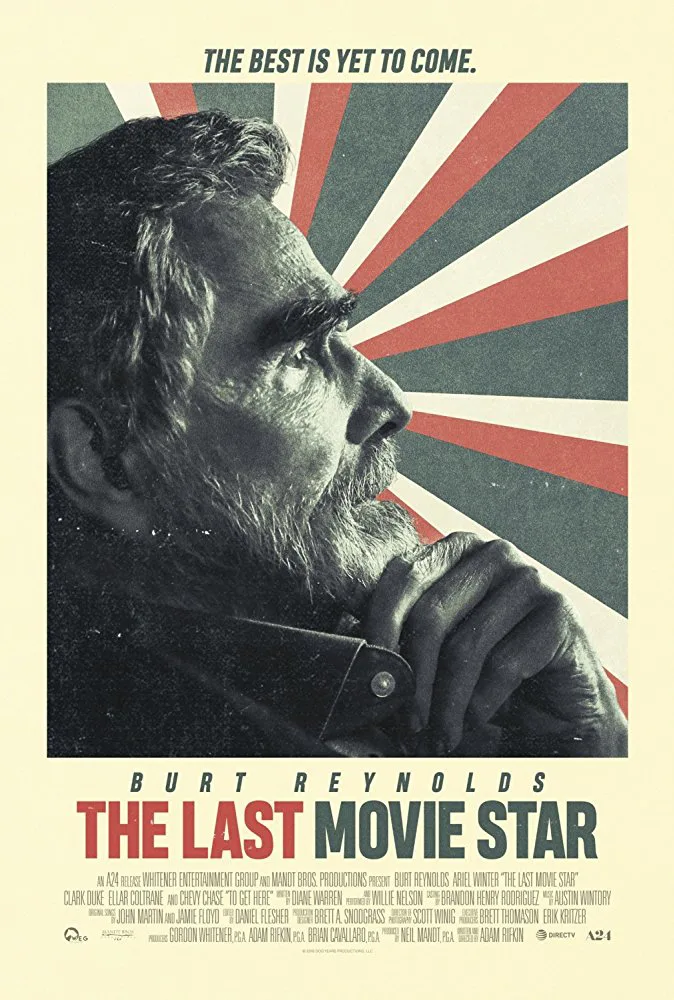

Adam Rifkin’s “The Last Movie Star” is designed not just as a vehicle for Burt Reynolds, but as a meditation on Reynolds’ fame. Using elements of Reynolds’ actual biography, including footage from Reynolds’ films, “The Last Movie Star” is the story of an actor who, despite his fame and good fortune, feels he never quite lived up to his potential. Maybe he could have had a more “serious” career if he had taken some risks. This is Rifkin’s point of view, too. “The Last Movie Star” thrums with Rifkin’s urgency, similar to Linda Loman’s comment at the end of “Death of a Salesman”: “Attention must be paid.” (Some of us never stopped paying attention to Reynolds, but never mind.) As a commentary on Reynolds’ career trajectory, “The Last Movie Star” is hit-or-miss. What is undeniable, though, is the space Rifkin has created where Reynolds can do what Reynolds does best, and if you’re a fan (as I am) there’s much here to treasure.

When Vic Edwards (Burt Reynolds), a 1970s-era movie star who now lives a quiet lonely life as an old man, arrives at the “International Nashville Film Festival” to accept a Lifetime Achievement Award, he is chagrined (and furious) to discover that the fest was thrown together by a trio of 20-something film geeks, and hosted in the back of a bar. His “personal driver” is a loud-mouthed Goth girl named Lil (Ariel Winter), who has no idea who Vic is, and doesn’t care. To Vic, the low-rent festival seems a commentary on his career failures. On opening night, with a small crowd of eager movie fans in attendance, he gets wasted and lashes out during the QA session. Reynolds doesn’t soft-pedal any of this. Vic is a jerk.

Vic demands Lil take him to the airport immediately, but on their way there, he asks her to detour to Knoxville, his birthplace. So begins Vic’s journey down memory lane, with Lil in tow, who spends most of her time arguing with her abusive boyfriend on the phone. Vic visits the small house where he grew up. He visits the football stadium where he was a champion. Slowly, over the course of the road trip, Lil softens up, Vic gives her fatherly advice, while making peace with unfinished business in his past.

In a couple of sequences, Rifkin puts current-day Reynolds into footage from Reynolds’ actual films, with dialogue molded to fit. So Vic sits in the passenger seat of the car in “Smokey and the Bandit,” urging his wild younger self to take life a little bit more seriously. Or he lies in the canoe in “Deliverance,” watching his younger self shoot fish with a crossbow. There’s an eloquent moment where Vic really takes in the biceps, the sexy forehead-wrinkle of his younger self, and comments, almost startled, “Damn, you’re good-lookin’.” It’s not a moment of vanity. It’s like saying, “The Grand Canyon is big.”

