Robert Schwentke is a German-born director with what appear to be two distinct artistic identities. In the United States, where he works most of the time, he is an ultra-contemporary technician who started off with an affinity for the disgusting genre exercise (see 2002’s “Tattoo,” in which a serial killer skins their victims, for the ink) but then expanded his horizons to find employment adding sheen to all manner of second-tier franchise trefe, including two installments of the “Divergent” trilogy.

The other Schwentke doesn’t work as frequently, but goes back to Germany to do so. 2003’s “The Family Jewels” was a very black comedy about a guy who becomes occupied with retrieving his cancerous testicle, removed in surgery, from a hospital. (Apparently it’s somewhat autobiographical.) And this film, which was screened at the Toronto Film Festival last year (and praised by this site’s Tina Hassannia there), is darker still, and beautifully made.

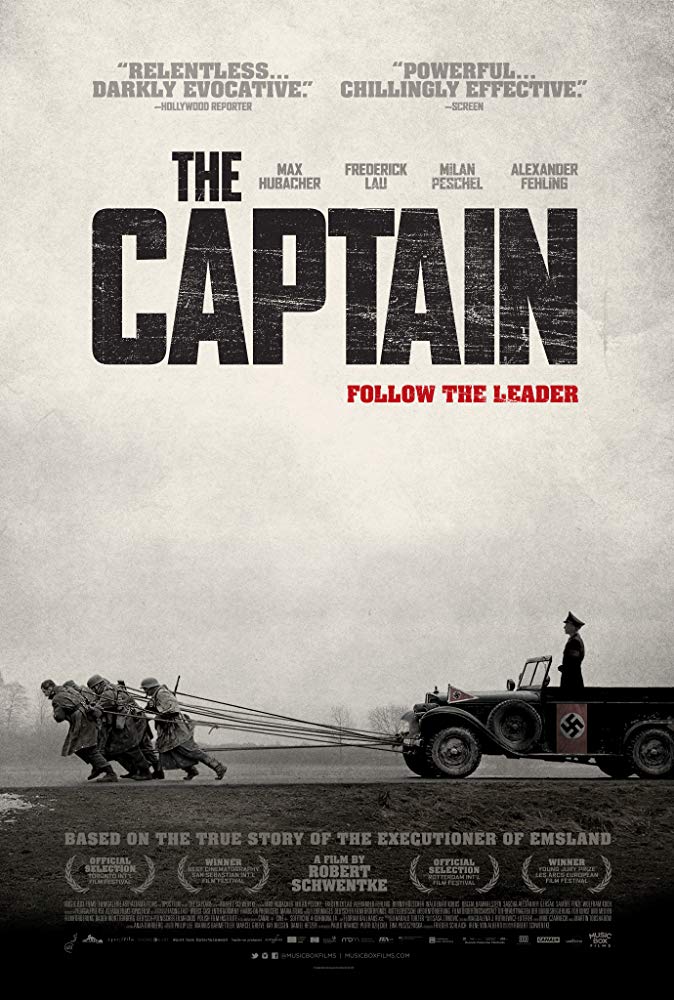

Outlandish as its action often is, “The Captain” is based on a true story. Schwentke’s film, though, has an allegorical/satirical axe to grind, and it more often than not frames the narrative in dark archetypal terms. It begins, in tonally rich black-and-white, with a desperate bedraggled soldier fleeing on foot as a jeep pursues him. The fellows in the jeep taunt the man on foot, calling him “piggy” and such. You have to feel for the fellow. Is he a deserter? Disobedient? Title cards have told us it’s two weeks before the end of the war in Europe, so you can infer that discipline might be a little dicey with some German troops.

The fellow gets away and then becomes a hunter-gatherer, with little success. He barely escapes getting shot by irate farm owners keeping a close eye on their chickens. In a little while he finds a jeep, and in it, the uniform and some of the equipment of an army captain. Complete with an imposing little monocle. These will certainly come in handy.

“The Captain” is based on the real-life story of Willi Herold, who was separated from his regiment during the German army’s retreat back to its home company and, upon assuming the identity of a captain, came upon a prison camp where he ordered the execution of more than 100 inmates.

Schwentke intends a parable of how even the smallest, perhaps especially the smallest, people can rise to the occasion when suddenly given authoritarian power to wield. Willi is played with remarkable conviction by Max Hubacher, who constricts his face into a rat-like vision of first fear, then murderous smugness. Willi can use his captain’s guise to wallow in whatever luxuries might be available to him in these last days of war, and eventually he does, but mainly he’s interested in throwing his new-found weight around in the most awful ways possible.

Schwentke has, I infer, watched a good number of Soviet World War II films, including those of Larisa Sheptiko and Andrei German. His camera really gets into the mud even as his stylization becomes increasingly infused with tricks he learned in Hollywood (late in the movie, one character is subjected to a full-body explosion). As much integrity as “The Captain” has, it’s also subject to some glibness. The movie seems at times a little too pleased with itself and its mordant observations on humanity, which reach their apogee in the film’s coda, which lets Hubacher, in full costume as Willi, loose in the Germany of today.