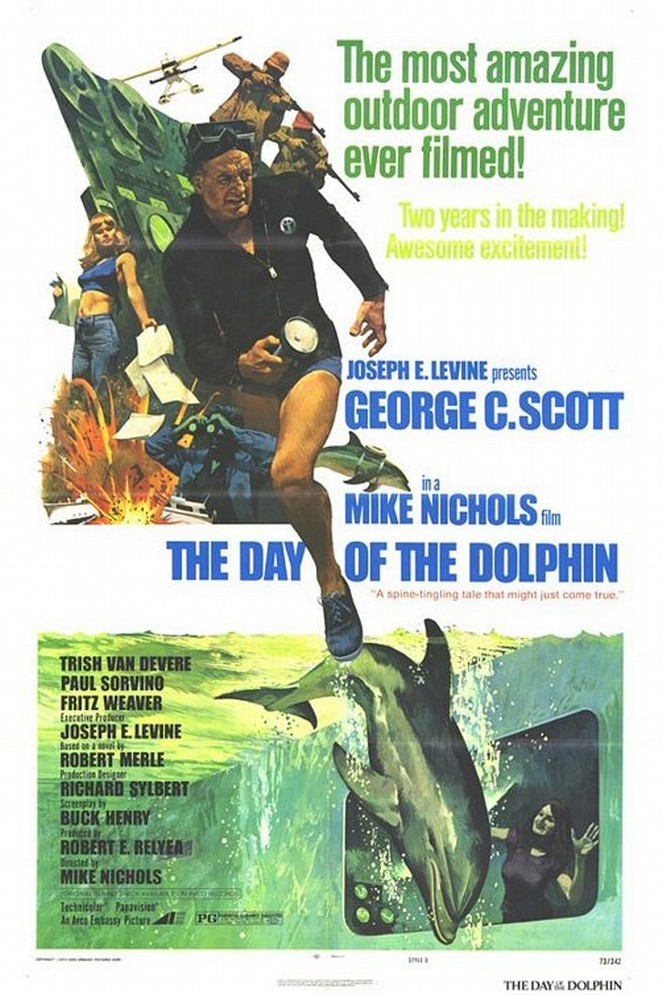

Mike Nichols’ “The Day of the Dolphin” trips on its own stylishness and tries so hard not to be a conventional science-fiction thriller that it fails, alas, to be anything.

The same material might have been more interesting in the hands of a less ambitious director, who could have gone for suspense, action and laughs. Instead, Nichols gives us a vast gray moral middle ground, on which the various U.S. intelligence agencies vaguely clash. The original novel by Robert Merle, a left-radical Frenchman, was more exciting than this. He gave us a secret task force that had succeeded in communicating with dolphins, and then there was lots of intrigue as attempts were made to kidnap (dolphinap?) the prize specimens. They were to be used as undetectable carriers of underwater mines, as highly intelligent swimming H-bombs and as the agents of assassination against people living on boats. At the end of the novel, if memory serves, a nuclear war is about to break out and the heroes are being towed toward Cuba by the prize dolphins.

This sounds like fairly silly material, but Merle got away with it by (a) communicating a great deal of accurate and interesting information about dolphins so that his plot even seemed plausible) (b) inventing a weary prose style in which the amoral activities of U.S. spies seemed to personify the Cold War, and (c) giving us lots of sexual intrigues and jealous office politics around the laboratory. He also went into his characters’ minds and made them more interesting, as people, then they needed to be as elements of the plot.

Nichols and his screenwriter, Buck Henry, apparently decided that a closing shot of George C. Scott and Trish Van Devere heading out to sea would be dangerously funny. So the movie stops far short of Merle’s fantasies.

What happens is that Scott and his team train an especially intelligent dolphin, Alpha, and then give him a mate. Just as the mate is about to learn to talks, both dolphins are snatched by the members of some sort of underground organization.

I say “some sort” because I don’t know which sort. They are, in any event, on the other side of the fence from the SPY who joins forces with Scott.

“Who are they?” he says at one point. “They’re the guys who are paid by their guys to watch our guys, who are paid to watch them.” If I didn’t get the explanation quite right, no matter. Anyway, that bad guy’s scheme is to use one of the dolphins to place a large explosive mine under the presidential yacht. This part of the movie has a nice twist to it, sort of a shaggy-dolphin story. Nichols is so shy about using his material to entertain that he starts with an illustrated lecture at a woman’s club (as did Merle) and then takes most of an hour to even admit a plot is afoot. Ordinary B-movie exposition would have been more effective. It’s a nuisance to have to listen to everybody dropping weighted nuances and not knowing what they’re talking about.

Against these purely dramatic shortcomings, I guess we ought to balance the movie’s really superb treatment of dolphins. After seeing the real dolphins in the movie obey on command (and, most of the time, in unfakable single takes), I was just about able to believe they’ll be replacing our Polaris fleet in a couple of years. There’s a marvelous scene in which Scott, in Scuba gear, frolics with a wildly affectionate Alpha, and the dolphins are so believable as, uh, people, that at the movie’s final tearful parting, we’re almost moved. Almost, but that’s better than laughing out loud during the tearjerker scenes in “Jonathan Livingston Throwup,” or whatever it was. George C. Scott is fine as the head of the task force; he hasn’t seemed able to give an uninteresting performance in recent years.

Trish Van Devere, his wife in real life, as well as in the movie, also is good, but she has another one of those soupy women’s roles that infect so many recent movies. Why can’t we have a woman who’s intelligent, quick-witted and capable, for once? Even as a marine biologist, for heaven’s sake, she has to do all the dumb things like get bit by Alpha and break into tears at the end. Female marine biologists are just dumb dames with degrees, right? The movie finally just sort of lays there. If it had gone all out in a single direction – if it had tried to simply be an interesting movie about dolphins, or a self-confessed espionage thriller – it might have worked.

But Nichols apparently took the project too seriously; the last thing we really needed was a “Day of the Dolphin” that aims to be, of all things, dignified and bittersweet.