I liked these meta-moments. (Rifkin even throws in a reference to Reynolds’ famous nude spread in Cosmopolitan.) I liked them because they gave Reynolds an opportunity to reflect, in a way he has rarely been asked to do. He’s an old man. He’s trying to make sense of his life. Rifkin using Reynolds’ actual life as fodder for the film results in electric moments like Vic staring at the empty football stadium, and saying, “It’s fun being a movie star, but nothing compares to being a football star. Nothing.” Reynolds doesn’t need to “act” that line. He knows it in his bones.

Reynolds, in his heyday, had an effortlessly masculine charm and a goofball sense of humor. If that killer combo could be bottled, it would be worth millions. But it can’t be bottled, an actor just has to have it. Burt Reynolds had it. He became a star after years in Hollywood as a stuntman and a bit player in B-Westerns and television series. He was likable, gorgeous, and charming. A gorgeous man who doesn’t take himself seriously (or at least appears to not take himself seriously), who lampoons his own stardom, who doesn’t strain for the brass ring of respectability (and Oscars), who is happy “just” entertaining his fans … this was the magic elixir of Reynolds. He was one of the best Johnny Carson guests ever. He didn’t come on to plug his projects, or if he did, the “plug” soon went out the window because he was too busy shaving off one side of his mustache or squirting whipped cream into Carson’s crotch (a clip Rifkin uses in “Last Movie Star”). Reynolds was what he was, and he was the biggest sex symbol of his day doing it.

The question “The Last Movie Star” seems to pose is: Would Reynolds’ career have been better if he had taken on grittier parts? I don’t think so, not necessarily. Reynolds acted from pure natural charisma, something unique to him. It won’t win Oscars, but Oscars do not equal actual worth. If you think being “charming” is easy, then walk into a party where you don’t know anyone and try to be as charming as Reynolds. He committed the “crime” of making it all look easy.

Burt Reynolds did a Turner Classic Movie tribute video for Spencer Tracy, his favorite actor. He met Tracy in 1959 while working on a television series. Tracy was filming “Inherit the Wind” on a nearby soundstage, and Reynolds would sneak over every day just to watch Tracy work. One day, the two struck up a conversation. Reynolds recalls, “I told him that I was trying to be an actor and Mr. Tracy said, ‘Well, don’t let anybody catch you at it. Don’t act. Just behave.’ I felt like I was being knighted. That advice was so true.” It was advice Reynolds clearly took to heart. Whether doing a playful sexy duet with Dolly Parton in “Best Little Whorehouse in Texas” or romancing Jill Clayburgh in “Starting Over” or whooping it up with Jerry Reed in “Smokey and the Bandit,” Reynolds was at home in his own skin. In “Deliverance,” he is a natural Alpha male, without huffing or puffing with effort. He was terrific in “Semi-Tough,” “Best Friends,” “The Longest Yard,” films suited to his sensibility. Robert De Niro gaining a lot of weight for “Raging Bull” has become a measuring-stick for what good acting should look like, but there are many ways to have a career, and Reynolds’ career was a throwback to an earlier type of fame, fame based on personality or essence. “Boogie Nights,” of course, gave him the chance to step into a—pater familias—space, while still utilizing his powerful sexual persona, bringing with him the “hangover” of his 1970s-era superstardom.

The hangover is still present in “The Last Movie Star,” something Rifkin relies on. I may disagree with Rifkin’s take on what “went wrong” in Reynolds’ career, but Reynolds himself seems to have misgivings about his choices along the way. Rifkin has given Reynolds opportunity to let us see what it’s like to be him, and Reynolds does so without strain, without pleading for sympathy, just an exhausted acknowledgement of his own truths. His quiet monologue where he “says goodbye” to Knoxville is so beautifully clear and true it seems “captured” rather than “performed.”

Reynolds holds the center of “The Last Movie Star.” He lets us see aspects of himself left out of the kinds of roles he normally played, aspects like insecurity, thoughtfulness, regret, grief, helplessness. If you want to know why Reynolds is great, watch him when he’s listening to someone talk. There’s one scene in the car where Lil, at the wheel, rattles off her lengthy and byzantine pharmacological history. Rifkin places the camera on the driver’s side of the car, with Lil in the foreground and Vic in the passenger seat. Rifkin never cuts. The monologue goes on forever, and your eye keeps going to Reynolds’ face, listening to her talk. In his listening, Reynolds doesn’t “comment” on what he hears. He doesn’t telegraph to us his reaction to the drug-cocktails. He is in the moment. Total focus on her. When she finally finishes, there’s a slight pause, and he says, calmly, still looking at her, “Should you be driving?”

That’s Burt Reynolds.