The happiest people I come into contact with seem to be those who have real jobs. In the last few weeks, I’ve talked with a Macintosh tutor, a doctor, a set designer, a stagehand, a heating and air-conditioning man, a lawyer, a Web designer, my editor, an animator and Millie Salmon, the woman who is my caregiver, although that job description makes me sound more decrepit than I am.

All of these people work hard, know what they’re doing, think it’s worth doing, enjoy it and take pride in it. There is the same serenity I sensed from my father, who was an electrician and a damned good one. I do not, however, pick up good feelings from those people I know who are largely involved in “making money for the stockholders.” They focus on moving money around, hiring and firing, cutting costs, serving the bottom line. They are caregivers for corporations, which would be more satisfactory if corporations were not essentially balance sheets. I know the Supreme Court has ruled that corporations are individuals, but when did one ever tell you a good joke?

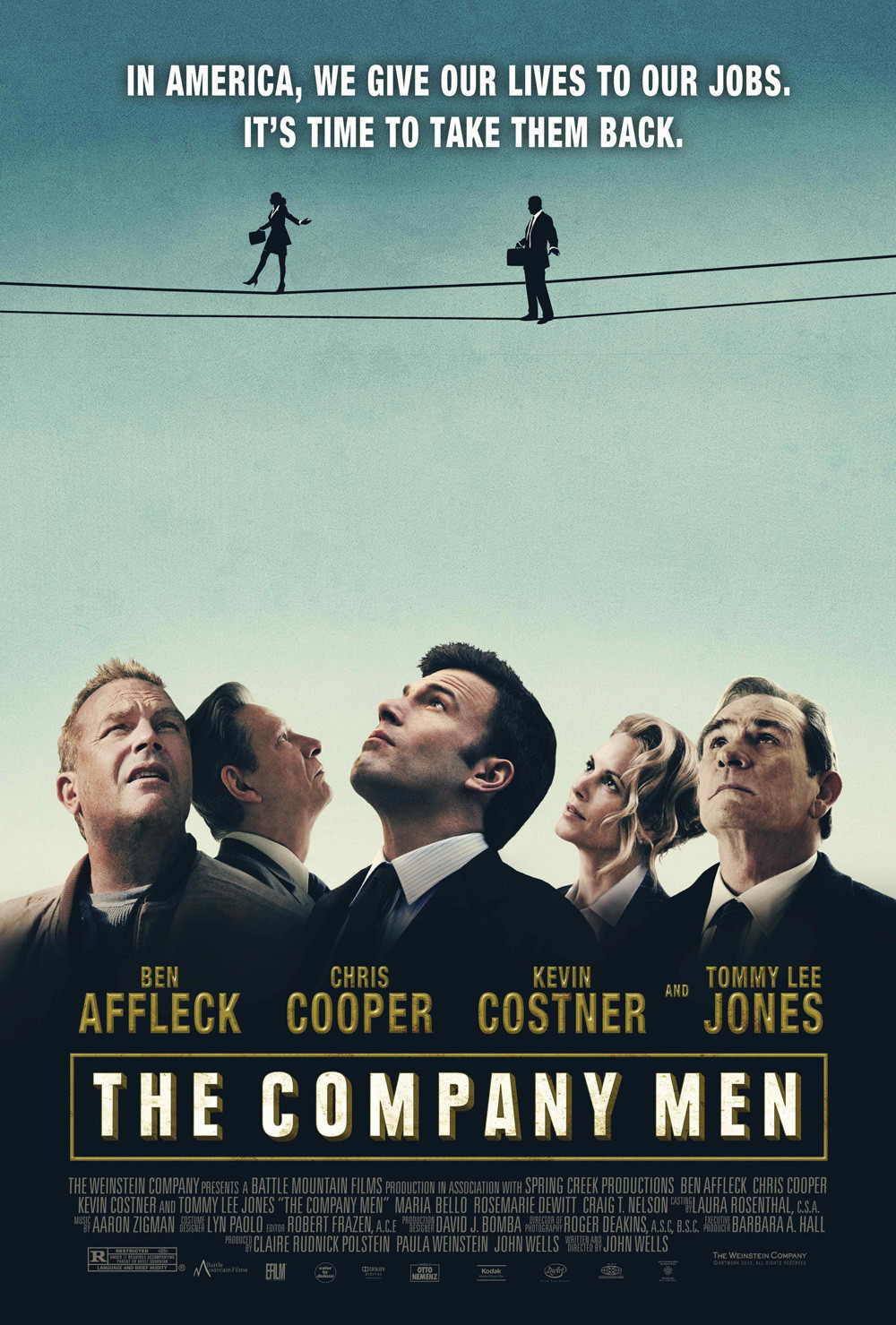

“The Company Men” follows the stories of characters who have oriented their lives around a corporation once named General Transportation Systems. Years ago, this company involved two men who began building ships; small ones at first, and then big ones. Now it’s called GTX, which is how we spell Acme these days. Caught in the economic downturn, GTX is downsizing, and some of its employees are discovering their primary occupation was making and spending a lot of money, and that without those jobs, there isn’t much they really know how to do.

We focus at first on Bobby Walker (Ben Affleck), who drives a Porsche and has a nice golf handicap, a big suburban house and a wife named Maggie (Rosemarie DeWitt), who is an expert consumer. Bobby loses his job. His severance and “savings cushion” can’t support his overhead. He enters, with great displeasure, the shadow world of the unemployed. His company has paid for temporary office space at a job search center that helps him with his resume. He attends group therapy sessions where he learns how to present himself and think positively. He loathes them.

Phil Woodward (Chris Cooper), an older man at GTX, is also fired. If there is no great demand for Bobby, there is none for an unemployed executive around 60. He was literally his job. Without it, in economic terms, he is a man with no buyers and nothing to sell. He was under the impression he had importance and value. He realizes that was a fiction. Employees of corporations are like free-ranging scavenger cells. When the corporation inhales in good times, they find themselves in a warm place with good nurture. When it exhales in bad times, they go spinning into the vast, indifferent world.

GTX was started by Salinger (Craig T. Nelson) and McClary (Tommy Lee Jones). McClary preserves the belief that a corporation owes its employees some loyalty, and that it should serve a useful function. Salinger has outgrown that phase and realizes a corporation survives only by maximizing its profits and producing one primary product: income. As Salinger’s vision prevails over McClary’s old-fashioned idealism, the inexorable task of “working for the shareholder” is reduced to “sacrificing the jobs and lives of others for the bottom line.”

Although the actors are convincing and the film well-crafted, “The Company Men” delivers few satisfactory character portraits because the movie isn’t really about characters, it’s about economic units. When a corporation fires you, it doesn’t much care whether you’re a good friend, a loving father, a louse or a liar. You are an investment it carries on its books, or not. The movie’s impact comes when these people realize it doesn’t matter in economic terms who they are.

There’s one character who really does something. This is Jack Dolan (Kevin Costner), Bobby’s brother-in-law, who owns a small construction company that builds one house at a time. He and his workers know how to make house siding lie true, how to use materials efficiently, how to — well, how to drive a nail. Bobby has always dismissed Jack as a “working man,” but when you’re out of work that looks pretty good.

Written and directed by John Wells, “The Company Men” offers no great elation or despair. Its world is what it is. We all live in it. In good times, young people go to the movies and dream of becoming Gordon Gekko. In bad times, a house builder looks more like a Master of the Universe. It happens I’ve been talking with a few young people who are trying to make career decisions. My advice involves the old cliche, “Find what you really love doing and make that your profession.” I think this is true. If you have to be unemployed, it might seem less bleak if you hated doing the job, anyway.