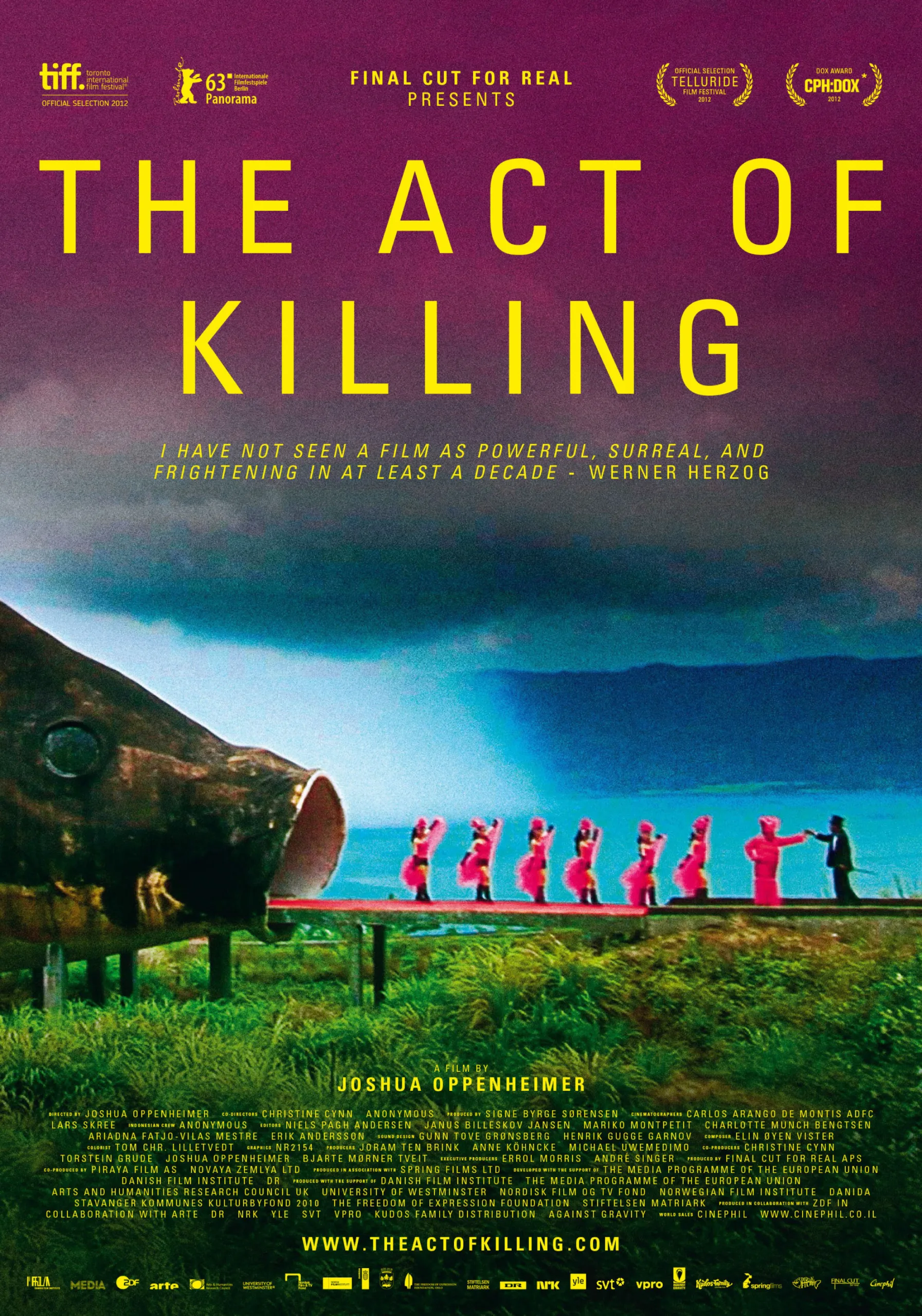

Killing is not necessarily a cold business, and killers are not necessarily cold-blooded. “The Act of Killing” introduces us to several Indonesian mass murderers who could be movie stars. They jump at the chance offered by this documentary’s maker, Joshua Oppenheimer, to make their own movie, a chronicle of their years carrying out an anti-Communist purge that claimed over a million lives in 1965-66. When the military recruited them as muscle, they became the most feared and sadistic of the liquidators. But they did it all in style: Notorious killer Anwar Congo points to a black-and-white photo of young man who looks like a sleek hybrid of Charles Bronson and Smokey Robinson: “That’s me. I’m wearing a plaid shirt, camouflage pants, saddle shoes…” He advises the film’s costumer not to dress him like that for the massacre scenes. “I wore jeans for killing. To look cool, I imitated movie stars.”

