There is an unpleasant way in which “The Chamber” and the previous John Grisham thriller, “A Time to Kill,” linger over the racism and hate language of their characters. Yes, the racist characters are the villains. But the ugly things they say linger in the air, there to be admired by anyone on their wavelength.

Any subject, including racism, can be the legitimate material of a movie. But I am not happy when I see deep wounds in our society being opened for the purpose of entertainment. “The Chamber” is not a serious movie about anything, and so when characters are allowed to rant at length about their hatred of African Americans and Jews, repeating the most vile hate clichés, what I get from the screen is not simply dialogue but the broadcasting of dangerous language.

Sometimes racially charged language plays a defensible role, as it did in Martin Scorsese’s “Casino,” a thoughtful film that dealt with the tension between gangsters of Italian and Jewish descent. But in the two Grisham films this year, I get the queasy feeling that race hate is working like a condiment to add spice to otherwise unremarkable courtroom stories. That’s particularly true because the villains in each film (played by Kiefer Sutherland in “A Time to Kill” and Gene Hackman and Raymond Barry in “The Chamber”) are the most colorful characters, overwhelming the more pedestrian heroes played by Matthew McConaughey and Chris O'Donnell.

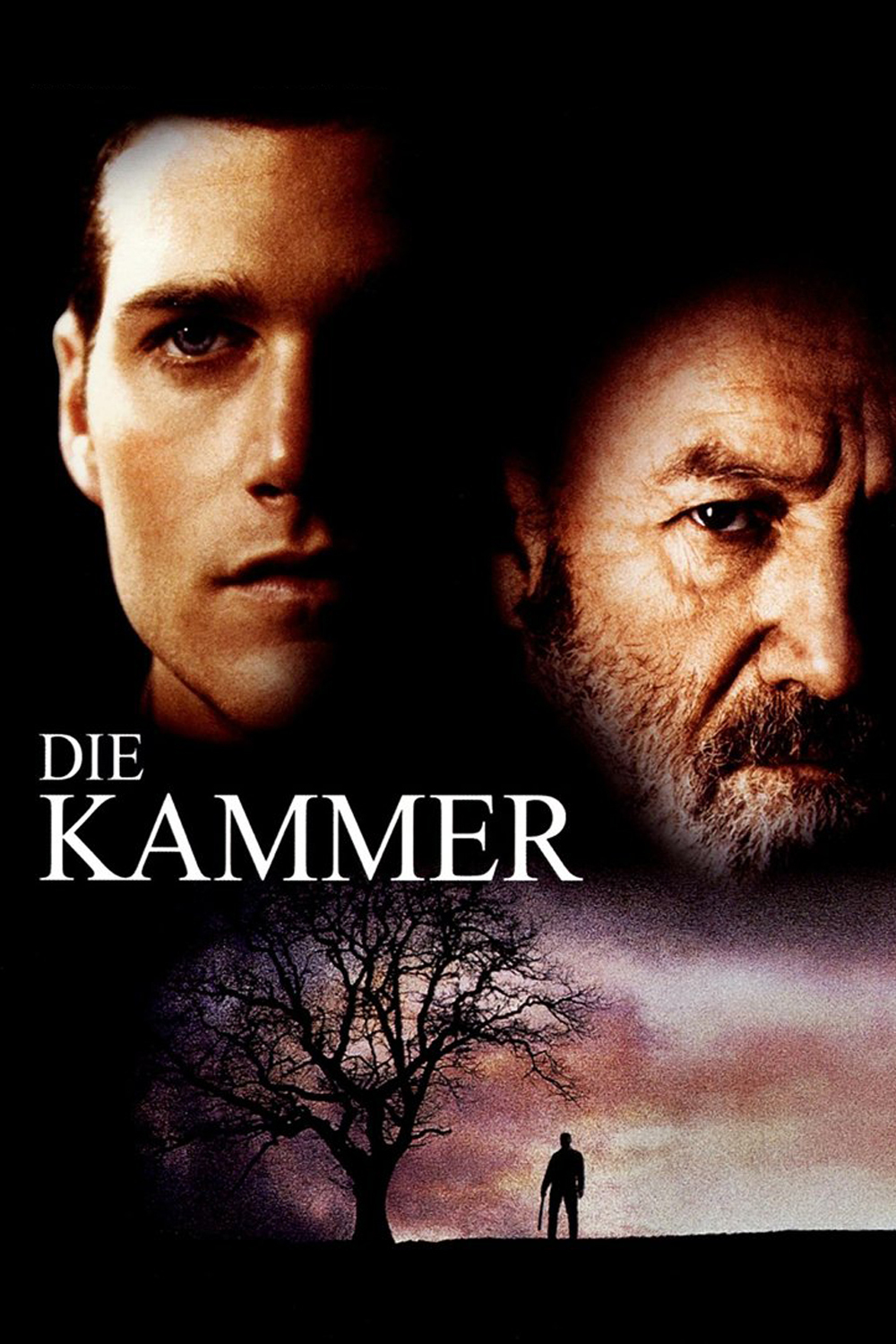

“The Chamber” tells the story of a young Chicago lawyer named Adam Hall (O’Donnell) who wants to go down South to handle the final appeal of a murderer on Death Row. The killer, a Klan member named Cayhall (Hackman), has been convicted of setting off a bomb in the offices of a Jewish civil rights attorney. The attorney’s two young sons were killed; he was maimed and later committed suicide. What the movie reveals fairly quickly is that Adam Hall is Cayhall’s grandson. Adam’s father also committed suicide–perhaps because of the violent acts he watched Cayhall perform.

The murders took place in the 1960s. Appeals have dragged on for years, but now the time of execution is near. Adam goes south and discovers old family secrets from his aunt (Faye Dunaway), who watched years ago as Cayhall shot gunned a neighboring black man to death. Cayhall quickly discovers who his new attorney really is, and reacts with a litany of colorful hate language.

I have heard all of Cayhall’s clichés before, but they have pretty much disappeared from general use in America, and there will be some younger audience members hearing them for the first time. How will these words affect them? In both “A Time to Kill” and “The Chamber,” the Ku Klux Klan, with its secret meetings and ghostly costumes, is presented in a way that is technically negative but could seem thrilling. The films portray the Klan as criminal, racist and anonymous, but those have always been its selling points; it is not portrayed as boring and stupid.

