If you have a good idea, a strong cast, a smart script, and directorial chops, you don’t need a lot of money to make a compelling movie. “The Endless” is proof. Overseen by the filmmaking team of Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead—who specialize in brainy meta-horror, and who star as brothers who decide to revisit the UFO cult where they grew up—this is a movie that plays with our perceptions of time, space, and reality, and sketches the outlines of unimaginable terror while leaving the details to our imagination.

Like much of the cast, Benson and Moorhead play characters who share the performers’ real-life first names—a common indie filmmaking affectation that wouldn’t raise an eyebrow if this were a drama, but that adds one more layer of oddness in a science-fiction film. Justin is the older brother, Aaron the younger. They grew up in a compound in a hilly stretch of forest somewhere in Southern California (the movie was shot near San Diego). The story begins with Justin and Aaron living an anonymous life as regular citizens. The opening scenes reveal that Justin “rescued” Aaron and took both of them out of the cult. Then Aaron watches a videotaped message from a once-fellow cult member, Callie Hernandez’s Anna, and realizes he misses the place even though he knows it was bad for him. He tells Justin that he wants to go back for “closure.” Justin thinks this is a bad idea but agrees, out of love for his brother and because, on some deep level, he misses it, too.

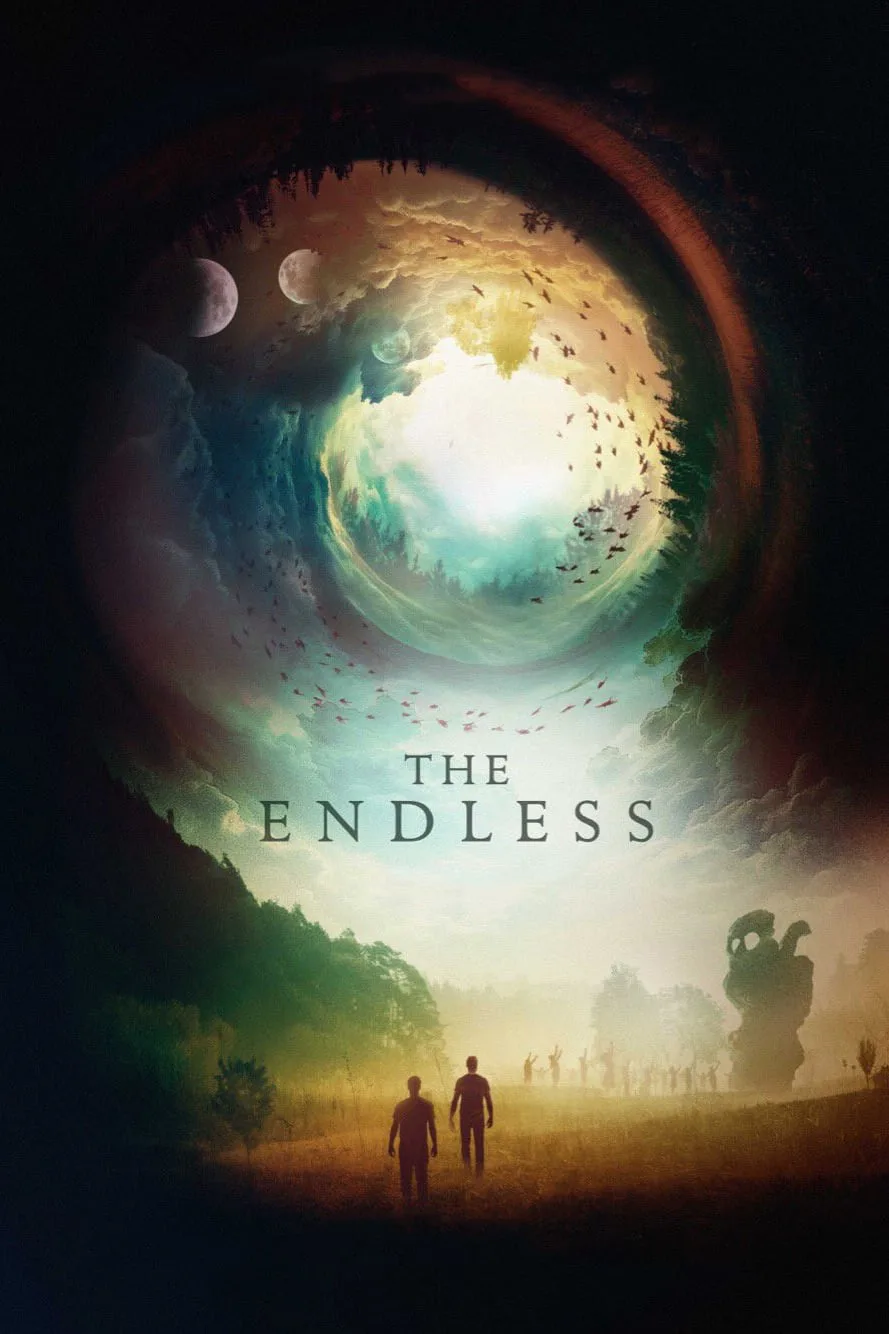

Things get weird before the brothers even reach the compound, thanks to an atmosphere of mystery and menace realized with clever sound design, a synthesized score (by James Lavelle) that samples “House of the Rising Sun” and evokes the best of John Carpenter; and unexplained images that recur. This story is filled with circles, and circles within circles. Or maybe we should call them “saucer shapes.” There’s an overcast sky with a hole punched through the clouds; round wind chimes clinking in in the breeze; wooden benches arranged around a campfire. Circles are embedded into the score itself: “House of the Rising Sun” is built around a series of circular chord patterns, and the lyrics are about a gambler’s son who escaped an abusive childhood but seems determined to repeat his father’s sins by choice. Mirrors are as important, too. There are actual mirrors in the film, mirrored compositions, characters whose fates or personalities seem to mirror each other, and moments where the universe seems to tear a hole in itself and show us what’s on the other side.

Things become unmoored from scientifically verifiable truth. We enter the psychic terrain of horror films that make us doubt our perceptions. There are so many strange moments and images, most of them tossed-off, that if you list them all without context, as I’m doing here, it sounds as if your brain is fragmenting. Which, of course, is the point of telling the story as Benson and Moorehead tell it: form follows function here, and the subject is the way cult brainwashing and isolation combine to destroy the ability to distinguish fantasy from reality.

Characters keep taking trips of various distances (anywhere from hundreds of miles to a few feet) only to end up where they started. Sometimes they experience and re-experience the same events from the same angle, or a slightly different angle. Do they have free will, or did their psychological conditioning by the cult turn that into one more illusion, like the strange images they encounter around the camp? Do they make choices, or do choices make them? The cult prides itself on having no leader, but is this true? There’s a quiet, reactive fellow named Tim (Lew Temple) who has a bushy red beard, long red hair, an angular face, and the authoritative demeanor of a tribal chief. He’s pictured standing beside the door of a shack that’s been sealed with a huge, 19th-century looking padlock: nobody ever goes in there. There are throwaway lines about how particular characters in the film are a lot older than Aaron and Justin, even though they’re played by actors their age or slightly younger.

