“The Evening Star” is a completely unconvincing sequel to “Terms of Endearment” (1983). It tells the story of the later years of Aurora Greenway (Shirley MacLaine), but fails to find much in them worth making a movie about. It shows every evidence, however, of having closely scrutinized the earlier film for the secret of its success. The best scenes in “Terms” involved the death of Aurora’s daughter, Emma, unforgettably played by Debra Winger. Therefore, “The Evening Star” has no less than three deaths. You know you’re in trouble when the most upbeat scene in a comedy is the scattering of the ashes.

The movie takes place in Houston, where Aurora lives with her loyal housekeeper Rosie (Marion Ross) and grapples unsuccessfully with the debris of her attempts to raise her late daughter’s children. The oldest boy (George Newbern) is in prison on his third drug possession charge. The middle boy (Mackenzie Astin) is shacked up with a girlfriend and their baby. The girl, Melanie (Juliette Lewis) lives with Aurora, but is on the brink of moving in with her boyfriend, a would-be actor. (The absence of their father, Flap, played in the first movie by Jeff Daniels, is handled with brief dialogue.) Aurora has broken up with the General (Donald Moffat), who lives down the street, but he is still a daily caller, drinking coffee in the kitchen with Rosie and offering advice. Next door, in the house that used to be owned by the astronaut (Jack Nicholson), is now the genial Arthur (the late Ben Johnson), who also pays Rosie a great deal of attention. And still on the scene is Patsy (Melanie Richardson), Emma’s best friend and now one of Aurora’s confidants.

All of these people live together in the manner of 1950s sitcoms, which means they constantly walk in and out of one another’s houses, and throw up the windows to carry on conversations with people in the yard. I don’t know about you, but if I had to live in a neighborhood where all of my friends and neighbors were hanging out in the kitchen drinking my coffee and offering free advice and one-liners all day, I’d move. Let them go to Starbucks.

Rosie, a lovable busybody, notices that Aurora has fallen into a depression and tricks her into seeing a therapist, Jerry (Bill Paxton). Aurora tells him that she is still seeking “the great love of my life.” Anyone who has slept with an astronaut played by Jack Nicholson and can still make that statement is a true optimist. Soon, amazingly, the much-younger Jerry violates all the rules of his profession and asks her out, and we get one of those patented movie scenes designed to show how a rich older lady is the salt of the earth: She takes him to a barbecue joint named the Pig Stand, where she knows everybody by name (this is probably one of the danger signals of alcoholism).

Now we’re in for a series of scenes showing how colorful Aurora is, and sure enough, before long she actually crawls in through Jerry’s window. The explanation for Jerry’s fascination with her, when it finally arrives, is no less inane for being predictable. (I dislike most movie scenes where new characters are dragged onscreen for one shot, just to provide a punch line.) More developments: Melanie, the granddaughter, wants to move to L.A. with her boyfriend, Bruce. Rosie and old Arthur start dating. The General gets into a snit because Aurora is dating Jerry. Rosie decides to marry Arthur (“Nobody else has ever told me they loved me. Besides, I’ll just be next door.”). When Rosie gets sick, Aurora reveals her credentials as a control freak by going into Arthur’s house and carrying Rosie back to her own house, in the rain.