The real subject of “The Chamber” is the family left behind by old Sam Cayhall: his son, a suicide; his grandson, who dreams of a Death Row miracle; his daughter (Dunaway), who has married a local banker and says she’s “done pretty well for poor white trash. But when the world finds out I’m Hitler’s daughter . . .” Flashbacks show how Cayhall murdered the father of his son’s black playmate, traumatizing his children and sending remorse spiraling down through the generations.

Because Cayhall is played by Gene Hackman, an actor who implies decency in his very bones, we know that he will not go to the gas chamber spouting Klan slogans. If the film’s purpose had been to present an unredeemable villain, they would have cast Christopher Walken, Dennis Hopper, M. Emmet Walsh or another actor who can be read as completely hateful. Hackman is a superb actor, but even in his most vile moments here, the musical score undermines the effect by sneaking in feelings of sadness and thoughtfulness. Listen carefully when the grandson tells Cayhall about a fake bomb in his motel room; the music playing under Cayhall’s reaction gives away the ending.

O’Donnell is sincere and focused as the lawyer, but he is really too young to bring much more to the role. Since he hates racism, why does he want to defend his grandfather? Because he hates the death penalty more? Or because he hopes for a deathbed conversion? The movie’s own attitudes toward the death penalty are confused; Hackman brilliantly delivers a long monologue describing the effect of poison gas on the system, but then the movie suggests some people may deserve that very effect.

There is also some confusion involving Cayhall’s relationship with another conspirator named Rollie Wedge (Raymond Barry). Without giving away details, all I can suggest is that Cayhall’s loyalty serves the plot, not common sense. And, given the fact that Cayhall has spent years in prison mouthing the language of the Klan, it is inexplicable that the movie has a scene in which he quietly nods a sad farewell to his black fellow inmates on Death Row. I didn’t believe his behavior, and I particularly didn’t believe theirs.

In the early days of X-rated movies, they were always careful to include something of “redeeming social significance” to justify their erotic content. Watching “The Chamber,” I was reminded of that time. The attitudes about African Americans and Jews here represent the pornography of hate, and although the movie ends by punishing evil, I got the sinking feeling that, just as with the old sex films, by the time the ending came around, some members of the audience had already gotten what they bought their tickets for.