I’m being vague about the plot on purpose, because it’s ultimately not the main focus of “The Endless,” and because so much of the film’s effectiveness comes from comparing what we’re told would happen against what actually does happen (or what appears to happen). The circular visual motifs and circular (or repetitive) plotting evokes films that examine karma, evolution, free will and destiny by confronting their characters with variations of the same challenges over and over again: think of “Edge of Tomorrow,” “Groundhog Day” and “Looper.”

The film seems to be set sometime before or immediately after the dawn of the 21st century, judging from the video technology and flip phones and apparent lack of Internet access, but we can’t be sure. As the movie goes on, even older technology starts to appear, some of it so visibly filthy or damaged (or so divorced from necessary accessory tech, such as as batteries or cords) that there’s no way it could work; but of course it does work, conveying messages that seem generated by malevolent forces. A simple card trick that Justin smugly sees through gives way to a trick involving a baseball, so impervious to rational explanation that it chills the blood. And let’s not get into the trip the brothers take in a rowboat, or the uncanny events that seem to occur whenever Justin goes running.

All of the lead performances are superb. The best are probably Moorhead; Benson; Hernandez; Kira Powell as the kind of glassy-eyed kook that Shelly Duvall used to specialize in; and James Jordan as a Dennis Hopper-like babbling lunatic named Shitty Carl. But it’s hard to choose. Everybody’s giving their all here. And the blatantly “big” performance moments are balanced out by numerous, just-right grace notes, such as the teasing, familiar, brotherly way that Justin and Aaron talk to each other, and the zonked-out, practically affectless way Powell’s character corrects Justin, telling her that a meth-head hermit she just described to him wasn’t a boyfriend, but “just this guy I was sort of obsessed with, when I was on lithium, Thorazine and PCP.”

The filmmaking is mostly restrained and intelligent, strategically framing characters, moving the camera to reveal or conceal information, and amping up tension with surprising edits, dissonant sound effects, and Lavelle’s music, which is so unsettling that I would not be surprised to learn that it was performed on a keyboard made from frayed human nerve endings. Not every moment in the film works: the lead actors overdo it a bit during the opening section, which unfortunately showcases some terrible, exposition-dump dialogue, and the CGI is dodgy in a way that’s characteristic of moviemakers whose artistic ambitions exceed their budgets.

But it’s ultimately the suggestions, implications and shock effects that put the story over the top, as well as the emphasis on the characters’ neuroses and longings. What these brothers are ultimately searching for is a place to call home. It doesn’t matter to them if it’s a cult compound full of deluded, psychologically destructive manipulators or some sort of intergalactic prison, torture compound or zoo (or whatever this place is), as long as they know their way around, and are surrounded by faces they recognize. The camp is their House of the Rising Sun. These two have one foot on the platform, the other on a train, and they’ve gone back to the compound to swing that ball and chain.