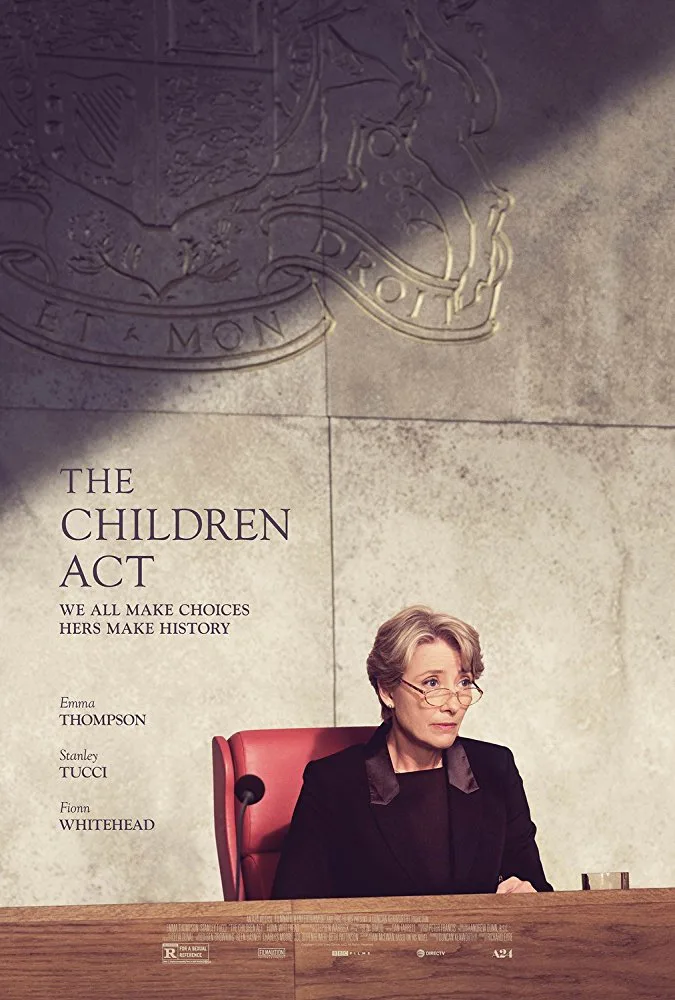

Graceful dramas for adults are a scarcity these days. But thanks in part to a reliable supply of Ian McEwan adaptations, like the excellent but frustratingly under-the-radar Spring 2018 release “On Chesil Beach” (Dominic Cooke), we are luckily treated to some refreshingly grown-up material featuring complex humans at life-defining crossroads, forced to make choices that directly clash with the set of beliefs they had thus far lived by. Sophisticated and challenging, “The Children Act” continues this trend for filmgoers who would like to flex their intellectual muscles and engage with serious themes that don’t revolve around crudeness or kids in masks and spandex. Adapted by McEwan from his own novel and bolstered by an expressive performance by Emma Thompson (astounding even by her consistently high standards), “The Children Act” is perhaps a bit stilted in the overt way it sometimes attempts to spell out its arguments. But director Richard Eyre’s film still poses sophisticated questions around family, religion, marriage, law and the delicate boundaries that can or cannot be crossed in each institution.

Referred to as “My Lady” by almost everyone around her (as it should also be the case in real life, in all honesty), Thompson leads us into the film’s elaborate themes straightaway through her character Judge Fiona May. In the opening moments, Fiona is about to rule a much-publicized case about twins conjoined at birth—surgically separating the twins will cause one of them to pass away, and leaving them be means the death of both. While the logical decision seems obvious—why not give one of them the chance to survive and thrive—the religious parents of the twins disagree with interfering with what they call God’s will and committing a surgical act they consider to be murder. Naturally, Fiona rules the case in accordance with the law and the Parliament’s The Children Act, which puts logic over personal beliefs.

At her upscale, tastefully decorated London flat complete with a Baby Grand Fazioli piano (on which she frequently plays Bach), things don’t seem any easier than they are in the courtroom. Her neglected husband Jack (Stanley Tucci) casually complains about their now sexless marriage and announces his desire to have an affair with a younger member of his faculty, without paying the slightest bit of attention to the constant life-or-death pressure Fiona seems to be under in her chosen field. Soon enough, another one of those extreme cases presents itself; one centered on the 17-year-old Adam (the terrific Fionn Whitehead of “Dunkirk”), who needs an urgent blood transfusion to survive his battle with leukemia. Having been raised by a Jehovah’s Witness family who views mixing another person’s blood in their son’s body as toxic and morally wrong, Adam firmly mirrors his parents’ beliefs and declines the procedure, accepting his fate. Yet still being a minor mere weeks away from his 18th birthday, the decision would really be up to Fiona—she visits Adam, an impressive kid of great potential and sense of humor, at his hospital bed, eventually ruling to save the kid’s life.

Overwhelmed by the new possibilities of life, the now spiritually whole but religiously doubting Adam grows an infatuation towards Fiona; writes her profound letters and follows her around while she deals with her growing set of problems at home, intensified by the high-pressure rehearsals for an upcoming concert. Thompson excels through these emotionally demanding scenes, burying her reserved character’s softer side and true feelings for Adam deep within and safely out of sight, while she acts in the only logical way she knows how. Eyre grabs on to an impossible balance here, founded between subtle sexual tension and protective instincts—he smartly shies away from exploiting either end of the spectrum. Admittedly, Adam’s verbal pleas to Fiona feel a bit labored and overwrought—but they still come across as plausible in the hands of a young boy visibly infatuated by a powerful woman who saved his life. Meanwhile, McEwan doesn’t entirely abandon Jack, either. His selfish demands assume a complex dimension in the midst of a modern-day marriage challenged by relatable issues: what happens when careers, priorities and the once intense but now subdued desires eventually interfere in the bedroom? As mature as movies get, the elegantly costumed and designed “The Children Act” is a welcome getaway from the now-fading summer’s loud fare, into something quiet and tasteful that aims for the aging soul.