Tarantino we recognize because of the way his dialogue, like Mark Twain’s, unfurls down the corridors of long, inventive progressions, collecting proper names and trademarks along the way, to arrive at preposterous generalizations–delivered flatly, as if they were the simple truth.

Mamet is even easier to recognize. His characters often speak as if they’re wary of the world, afraid of being misquoted, reluctant to say what’s on their minds: As a protective shield, they fall into precise legalisms, invoking old sayings as if they’re magic charms. Often they punctuate their dialogue with four-letter words, but in “The Spanish Prisoner” there is not a single obscenity, and we picture Mamet with a proud grin on his face, collecting his very first PG rating.

The movie does not take place in Spain and has no prisoners. The title refers to a classic con game. Mamet, whose favorite game is poker, loves films where the characters negotiate a thicket of lies. “The Spanish Prisoner” resembles Alfred Hitchcock in the way that everything takes place in full view, on sunny beaches and in brightly lit rooms, with attractive people smilingly pulling the rug out from under the hero and revealing the abyss.

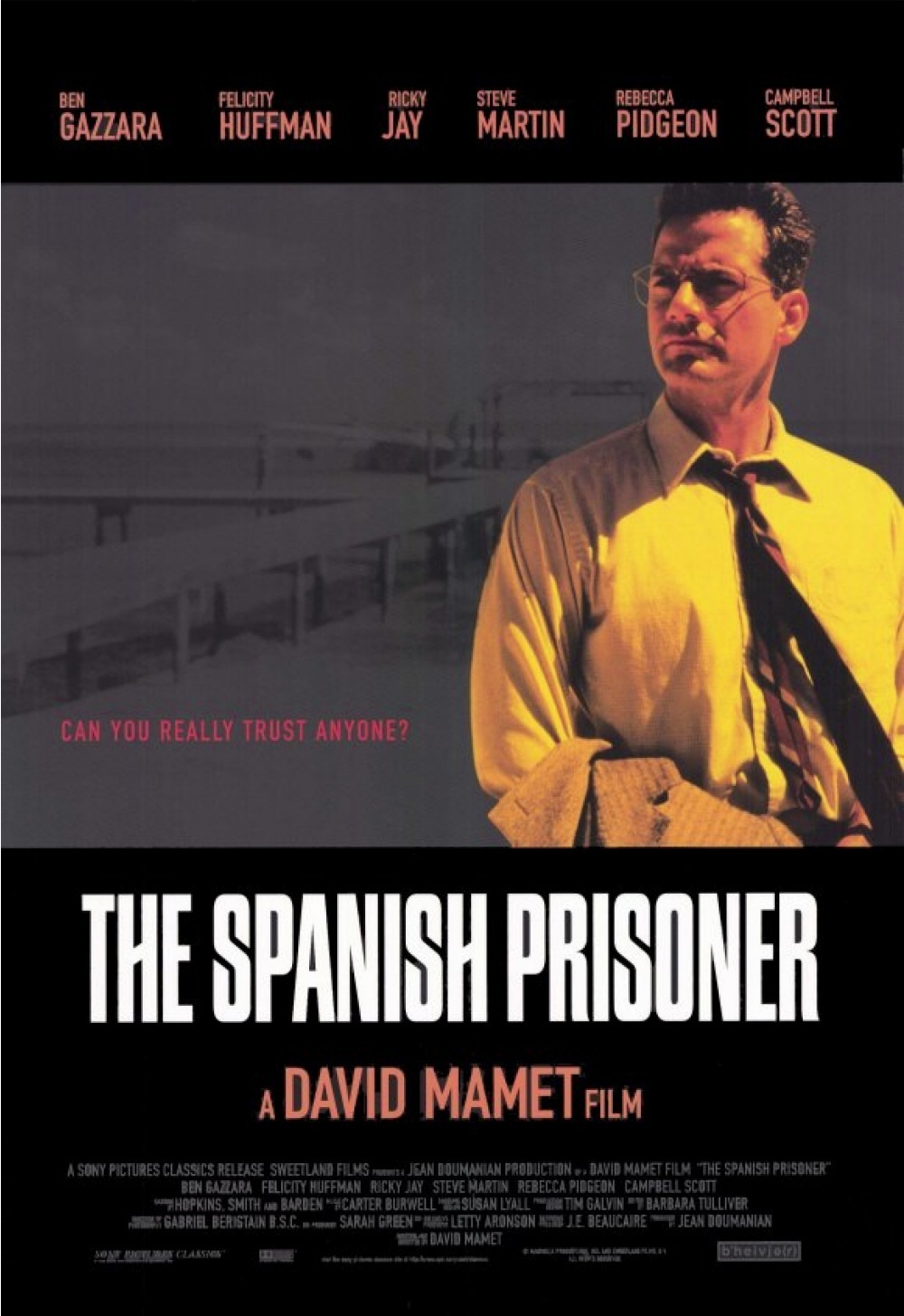

The hero is Joe Ross (Campbell Scott), who has invented a Process that will make so much money for his company that when he writes the figure on a blackboard, we don’t even see it, only the shining eyes of executives looking at it. (“The Process,” he says. Pause. “And by means of the Process, to control the world market.” The missing words are replaced by greed.) He works for Mr. Klein (Ben Gazzara), who has convened a meeting in the Caribbean to discuss the Process. Also on hand is George, a company lawyer played by Ricky Jay–a professional magician and expert in charlatans, who is Mamet’s friend and collaborator. And there is Susan (Rebecca Pidgeon, Mamet’s wife), whose heart is all aflutter for Joe Ross, and who is very smart and likes to prove it by saying smart things that end on a triumphant note, as if she expects a gold star on her report card. (“I’m a problem solver, and I have a heart of gold.”) To the Caribbean island comes a man named Jimmy Dell (Steve Martin), who may or may not have arrived by seaplane. We see how Mamet creates uncertainty: Joe thinks the man arrived by seaplane, but Susan thinks he didn’t, and provides photographic proof (which, as far as we can see, proves nothing), and in the end it doesn’t matter if he arrives by seaplane or not; the whole episode is used simply to introduce the idea that Jimmy Dell may not be what he seems.

