“The Hedgehog” is a feel-good movie that masquerades at first as a feel-bad. It’s narrated by Paloma, a precocious and almost infuriatingly self-assured 11-year-old, who plans to kill herself on her 12th birthday. This seems like a permanent solution to a trivial set of problems. Her complaints are common enough: Her mother talks to plants, her father is distracted by work, her sister is a snooty little snotnose, and her sister’s goldfish serves for Paloma as a metaphor for her own life lived in a bowl.

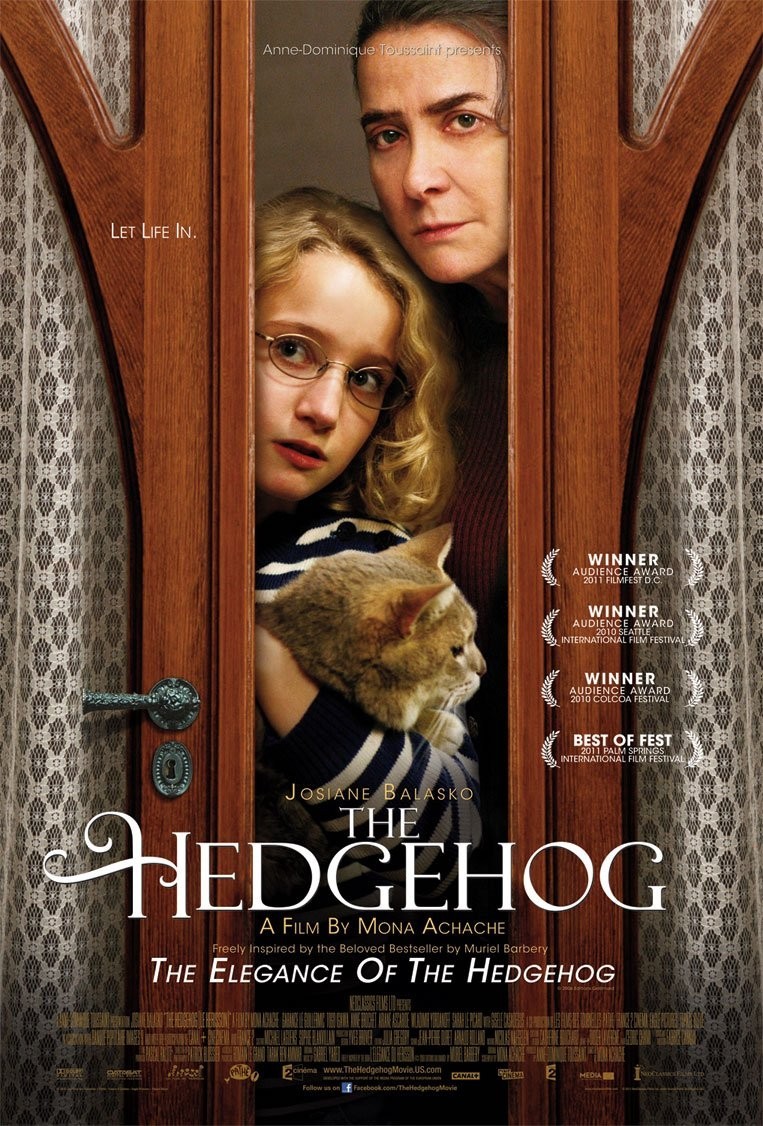

Paloma is the heroine of The Elegance of the Hedgehog, a French best-seller by Muriel Barbery. The hedgehog, as we know, is a creature that’s all bristles on the outside, and all cuddly on the inside. It is not Paloma who is the hedgehog in the film, but Madame Renee Michel (Josiane Balasko), the 54-year-old concierge of the Parisian apartment building where Paloma lives with her family. Madame Michel refers to herself as old and ugly, dresses in an almost aggressively dowdy fashion, and “doesn’t do anything with herself.”

At first, we fear the film will focus entirely on Paloma’s tiresome narcissism. Then a deus ex machina arrives in the form of Kakuro Ozu (Togo Igawa), who moves into an empty apartment. Mr. Ozu is an elegant Japanese man of around 60, and it should catch our attention that he happens to have the same surname as Yasujiro Ozu, that most civilized of Japanese directors.

We never learn very much about Mr. Ozu’s history. He arrives fully formed in the building, well dressed, quiet, his gray hair cut youthfully short. He overhears Madame Michel saying impatiently, “Happy families are all alike.” These are perhaps the most famous opening words of any novel, and Ozu supplies Tolstoy’s next line: “Every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

This is the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Mr. Ozu is apparently the first person in some years to regard Madame Michel’s bristly exterior and realize she is warm and good beneath the surface; feeling rejected by society, she has retreated to a small room in her apartment with her cat and her beloved books, and lives a life of the imagination.

There’s little that happens in the building that Paloma doesn’t observe, and often she records it on a video camera. This will presumably produce a document to explain her complaints about her family, and in particular, her feelings about the goldfish and why she has departed this life. But now a strange thing happens. She begins to see Madame Michel transformed by the quiet courtesy of Mr. Ozu, and she learns, by inference, that she must have more respect for her own warm insides and not be so fond of her prickly exterior.

“The Hedgehog” isn’t one of those movies where the heroine is transformed by a beauty makeover. The actress Josiane Balasko is not a beautiful woman, although of course she would be attractive if she permitted her face to advertise a sunny personality. We get a hint of this in a single smile, so small, so astonishing. I won’t go into the details of the polite relationship between the concierge and her new gentleman, nor will I mention a crucial event later in the film. All of that has to be experienced in context.

“The Hedgehog” is just a little too neat for me. Paloma is affected, Mr. Ozu is perfect to an unlikely degree, Paloma’s family exists as comic types, and Madame Michel comes closest in the film to simple plausibility. Still, this a movie with such a light, stylish touch, it makes no claims to profundity and is a sweetly hopeful experience.