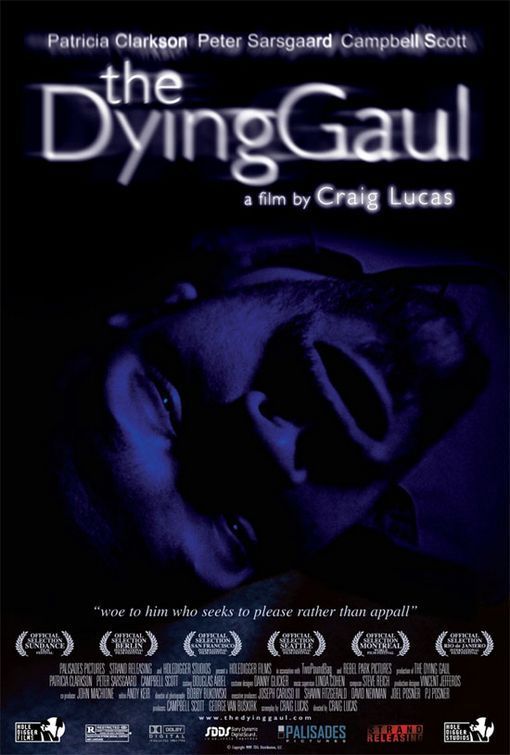

“Woe to him who seeks to please rather than to appall.”

Those words appear onscreen in the first shot of “The Dying Gaul.” Here is another quotation, from later in the film: “No one goes to the movies to have a bad time. Or to learn anything.” The first quotation is from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. The second is by a Hollywood studio executive, about a screenplay he likes but thinks is not commercial. The screenplay is about a homosexual love affair. Make the lovers heterosexual, the executive tells the writer, and I’ll cut you a check for $1 million, here and now.

The executive is Jeffrey, played by Campbell Scott, who is becoming a master of characters with controlled but alarming emotions. The screenwriter is Robert, played by Peter Sarsgaard, in a sincere and inward role a little unusual for him. His screenplay is about his former lover, who was also his agent.

“Americans hate gays,” Jeffrey tells him flatly. Then he dangles temptation before Robert, who is broke and has child support to pay.

“Who do you think should direct this?”

“Gun Van Sant,” says Robert, “since Truffaut is dead.”

“Would you like me to show it to him?”

“Yes.”

“That’s good, because I already have.”

This dialogue, by the writer-director Craig Lucas, depends on us to realize that Jeffrey has not shown the screenplay to Gus Van Sant, and probably never will. The opening stages in a movie negotiation are like a romance, with the screenwriter as the blushing bride and the producer as the prince who strews riches at his feet. Just compromise this one time, Jeffrey tells Robert, and soon, like Spike Lee, you’ll be making your own films in your own way.

“The Dying Gaul” grabs us immediately with this seduction by negotiation. It follows with scenes establishing another Hollywood convention: If you’re doing business with someone, you are immediately “family.” Robert is invited to Jeffrey’s home, and introduced to his wife Elaine (Patricia Clarkson) and their children. Elaine likes his mind. On the other hand, Jeffrey likes Robert’s body. “Let’s hug,” he tells Jeffrey at one point in their negotiations. Everybody hugs in Hollywood. It is a good way to look someone in the eye while stabbing them in the back. “You are very handsome,” Jeffrey says in mid-hug. “And I’m getting a little turned on. Are you?”

Robert caves in and makes his story about heterosexuals at about the same time he and Jeffrey start having sex. It takes Robert less than 10 seconds on the computer to find “Maurice” and replace it with “Maggie.” Neither one of them observes that Maurice is the name of a novel about a gay man that E. M. Forster did not allow to be published until after his death. No doubt other rewriting will take out AIDS and substitute cancer. “It’s going to be a beautiful movie,” Jeffrey promises him.

At this point in “The Dying Gaul” I could see no way the movie could step wrong, but it does. The movie is based on Craig Lucas’ play, and represents his directorial debut. His previous screenplays include “Longtime Companion” (1990), with its Oscar-nominated performance by Bruce Davison as the companion of a dying AIDS victim, and “The Secret Lives of Dentists” (2002), which also starred Campbell Scott and was about secrets and possessiveness in a marriage.

“The Dying Gaul” considers some of this same material, but adds a dimension that is at first intriguing and then, I think, fatal. The troublesome device is an Internet chat room. Elaine, a former screenwriter who now has time and loneliness on her hands, likes Robert immediately. They gossip. He confesses that with his lover dead, his sex life is conducted mostly online. Robert says the chat rooms are like “life after death,” with disembodied voices floating in the ether. Elaine asks, “What’s your favorite really dirty chat room?”

Before he answers, I should issue a spoiler warning. I will not reveal crucial details, but I will describe a few things you may prefer not to know. The movie proceeds with parallel affairs, one real, one virtual. Jeffrey and Robert become lovers, while Elaine creates a fictional identity in Jeffrey’s chat room, and is soon one of Jeffrey’s regular correspondents. What she writes and what he thinks and what the result is, I will leave for you to discover. It is all done well enough. I object for two more fundamental reasons: (1) There is no reason to believe Robert particularly believes in the supernatural, and (2) Would it not occur to Robert that he had, after all, told Elaine about his favorite chat room? He has a bulb that needs to be changed, the one right above his head.

So there are implausibilities in the plot devices that lead the movie to its ultimate conclusion. And then the final developments themselves, I think, are wrong in both theory and practice. There is some ambiguity about why a final event takes place, and that’s all right, but the way in which the movie reveals it is, I think, singularly ineffective. It leads to one of those endings where you sit there wishing they’d tried a little harder to think up something better.

It’s all the more depressing because the performances are effective, especially the way Clarkson obliquely approaches the crisis in her marriage. And I liked the way Scott’s character insists on being both gay and straight. There’s a Hollywood producer for you: Greedy.