After Sean wrecks a construction site during a car race, the judge offers him a choice: Juvenile Hall, or go live with his father in Japan. So here he is in Tokyo, wearing his cute school uniform and replacing his shoes with slippers before entering a classroom where he does not read, write or understand one word of Japanese. They say you can learn through total immersion. When he sees the beautiful Neela sitting in the front row, it’s clear what he’ll be immersed in.

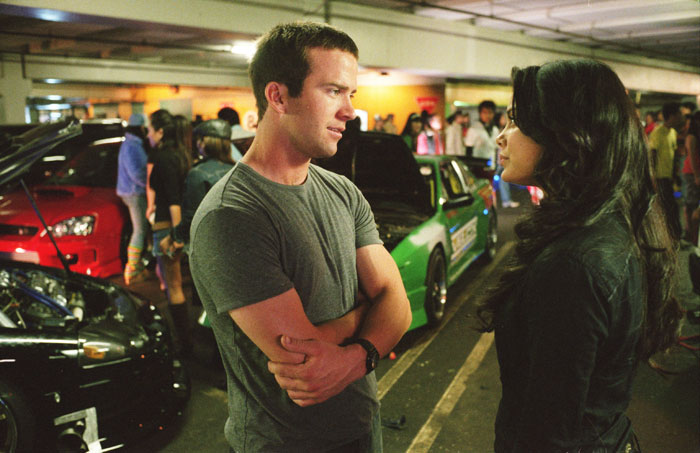

“The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift” is the third of the F&F movies; it delivers all the races and crashes you could possibly desire, and a little more. After only one day in school, Sean (Lucas Black) is offered a customized street speedster, and is racing down the ramps of a parking garage against the malevolent D.K. (Brian Tee), who it turns out is Neela’s boyfriend.

The racing strategy is called “drifting.” It involves sliding sideways while braking and accelerating, and the races involve a lot of hairpin turns. The movie ends with a warning that professional stunt drivers were used, and we shouldn’t try this ourselves. Like the stunt in “Jackass” where the guy crawls on a rope over an alligator pit with a dead chicken hanging from his underwear, it is not the sort of thing likely to tempt me.

The movie observes two ancient Hollywood conventions. (1) The actors play below their ages. Although the “students” are all said to be 17, Lucas Black is 24, and his contemporaries in the movie range between 19 and 34. Maybe that’s why the girls in the movie take their pom-poms home: They need to remind us how young they are.

They are also rich. After Sean wrecks the red racer that Han (Sung Kang) has loaned him, he has access to a steady supply of expensive customized machines, maybe because Han likes him, although the movie isn’t heavy on dialogue. “I have money,” Han tells Sean after the first crash. “It’s trust I don’t have.” He lets Sean work off the cost of the car by walking into a bathhouse and trying to collect a debt from a sumo wrestler. Meanwhile, in the tiny but authentic Tokyo house occupied by his father (Brian Goodman), a U.S. military officer, Sean has to listen to a movie speech so familiar it should come on rubber stamps: “This isn’t a game. If you’re gonna live under my roof you gotta live under my rules. Understood?”

Yeah, sure, dad. Sean is scorned in Tokyo as a gaijin, or foreigner, and that gives him something in common with Neely (Nathalie Kelley), whose Australian mother was a “hostess” in a bar and whose father was presumably Japanese, making her half-gaijin. “Why can’t you find a nice Japanese girl like all the other white guys?” Han asks him. Luckily Neely speaks perfect English, as do Han and Twinkie (Bow Wow), another new friend, who can get you Michael Jordans even before Nike puts them on the market.

The racing scenes in the movie are fast, and they are furious, and there’s a scene where Sean and D.K. are going to race down a twisting mountain road, and Neely stands between the two cars and starts the race, and we wonder if anyone associated with this film possibly saw “Rebel Without a Cause.”

What’s interesting is the way the director, Justin Lin, surrounds his gaijin with details of Japanese life, instead of simply using Tokyo as an exotic location. We meet the sumo wrestler, who will be an eye-opener for teenagers self-conscious about their weight. We see pachinko parlors, we see those little “motel rooms” the size of a large dog carrier, and we learn a little about the Yakuza (the Japanese Mafia) because D. K.’s uncle is the Yakuza boss Kamata (Sonny Chiba). One nice touch happens during the race on the mountain road, which the kids are able to follow because of instant streaming video on their cell phones.

Lin, still only 33, made an immediate impression with his 2002 Sundance hit “Better Luck Tomorrow,” a satiric and coldly intelligent movie about rich Asian-American kids growing up in Orange County and winning Ivy League scholarships while becoming successful criminals. That movie suggested Lin had the resources to be a great director, but since then he’s chosen mainstream commercial projects. Maybe he wants to establish himself before returning to more personal work. His “Annapolis” (2006) was a sometimes incomprehensible series of off-the-shelf situations (why, during the war in Iraq, make a military academy movie about boxing?).

But in “The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift,” he takes an established franchise and makes it surprisingly fresh and intriguing. The movie is not exactly “Shogun” when it comes to the subject of an American in Japan (nor, on the other hand, is it “Lost in Translation“). But it’s more observant than we expect, and uses its Japanese locations to make the story about something more than fast cars. Lin is a skillful director, able to keep the story moving, although he needs one piece of advice. It was Chekhov, I believe, who said when you bring a gun onstage in the first act, it has to be fired in the third. Chekhov might also have agreed that when you bring Nathalie Kelley onstage in the first act, by the third act the hero should at least have been able to kiss her.