`I’m 28 years old and all I’m good at is being gay,” complains Marshall (Justin Theroux), one of the gay friends who hang out together in “The Broken Hearts Club.” To cheer himself up, he should rent “The Boys in the Band” (1970), and find out how much better gay men are at being gay than they used to be.

The new movie acts like a progress report; instead of angst, Freudian analysis, despair and self-hate, the new generation sounds like the cast of a sitcom, trading laugh lines and fuzzy truisms. The earlier movie half-suggested it was impossible to be gay and happy. That possibility would not occur to the “Broken Hearts” characters.

The movie takes place in the predominantly gay area of West Hollywood, where its heroes hang out in coffee shops, restaurants, clubs and each other’s homes. Most of the principals are not sleeping with each another, although some are, and others are not sleeping with anyone. Mostly they talk, and the movie listens. What it discovers is that gay men, like straight men, spend an extraordinary amount of time thinking about sex. And that they can be insecure, unfaithful, lonely and deceptive (when an actor recycles lines from an audition to make a touching breakup speech, his ex asks, “Are you reading that off of your hand?”).

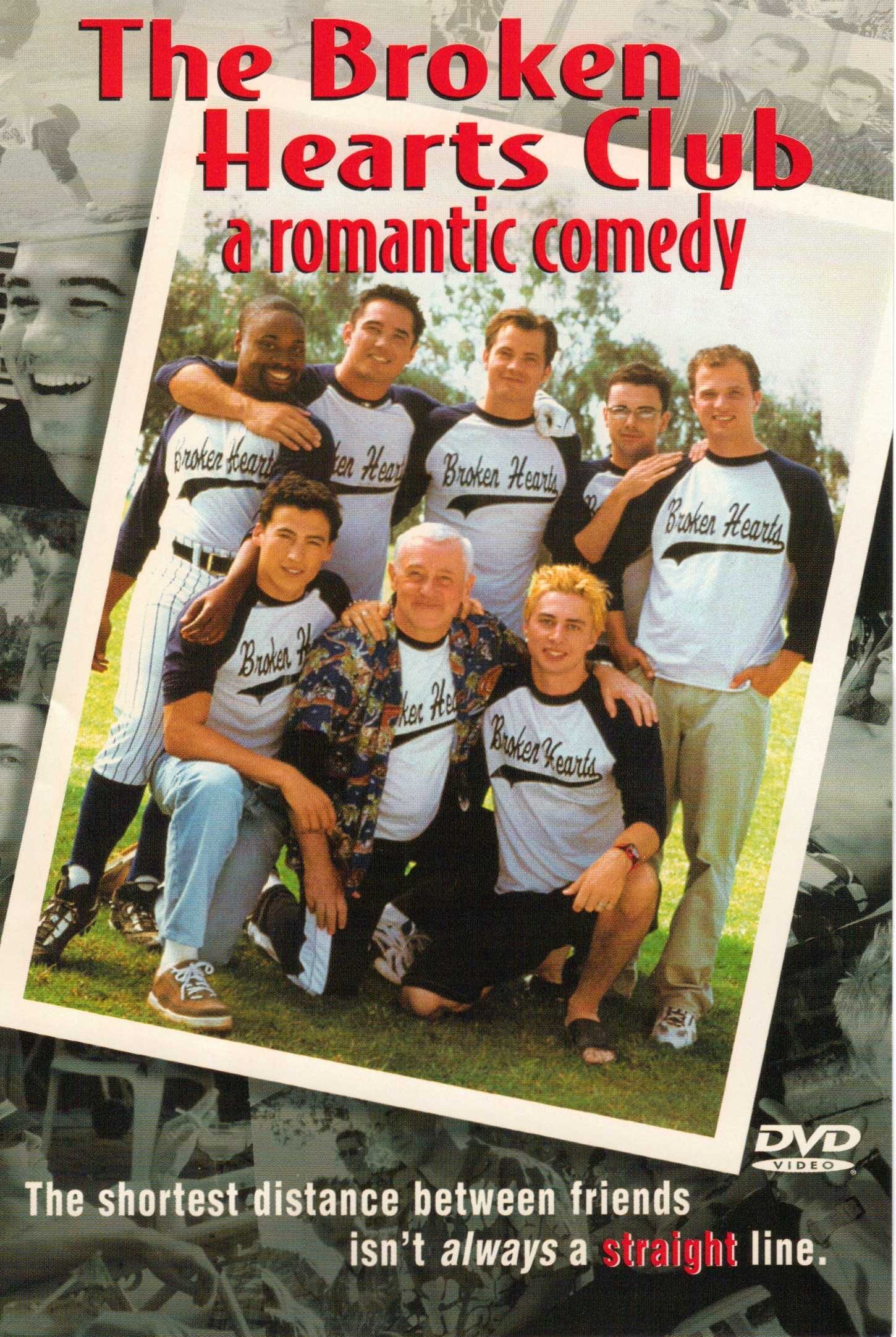

Life centers on the Broken Hearts, a restaurant run by the fatherly Jack (John Mahoney), who also sponsors a softball team. Many of the characters are members of the team, and there’s a funny scene where the handsome Cole (Dean Cain, from “Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman”) steps up to the plate and gets the phone number of the opposing catcher between strikes. Mostly, though, dates don’t come that easily, and Patrick (Ben Weber) complains, “Gay men in L.A. are 10s looking for an 11. On a good night, and if the other guy’s drunk enough, I’m a six.” What’s striking about the movie is the ordinariness of its characters and what they talk about. This is a rare gay-themed movie that relaxes. Historically, many movies about gays have had a buried level of, I dunno, call it muted hysteria, anxiety, impending doom. It’s the “Kiss of the Spider Woman” syndrome, with characters dramatizing what they see as their own current or impending tragedies. “The Broken Hearts Club” is not about neurosis, resentment, AIDS or