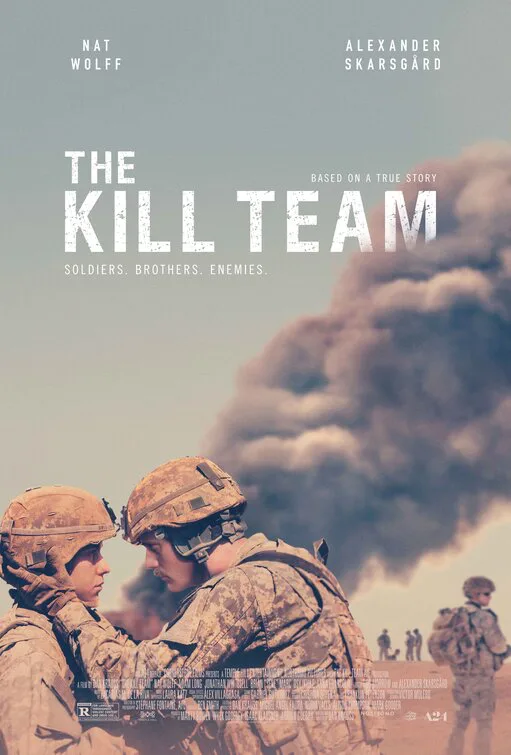

“The Kill Team,” writer/director Daniel Krauss’ dramatization of actual wartime atrocities by U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan, is lean, sincere, impassioned filmmaking, yet it fails to leave as much of an impression as it clearly wants to.

Part of the problem is that the movie, while focusing on unique events, takes a form that’s too reminiscent (sometimes knowingly so) of other American movies about military atrocities, particularly Brian De Palma’s “Casualties of War” and “Redacted” and Oliver Stone’s “Platoon” and “Born on the Fourth of July.” It focuses on Nat Wolff’s Private Andrew Briggman, an eager young soldier who falls under the spell of a magnetic, soft-spoken but viciously dominating sergeant (Alexander Skarsgård’s Deeks), helps cover up war crimes committed by the squad, then thinks about endangering his own safety by turning whistleblower. Krauss, a cinematographer and journalist, is adapting his own, same-titled documentary about a real-life case from 2009 and 2010, wherein a group of U.S. Army soldiers killed civilians for no defensible reason and conspired to hide their crimes from higher-ups. That one was more about the aftermath and consequences, and this fictionalized version is about the atrocities themselves and the military culture that contributed to it.

There are two major problems, though. One is that the casting is good but rarely spot-on; this lessens the impact of the film’s many tense and/or violent situations because the actors either aren’t electrifying enough to take the confrontations into the stratosphere or else Krauss never quite figured out how to guide them to that place. The biggest letdown is Skarsgård, who seems to be going for “stone killer” but often seems merely stoned, letting his extreme height and glassy-eyed “just try it” expression carry too much of the character’s psychic and (a)moral weight.

Wolff does the best he can with a blank slate male ingenue part, which, to be fair, anchors the other, superior movies I’ve cited higher up, blanding out moments that needed more than earnestness and moral confusion. The supporting characters register more strongly, but don’t have enough spotlight moments to lodge in the memory. The major exception is Adam Long’s Rayburn, a grinning bully and troublemaker who immediately positions himself as Deeks’ strong right hand. Long has a fire-starting gaze and razor-edged smirk, like a baby Lee Marvin; in some scenes, he dominates his costars so thoroughly that you might wonder if he might’ve been a better choice for Deeks, despite his youth.

It’s might not be fair to the movie to say this, considering how closely it hews to real and thoroughly reported events, but there are too many familiar beats planted in too many expected spots on the timeline, and even the best acting can’t stop you from returning to an unpleasant fact: all of these characters are types of one sort or another. The widescreen cinematography (by Stéphane Fontaine, a regular collaborator of Jacques Audiard) is not inspired enough to carry the film past its rough patches; it’s your standard handheld panoramic battle zone imagery, reminiscent of “The Hurt Locker,” which was released the same year that this movie is set in, but with somewhat more attention paid to framing and color.

In the end, the truth proves to be more arresting than its fictional mirror, a conundrum that has only been experienced by a handful of directors who directed both the dramatizations of true stories and nonfiction accounts of same. (Michael Apted’s “Incident at Oglala” and “Thunderheart” are a similarly mirrored pairing.) Even if you haven’t seen the documentary version or read up on the events they summarize, you might still feel as if you’re getting something less than the fullest, most arresting picture of what went down.

The film also has little awareness of the Afghan people as individuals rather than victims or pawns. And it seems unwilling to question the idea that a war can have rules and the code of honor, and it doesn’t delve too deeply into the idea that what the soldiers did was an atrocity measurably worse than the occupation itself. But these qualities are characteristic of many American war films throughout history. Somehow war is always a thing that happens to Us, even if we are doing it to Them.