You have to hand it to Jean-Luc Godard: he’s 88 now and has been making movies since the late 1950s, but everything he makes in this late, hyper-experimental phase is still the movie equivalent of a drink you expected to be stiff but not that stiff.

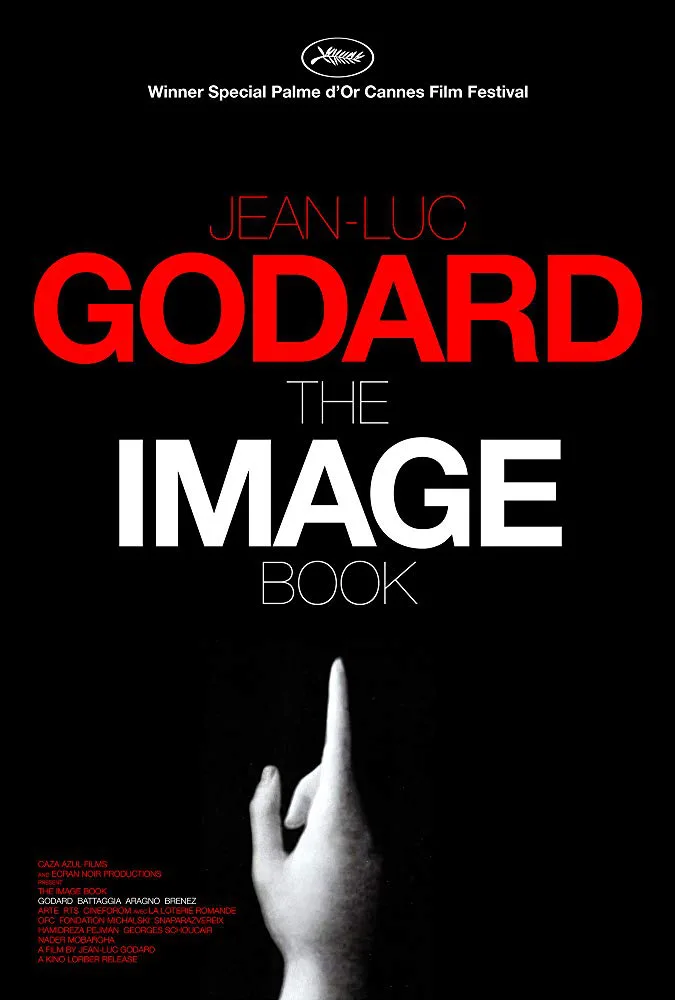

His latest work “The Image Book” starts with a closeup of a hand pointing a finger upward, followed by closeups of text shown on an old-fashioned video display terminal, then a pair of hands cutting film on a 20th century Steenbeck editing table, and two more pairs of hands writing words on paper. By the time it ends, it has ruminated on the rise of the image, the fall of the word and the pulverization of every form of information into a nonstop stream of “content;” drawn connections between the mechanization of genocide during the Holocaust and colonization; created a kind of self-contained film-within-a-film, romanticizing the Arabic-speaking world through four decades’ worth of movie clips; and handed viewers a continuous analogy for the film’s own stylistic techniques by grouping together dozens of clips from movies involving trains (“trains of thought,” perhaps?).

But what is “The Image Book” about, you ask? Or maybe you don’t, if you’ve seen a Godard film made after about 1980.

Godard, one of the original pioneers of the French New Wave, has been an international celebrity for decades, and a controversial one. He’s feuded with some of the major figures in world cinema and major film festivals, and with luminaries in the arts and politics. He’s been a vocal activist for Palestinian causes and has been accused of anti-Semitism, always insisting that he’s anti-Zionist but not anti-Jewish; the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which gave Godard an honorary award in 2010, said in a statement, “”Antisemitism is of course deplorable, but the academy has not found the accusations against Godard persuasive.” In interviews about his movies he comes across as alternately prankish and sour, well-read and a bit of a charlatan, somewhat like Orson Welles back in the day. He conducted a press conference at the 2018 Cannes film festival via iPhone. For the 2005 press conference for “Notre Musique,” he invited a representative of the French Actors and Technicians Union to appear in his place, then sat in the audience while a list of grievances against the French government was read.