secrecy, and the humor can be described as sarcastic rather than bitchy. The big difference between this picture and your regular guy movie is that there aren’t any girls (except for a lesbian sister and her lover). There are no complaints about parents. One guy says his mother was a ’60s love child: “In high school, she caught me smoking pot and all she said was, `I hope you didn’t pay market.’ ” The lighthearted tone is set right at the beginning, as a group of friends plays a game to see who can act the straightest the longest before one reveals an OGT (Obviously Gay Trait). We are introduced to the definition of “meanwhile,” which is a word introduced into any conversation when an interesting sex object walks by. One of the characters lands a date with a handsome J. Crew model, then drops him because he doesn’t like the Carpenters. There’s a debate: “Who would you kick out of bed? Morley Safer or Mike Wallace?” This is exactly the way straight guys talk, except they substitute Cameron Diaz and Jennifer Lopez. (Answer: “I’d kick them both out of bed for Ed Bradley, circa 1980.”) All of course is not banter. There’s tension between Patrick and Leslie (Nia Long), the girlfriend of his sister (Mary McCormack). There’s bitterness about “gym bunnies,” and their obsessions with “sex and protein shakes.” There are moments of truth, involving a romance threatened by roving eye syndrome, and the movie is so eager to get to an obligatory funeral scene that we can diagnose the doomed character almost from his entrance. The writer-director, Greg Berlanti, one of the creators of “Dawson’s Creek,” has mastered his screenplay workshops and knows just when to introduce the false crisis, the false dawn, the real crisis and the real dawn.

But the movie is so likable, we go with it on its chosen level. It’s almost the point of “The Broken Hearts Club” that it doesn’t crank up the emotion. It insists on the ordinariness of its characters, on their everyday problems, on the relaxed and chatty ways they pass their time. The movie’s buried message celebrates the arrival of gays into the mainstream. That key line (“I’m 28 years old and all I’m good at is being gay”) is like an announcement liberating gay movies from an exclusive preoccupation with sexuality. “The Broken Hearts Club” is good at things other than being a gay movie. There you are.