What we desire is not a happy ending, so much as closure. That often means simply that a film knows what it thinks about itself. “The Killer Inside Me” is expert filmmaking based on a frightening performance, but it presents us with a character who remains a vast empty lonely cold space. The film finds resolution there somewhere, perhaps, but not on a frequency I can receive.

Michael Winterbottom’s film is inspired by a 1952 pulp novel by Jim Thompson, perhaps the bleakest and most unrelenting of American crime novelists. The book is considered by some his finest work; other Thompson novels were filmed as “The Grifters,” “The Getaway” (1972), “After Dark, My Sweet” and “Coup de Torchon.” Stephen King wrote: “Big Jim didn’t know the meaning of the word stop. There are three brave lets inherent in the forgoing: he let himself see everything, he let himself write it down, then he let himself publish it.”

What Thompson saw in his character Lou Ford (Casey Affleck) was a mild-spoken, intellectual psychopath with no understanding of good and evil. He murders people he loves, while loving them, and has no idea why. The story’s insights into this seem limited to the title. There is a killer inside him. The killer is not him. He doesn’t understand that killer. He has no control over him, and no doubt sincerely regrets the killer’s crimes.

The story is set in west Texas in the early 1950s. Lou Ford, narrating his own story, is a deputy sheriff in a rural town. He still lives in the home where he was raised. In the evenings, he plays classical piano, reads books from his father’s library and plays opera recordings.

His voice, high-pitched but rough, bespeaks innocence. He has a girlfriend named Amy (Kate Hudson). He has the respect and affection of his alcoholic boss, Sheriff Bob Maples (Tom Bower). He is unfailingly calm and pleasant.

One day, Maples gives him a job: Drive a few miles outside town and have a word with the prostitute Joyce (Jessica Alba). A powerful local developer, Chester Conway (Ned Beatty), is concerned about her influence on his son, Elmer (Jay R. Ferguson). Ford pays the visit, has some words and soon the two of them are urgently having rough sex. Why? Because this is the pulp universe, where a woman may be a prostitute with other men but she finds you irresistible. Female psychology is not the strong point with many pulp writers. Psychology in general is sketchy, based on simplified and half-understood Freudian notions. With Lou Ford, for example, we’re given fragmented glimpses of childhood sexual abuse. Not the sort of abuse we’ve seen before: His mother liked Lou to slap her.

Indeed, Lou seems to attract women who like to be beaten. One apparently even likes to be nearly killed. The film attempts to account for this no more than it explains Lou’s own nature. The best explanation probably is: When you buy a cheap paperback with a lurid cover, these are the sorts of events that will be described inside. In prose, the focus is through the point of view. In the film, we see the violence happening, and the first time it comes as a gut punch, because we’re not remotely expecting it.

Not from Lou Ford, anyway. Casey Affleck, an effective actor, is so convincing with his innocent, almost sweet facade that the movie sets us up to expect he’ll be solving a crime, not causing one. He maintains that facade in the face of the most compelling challenges, not only from his own violence, but from two people with excellent reasons to suspect him: a labor leader (Elias Koteas) and the county attorney (Simon Baker). When Lou actually confesses to a kid who admires him (Liam Aiken), even what happens then doesn’t phase him.

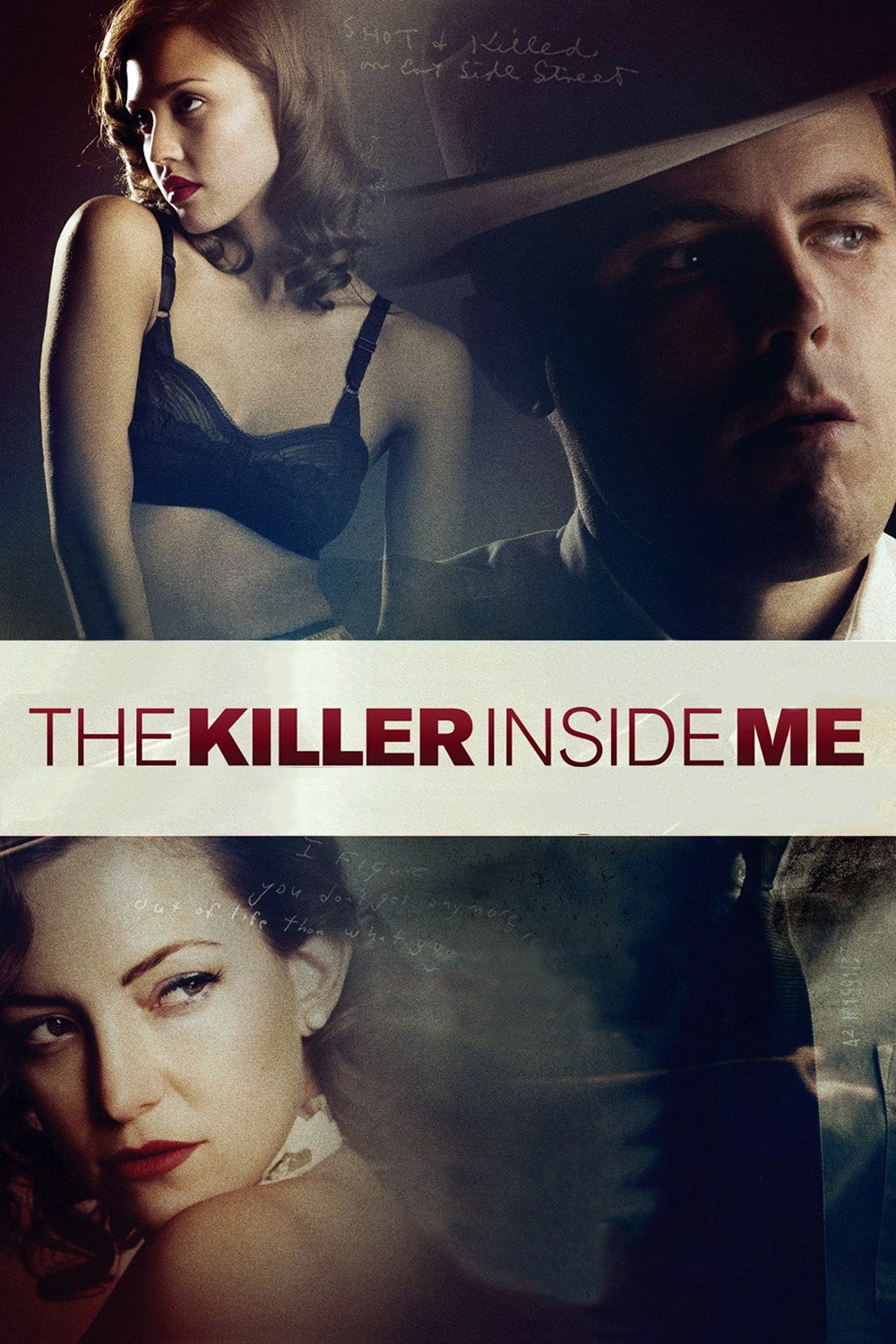

There is a point beyond which Lou’s implacability brings diminishing returns. While I admire Affleck’s performance, I believe Winterbottom and his writer, John Curran, may have miscalculated. The reader of a pulp crime thriller might be satisfied simply with the prurient descriptions, and certainly this film visualizes those and has as its victims Jessica Alba and Kate Hudson, who embody paperback covers, but the dominant presence in the film is Lou Ford, and there just doesn’t seem to be anybody at home.