Those con-man movies are best that con the audience. We should think at some point that everything is for real, or even better, that we can see through it when we can’t. I offer as examples works by the master of the genre, David Mamet: “House of Games,” “The Spanish Prisoner” and “Redbelt.”

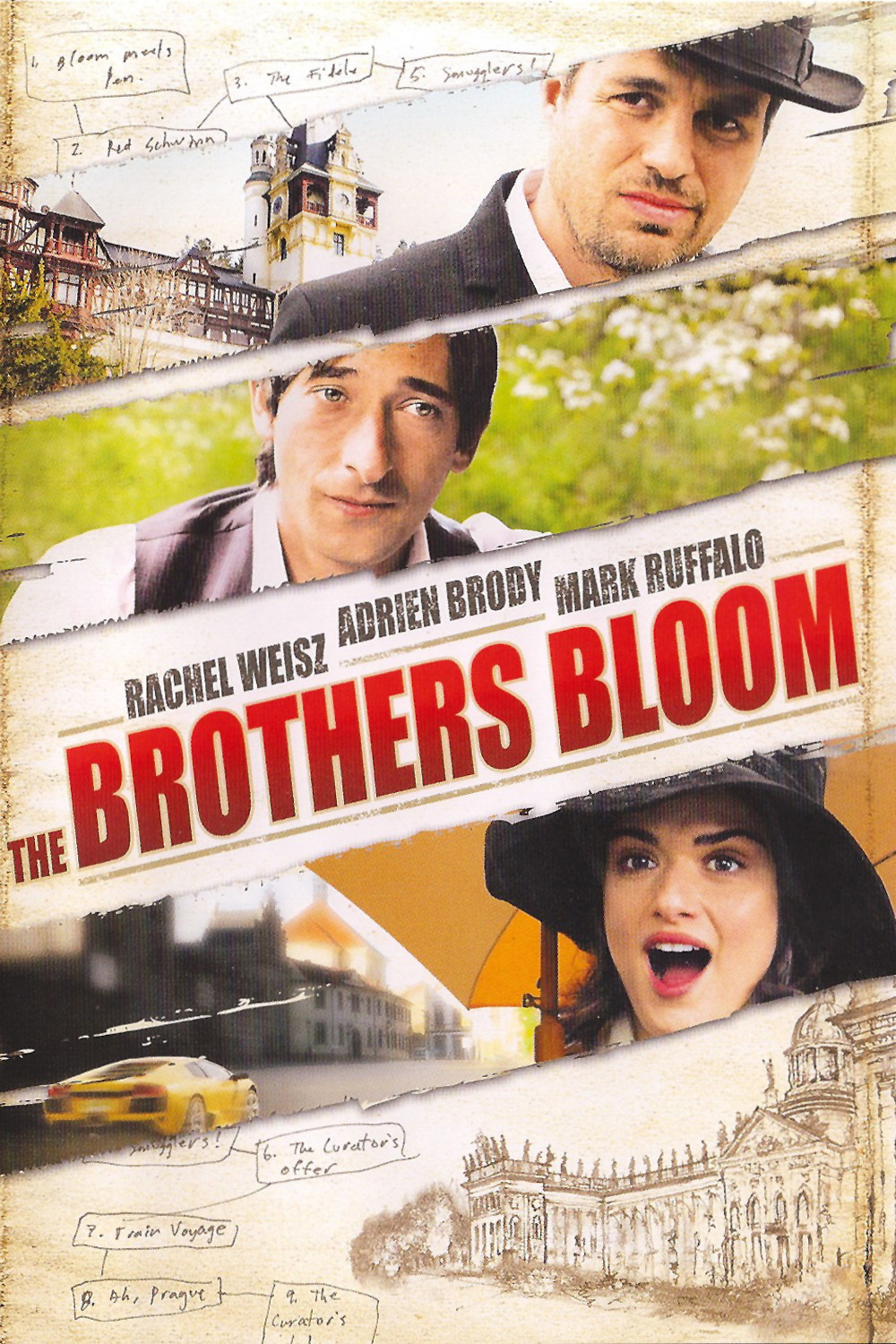

Rian Johnson‘s “The Brothers Bloom” lets us in on the con and then fools us. It does that in an interesting way. It gives us Stephen (Mark Ruffalo) and Bloom (Adrien Brody), and I might as well get this out of the way: I don’t know why they’re called the brothers Bloom when that’s the first name of one, and neither seems to have a family name. Maybe I missed something.

From childhood, Stephen has fabricated con scenarios and created the characters and scripts for his younger brother Bloom to join him in. When they’re adults, Stephen’s girlfriend Bang Bang (Rinko Kikuchi), who speaks extremely rarely, is mostly involved as a passive bystander, witness, validator or sometimes more. For Stephen, life is a con, and he’s living it. For Bloom, the game is getting old.

They meet a promising mark named Penelope (Rachel Weisz), who is rich, beautiful and lonely, even though most women who are rich and beautiful don’t have a crushing problem with loneliness. She falls into a scheme fashioned by the brothers, and I will not specify which falls in love with her, but one does, and then … I have to watch my step here. The brothers are such perfectionists that they like to involve as many marks as they can. Let’s leave it that.

At a certain point, we think we’re in on the moves of the con, and then we think we’re not, and then we’re not sure, and then we’re wrong, and then we’re right, and then we’re wrong again, and we’re entertained up to another certain point, and then we vote with Bloom: The game gets old. Or is it Stephen who finds that out? Bloom complains, “I’m tired of living a scripted life.” We’re tired on his behalf. And on our own.

The problem with the movie is that the cons have too many encores and curtain calls. We tire of being (rhymes with perked) off. When an exercise seems to continue for its own sake, it should sense it has lost its audience, take a bow and sit down. And even then “The Brothers Bloom” has another twist that might actually be moving, if we weren’t by this time so paranoid. As George Burns once said, “Sincerity is everything. If you can fake that, you’ve got it made.” A splendid statement, and I know it applies to this movie, but I’m not quite sure how.

This a period picture, but a little hazy as to which period. It’s the second feature by the 35-year-old Rian Johnson, who made the acclaimed Sundance “originality” winner “Brick” in 2005. That was a film-noir crime story transplanted to a California high school. Now we have “The Sting” visiting Eastern Europe. “The Brothers Bloom” was filmed for a reported $20 million, which is chicken feed if you consider the locations in Montenegro, Serbia, Romania and the Czech Republic.

The acting is a delight. Rachel Weisz creates a New Jersey heiress who is painfully lonely — strange, for such a beauty — and delightfully ditzy. Ruffalo is sincere at all times, even when he’s not. Brody is so smooth his logical contradictions slide right past: He makes them sound as if they must mean something. And the enigmatic Bang Bang, who never says a word, but often seems as if she’s about to. And Johnson wisely hired Mamet vet Ricky Jay, to provide a narration that suggests a lot more than he’s telling.

Johnson has a fertile imagination, a way with sly comedy and a yearning for the fantastical. But he needs to tend to his nuts and bolts and meat and potatoes. The film is just too smug and pleased with itself; as a general rule, an exercise in style needs to persuade us it cares about more than style. Lesson in point: “The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou.” This movie is lively at times, it’s lovely to look at, and the actors are persuasive in very difficult material. But around and around it goes, and where it stops, nobody by that point much cares.