There is an island of dying animals in the Philippines named Calauit that exists in its current state because of the unchecked opulence of Imelda Marcos. She wanted animals in the Philippines who weren’t native to the country, and officials were bribed to make that happen. It is a perfect symbol for her insidious, egocentric, blinding greed in that it is the kind of landscape-changing thing people with power and wealth do without considering the consequences. Director Lauren Greenfield, our best filmmaker when it comes to documenting the extremely rich in movies like “Generation Wealth” and “The Queen of Versailles,” returns to this island a few times in her excellent “The Kingmaker,” recognizing how its almost haunted nature symbolizes the ghosts of the past of her subject, Marcos herself. Intercutting interviews with Marcos and her son with archival footage and other experts on the Marcos regime, Greenfield has put together a haunting reminder that those who have extreme power rarely if ever consider the consequences of their actions—in fact, they often think the word consequences shouldn’t apply to them. Take what you will from the film in terms of timeliness for the current American political situation, but parallels to unchecked power around the world feel intentional and add depth to “The Kingmaker.” We could all be on an island of dying animals if we’re not careful.

I have to admit to being concerned when “The Kingmaker” began. Was this going to be a reclamation project for a controversial political figure? Would we be shown that the public image of a woman with rooms full of shoes was really a complex leader? At first, it feels like an attempt to humanize Marcos, with early scenes of her throwing money at any problem, including children in a dilapidated cancer ward, although that quickly turns. If documentaries like “The Kingmaker” often makes their subject relatable, this film shines a spotlight on an insane degree of ego, corruption, violence, and gross greed. As the film goes on, Greenfield doesn’t watch Marcos continue to dig herself into a deeper hole, she keeps handing her bigger and better shovels. By the end, Greenfield has assembled one of the most insightful portraits of what is basically sociopathic behavior excused by wealth and privilege that a documentary has ever produced.

Imelda Marcos would have you believe that her wealth was not only earned but good for the Philippines. She speaks in early scenes about how far Manila has fallen from her time in power; she hands out money to poor people; she laments the better times for her country under the power of her husband Ferdinand. Greenfield does allow for a bit of humanizing early on as we learn about the loss of Marcos’ mother at a young age and the emotional toll Ferdinand’s infidelity took on her. But one can almost sense the filmmaker starting to see through Marcos’ image control even in these early scenes. As she details the corruption that forced the Marcos regime to fall—by some estimates, the Marcos family stole $10 billion from its own people—she contrasts the false narrative that continues to be presented by her subject over and over again.

What emerges is a study in propaganda and revisionist history. Marcos would have you believe her husband was a great leader who helped his country, that her son is the future of the Philippines (legacy means the world to her), and even that she ended the Cold War. Greenfield starts to turn her camera away from Marcos and to the people who suffered because of the decisions made by her and her husband Ferdinand Marcos, and the result is harrowing and moving. When Greenfield gets to the horror stories of how political enemies were raped, assaulted, tortured, and killed, “The Kingmaker” becomes something less like “Queen of Versailles” and more like “The Act of Killing.” And the filmmaking here is Greenfield’s best. Note how she films these scenes in sparse rooms and often with no score, allowing us to lean in and listen, contrasting them against the lavish rooms in which she speaks to Marcos.

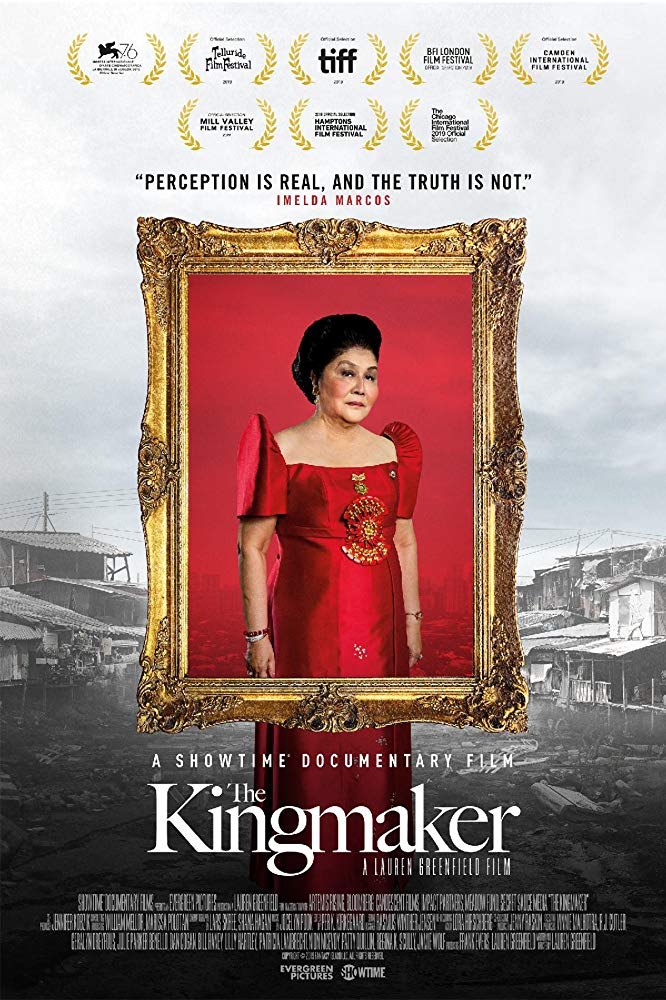

“Perception is real, and the truth is not,” says Marcos. She is a master of denial and image manipulation to such a degree that it feels like she believes her lies. Corruption and fraud may be the “truth” but that doesn’t matter nearly as much as the image she presents for her people. It’s the “perception” that defines her, and it’s way more important than anything that could be considered true. Perhaps the most disturbing thing about “The Kingmaker” is that Marcos’ attempts to rewrite history seem to be working in some ways. And one could argue that image control led the country to where it is now under the Duterte regime. The story of the Marcos legacy isn’t over, but “The Kingmaker” is a major chapter in it, and world politics as a whole.