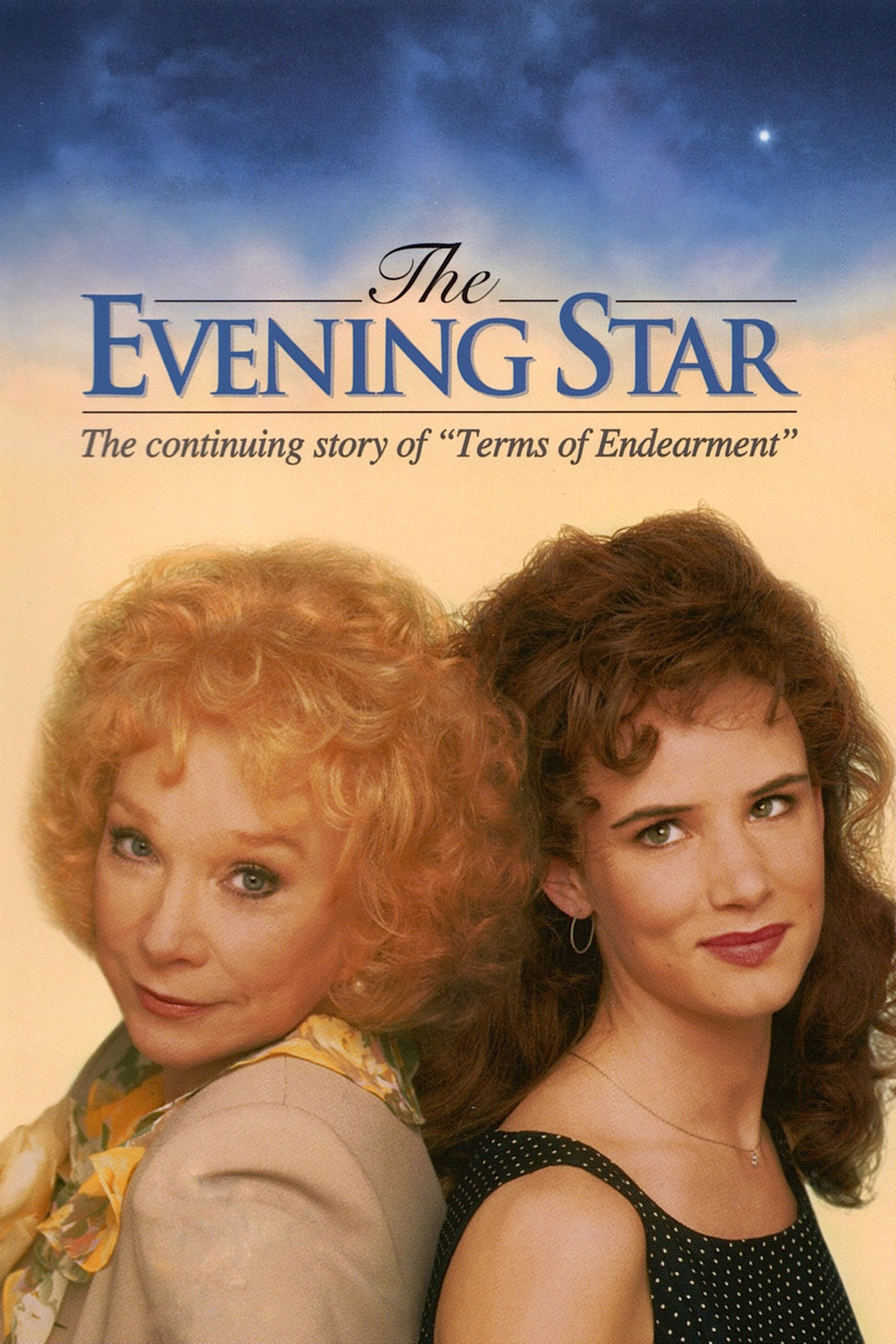

As a counterpoint to these events, Aurora rummages in a closet and comes up with a roomful of diaries, photo albums, old dance cards, theater programs and journals, which collectively suggest set decorators and prop consultants are on an unlimited budget. And the astronaut (Nicholson) turns up again, briefly, adding a shot in the arm. “I’m still looking for my true love,” Aurora tells him, and he replies, with the movie’s best line, “There aren’t that many shopping days until Christmas.” “Terms of Endearment” was about a difficult relationship between two strong-willed women, the MacLaine and Winger characters. Juliette Lewis, as the granddaughter, is available for similar material here, and indeed her performance is the most convincing in the movie, but the script marginalizes her, preferring instead a series of Auntie Mame-like celebrations of Aurora, alternating with elegiac speeches and clunky sentiment.

Sequels are a chancy business at best, but “The Evening Star” is thin and contrived. Even the music has no confidence: William Ross’ score underlines every emotion with big nudges, and ends scenes with tidy little flourishes. The title perhaps comes from “Crossing the Bar,” by Tennyson, who wrote: Sunset and evening star, And one clear call for me! And let there be no moaning of the bar, When I put out to sea . . .

His bar, of course, was made of sand, and is not to be confused with the Pig Stand. In “The Evening Star,” however, there is a great deal of moaning when anyone puts out to sea.