Still fit and spry in his sixties, Congo uses the film to confront facts long denied publicly and long sublimated personally. He and his pals believe that no court, from local authorities to the International Criminal Court, can prosecute them for their crimes 40 years after the fact. This gives them the confidence to deliver unguarded performances for their movie and offer astonishingly candid testimony for Oppenheimer’s. Yet almost every night, Congo says, some of the hundreds of victims he killed with his own hands visit him in his dreams.

One of the more excruciating recurring motifs here is the sight of present-day civilians doing their best real-life acting whenever these gangsters are around. Indonesia may have returned to a semblance of democracy after strong man Suharto’s resignation in 1998, but the murderers still control politicians and business leaders.

And the people still fear them. Chinese shop keepers and market vendors who are old enough to have been around when their people were indiscriminately included in the purge are forced to smile wide while handing protection money over to Safit Pardede, arguably the vilest of the gangsters in the film. (Later on, while taking a break from filming a reenactment of a village massacre, he reminisces wistfully with his buddies about raping fourteen year-old girls. “I’d say, ‘It’s gonna be hell for you but heaven on earth for me!'”) Such moments made me wonder whether I was watching yet another reenactment, since it seems pretty crazy for a thug to openly admit crimes on camera.

It appears that longstanding corruption has solidified into a core Indonesian principle, like democracy or capitalism. We see politicians make speeches proudly declaring that they are gangsters, careful to remind the crowd that the term “gangster” in their society only means “free man.” A leading newspaper publisher brags about how he manufactured evidence against suspected Communists, providing long lists for the death squads. This is the smiliest atrocity documentary I’ve ever seen.

Between camera setups on the historical film, Congo’s neighbor Suryono shares a story about watching the death squads abduct his communist stepfather. Quick to reassure the gangsters that “I’m not criticizing what we’re doing,” he describes finding his stepfather’s body under an oil barrel the next day. At 12 years of age, he had to help bury his stepdad in a roadside ditch. Moments after this recollection, Oppenheimer keeps the documentary camera focused on Suryono, whose cavalier facade is crumbling by the second. He seems to implode as Congo’s friend Adi Zulkadry, a flinty veteran executioner who reminds me of Ray Winstone, browbeats the others about sugarcoating their crimes: “Everything Anwar and I have always said is false. It’s not the communists who were cruel. I’m absolutely aware that we were cruel.”

This seemingly odd compulsion to confess becomes the film’s (and the film-within-the-film’s) grandest special effect. We are witnessing nature’s justice, a force of law more precise than the courts. It squeezes the truth out of these guys, who can’t seem to shut up about what awful people they are and how incessant partying, self-medication and relatively prosperous family lives keep them from facing their crimes squarely. Denial comes as naturally as breath, in perpetual tandem with convulsive shame. When that doesn’t do the trick, there’s always relativism: Says Zulkadry, “When Bush was in power, Guantanamo was right. [Bush claimed] Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. That was right, according to Bush, but now it’s wrong. The Geneva Conventions may be today’s morality but tomorrow we’ll have the Jakarta Conventions…”

The historical film-within-a-film doesn’t seem to have a lavish budget, but it does appear lovingly crafted by a discerning, resourceful crew. The reenactments strive for brutal accuracy while a few fantasy sequences give the impression of a comical telenovela co-directed by John Waters and Alejandro Jodorowsky. Congo’s pal, the portly, vicious but hilarious paramilitary leader Herman Koto, even appears in outrageous beauty-queen drag, an Indonesian Divine.

There’s never been a shortage of dark, grim documentaries that catalog life’s cruelty, horrors and banality of evil. Thanks to the documentary genre, I have watched hundreds of hours of war crimes, genocides and miscarriages of justice carried out by unremarkable men with dimly lit souls. “The Act of Killing” bids to outdo them all. I’m not sure even the film’s powerhouse executive producers, Werner Herzog and Errol Morris, have ever presented cognitive havoc so densely yet elegantly packed into one documentary.

The visual and aural rhythms of this one feel as if Oppenheimer is slowly, carefully climbing a mountain of lament and shame, each footfall made with absolute certainty that there’s solid, (if jagged and painful) rock underneath. When we arrive at the top, the view is majestic in its sadness. From this vantage point, the last half hour of “The Act of Killing” surveys a divinely art directed stretch of hell. It looks familiar, a place of law and order and malls and McDonalds. Doting grandfatherhood has brought out the gentleness in Congo, whose beautiful smile and gentle laugh lines make him resemble Nelson Mandela (rather than the dictator his friends say his dark skin evokes, Idi Amin).

Watching his finished film with his grandsons, he begins to understand something essential about himself and his victims. Oppenheimer seizes the moment, posing a question that knocks the wind right out of him. This masterpiece about propaganda, cinema and vanity as instruments of power and terror ends on an excruciatingly sustained, righteous money shot: a monster who could have been a good man suffocates on the truth.