So many documentaries follow such a rigid and predictable playbook that when you see one that’s trying to do something different, you cheer for it to succeed and feel sad when it doesn’t quite get there. The YouTube documentary “The Gift: The Journey of Johnny Cash” is that kind of documentary.

The filmmaker is Thom Zimny, a longtime editor who cut many Bruce Springsteen videos and concert films as well as 12 episodes of “The Wire,” and in transitioning to directing, he seems to be specializing in music documentaries of unusual ambition. Last year he premiered the epic two-part HBO documentary “Elvis Presley: The Searcher,” which ultimately cratered in its wild ambitions but was filled with subtle grace notes and long stretches that created an almost trancelike sense of being transported in a Presleyian headspace. This Cash project is another effort in that vein, and it’s so good when it’s doing things that no other documentary would think to do that when it switches back into a more traditional approach, the power seeps out of the movie. It’s as if a virtuoso guitar player had suddenly downshifted into licks you’ve already heard too many times. Yes, they’re skillfully played, but you still want them to go back to the stuff that was making your brain hum with possibilities.

The familiar licks are anything depicting Cash’s progress from cradle to grave, including his marriages, children, drug problems, spirituality and affinity for the dispossessed; Zimny handles the material deftly and the film has a knack for knowing when to move along to the next phrase of Cash’s life or art. But it’s still difficult to imagine a Cash aficionado who’s watched a few films on this topic (or broader treatments of American entertainment that treat Cash as one character among many, like Ken Burns’ recent “Country Music”) finding much here that’s new, either in terms of the information or the arrangement of archival footage (such as newsreel and TV footage, family photographs and mementoes).

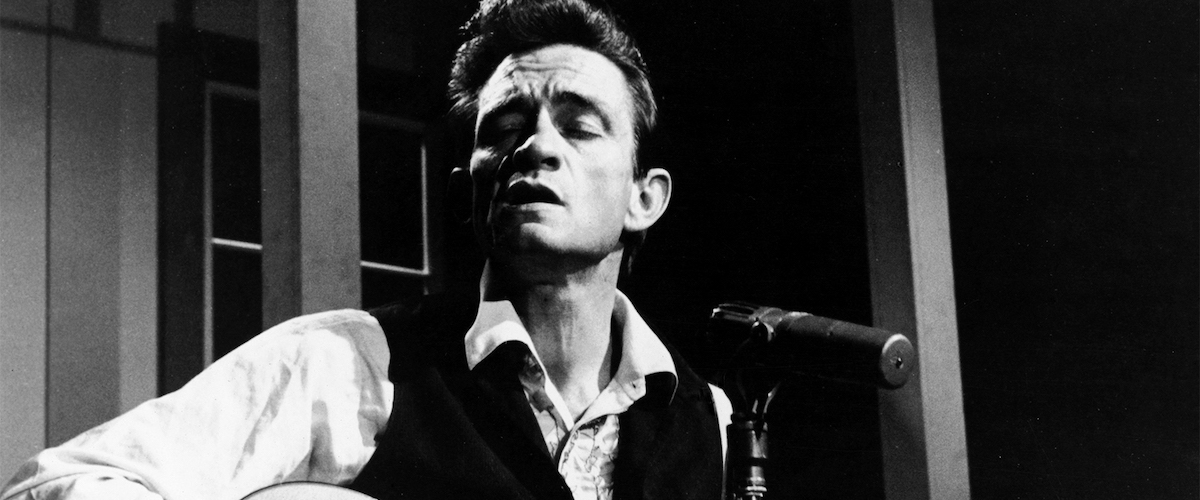

As in “The Searcher,” Zimny’ restricts Cash friends, family members, collaborators and scholars to audio-only interviews. This denies us the chance to see the faces of interviewees, including Springsteen, poet Robert Muldoon, Robert Duvall (who has great insight into Cash’s relationship with Christianity and sin), producer Rick Rubin, and Cash’s brilliant daughter and musical heir Rosanne Cash. But it creates richer possibilities for editing. The film is at its best when Zimny, his editors Chris Iverson and Brian Miele, and his cinematographers Charles Libin and Nicola Marsh seize these opportunities and squeeze them till the nectar runs out. These sequences in the movie fuse archival images with highly stylized and even surreal invented images that don’t so much re-create important moments in Cash’s life as try to poetically sum them up. The results are often glorious, even if their impact is muted by the venue where most viewers will experience the movie: i.e., on a laptop or phone.

The peak is an account of the death of Cash’s brother Jack at age 14, in a hideous buzzsaw accident that’s as central to Cash’s origin story as Elvis’ identical twin brother dying during childbirth (and that was parodied in “Walk Hard”). As Cash speaks of the tragedy in audio recordings that sound (based on the relative levels of gravel in his voice) as if they were captured at different periods in his life, the film shows photographs that are subtly distorted through focus shifts and editing filters, investing them the hazy potency of our own memories. Then comes the masterstroke: a shot of a train in the distance at night, chugging slowly towards the camera, its headlamp beam expanding to fill up the screen, creating an effect that evokes classical accounts of the tunnel of white light, while Cash’s voice-over quotes his brother’s deathbed description of a river flowing in two directions while an angel choir sang.

Other moments in “The Gift” are nearly as remarkable, such as the section dealing with the early years of Cash’s amphetamine addiction, accompanied by black-and-white shots taken through the windshield and side windows of a car careering down a winding road enfolded by dark woods. These flights of visual and sonic fancy are so unexpected and intuitive, as if a “what the hell, let’s try it” director like Terrence Malick or David Lynch had decided to make a music documentary, that whenever Zimny ramps down into a more traditional PBS-friendly vein—illustrating, say, an account of Cash’s doomed marriage to his first wife Vivian Liberto, with shots of the two of them looking contented and then distant or miserable, Cash’s activism on behalf of Native Americans with news photos on the topic and a snippet of John Wayne waging war against indigenous characters—it’s hard not to wish for more of the wilder stuff, even when the anecdotes and scholarship and musical analysis are compelling on their own merits.

The gear-shifting also creates some problems maintaining rhetorical through-lines. The film treats Cash’s progressive politics in a somewhat cursory manner when it isn’t tying them to his faith. And it never manages to untangle the relationship between Cash’s Folsom Prison concert, his own experiences with sin and failure, his guilt and trauma over his brother’s death, and the sense that he was called by Jack and God to preach the gospel through earthbound popular music, although various witnesses and Cash scholars sound so impassioned talking about this aspect of his art that you might feel as if the dots have been connected about as well as they could be.

More importantly, it’s impossible to watch what Zimny is doing in the most daring sections of these music documentaries, however fitfully, and not conclude that if he ever decided to construct a feature-length music documentary comprised of nothing but moments where he plugs into dream logic, the results could be mind-bending. And if that day ever arrives, let’s hope the film plays on the largest screens possible, with a sound system so potent that you feel Cash’s baritone in your marrow.