He seems to be a rich, friendly New Yorker, who is trying to conceal an affair with a partner’s wife. He says he has a sister in New York, and gives Joe a book to deliver to her (“Might I ask you a service?”). Joe has thus accepted a wrapped package from a stranger that he plans to take on board a plane; you see how our minds start working, spotting conspiracies everywhere. But at this point the plot summary must end, before the surprises begin. I can only say that anything as valuable as the Process would be a target for industrial espionage, and that when enough millions of dollars are involved, few people are above temptation.

“The Spanish Prisoner” is delightful in the way a great card manipulator is delightful. It rolls its sleeves above its elbows to show it has no hidden cards, and then produces them out of thin air. It has the buried structure of a card manipulator’s spiel, in which a “story” is told about the cards, and they are given personalities and motives, even though they are only cards. Our attention is misdirected–we are human, and invest our interest in the human motives attributed to the cards, and forget to watch closely to see where they are going and how they are being handled. Same thing with the characters in “The Spanish Prisoner.” They are all given motives–romance, greed, pride, friendship, curiosity–and all of these motives are inventions and misdirections; the magician cuts the deck, and the joker wins.

There is, I think, a hole in the end of the story big enough to drive a ferryboat through, but then again there’s another way of looking at the whole thing that would account for that, if the con were exactly the reverse of what we’re left believing. Not that it matters. The end of a magic trick is never the most interesting part; the setup is more fun, because we can test ourselves against the magician, who will certainly fool us. We like to be fooled. It’s like being tickled. We say “Stop! Stop!” and don’t mean it.