None of this will necessarily inform your appreciation of “The Image Book”—except maybe the Zionism part, and only in a roundabout way; the Arabic section plays like a semi-coherent love letter to a region and its artists, albeit one that frequently oversimplifies and renders exotic the thing being praised. As I’ve said in previous writing on this director, Godard’s montage films are best experienced as a direct tap into the restless mind of the director who wrote, directed, produced, and edited them, and also narrated, in the portentous, croaky voice of a fairy tale creature muttering prophecies from a bog. It moves in fits and starts, deliberately. Even more so than in other recent Godard essay movies, the images, dialogue, music, sound effects, black screens, and moments of silence seem to operate at cross-purposes.

As hard as it is to assign star ratings to certain movies, it’s even harder with a work like “The Image Book,” a free-associative meditation on language, the image, extinction, and a lot of other things. The movie itself often seems to be disintegrating as you watch it, or trying and failing to cohere. Godard is one of those directors who can’t really be evaluated in relation to other filmmakers, only to himself, so distinctive and often impenetrable is his style. Just as it’s difficult to articulate why certain Robert Altman, Spike Lee or Terrence Malick films hit your sweet spot and others do very little for you even though they’re using many of the same techniques, it’s hard to articulate why one post-millennial Godard picture comprised mainly of chopped-up film clips and discontinuous sound, dialogue and music hits the intellectual and visceral bulls-eye, but another leaves you cold.

Caveats aside, this is, in my estimation, a typically stimulating but opaque and deliberately frustrating late-period Godard film, good but not great, distinguished primarily by the fact that it’s the first Godard film to use no actors at all. But obviously, that tossed-off description won’t mean anything to a person who has never seen any others, or whose experience of Godard is limited to the handful of early Godard films that are still taught regularly in schools, like “Breathless,” “Contempt,” “Masculin Feminin” and “Week End.” And I wouldn’t want to discourage anyone who has never seen a film like this before and wants to give it a go, as long as they know what they’re in for.

The editing piles moments upon moments and thoughts upon thoughts, few of which are ever permitted to complete themselves. Godard deliberately builds in dozens, maybe a hundred transitions or moments of emphasis that in other films would be interpreted as technical errors or basic errors of competence. The sound drops out. The image freezes. The colors are so oversaturated that classic Hollywood film clips (many of them from films that Godard and his New Wave compatriots praised as critics) seem as if they could be 1980s music videos that had been recorded on VHS, badly damaged in a flood, then somehow inexplicably restored and added to Godard’s hard drive.

Some of the historical footage appears to have been taken from YouTube and up-rezzed, creating enormous pixillated bricks throughout the image; this was also a characteristic of Godard’s “Goodbye to Language,” and one wonders if he didn’t seek out better-quality material because he just doesn’t care about that anymore or because he finds the degraded image beautiful in its own way, or at least interesting enough to stand on its own and be stared at on a big screen, or a big TV, or a phone. I counted seven moments where the image suddenly changes aspect ratio from correct to incorrect, in the middle of presenting itself to us—this could be either a funny or sad way of getting across the idea that, when everything becomes content, or data, such distinctions scarcely matter anymore, so cinephiles might as well stop getting hung up on them. But it’s Godard, so who can say?

Intellectually, the movie is the opposite of rigorous. It’s all over the place, like an old and easily distracted uncle who keeps changing the subject. Unless you’re intimately familiar with every film, philosopher, political thinker, novelist, poet, and public figure quoted during the movie’s running time, it will be impossible to accurately guess why a certain image track was paired with another film’s soundtrack, or why a third piece of media suddenly came in—and it’s possible that even Godard can’t explain why he did certain things, because he’s never really been good at that, or interested in that. The supertitles are explanations that explain nothing, practically a joke on the idea of explaining things. The subtitles come and go. If you don’t speak fluent French, you’re going to miss a lot.

Or maybe you’ll sit back and experience this film, like so many late Godard films, as a primarily imagistic, sonic, and even physical experience, a battering and rearrangement of the senses, akin to a rollercoaster ride aimed at students of the humanities. I saw it twice and came away from it both times feeling discombobulated and sad and frustrated, because I felt like I was watching the entire history of civilization, and one of its most important filmmakers, fragmenting and imploding on the screen, ashes to ashes, dust to dust. But I also felt certain that Godard had put that opening finger on something—that in his halting, sometimes half-assed way, he’d found the pulse of an era, perhaps a civilization, in the process of dying, to be replaced by something we haven’t seen yet.