“The Blind Swordsman: Zatoichi” embodies the kinds of contradictory elements that make Takeshi Kitano Japan’s most intriguing contemporary actor-director. He plays, as usual, a man with an impassive face, few words, and sudden bursts of action that end in a few seconds. He is vastly amused at private jokes. He has a code, but enforces it according to his own rules. And then there is the style of the movie, and what only can be called its musical numbers.

Kitano, who acts under the name Beat Takeshi, has played mostly modern tough guys, but here he ventures back to the 19th century to step into the shoes of Zatoichi, a blind swordsman who was the hero in one of the two most popular movies series in Japanese history. Zatoichi was always played by Shintaro Katsu, who appeared in 26 of these films before his death in 1989. (Toro-San, a sort of Japanese Jerry Lewis, was played by Kiyoshi Atsumi in no less than 48 films between 1969 and 1995.)

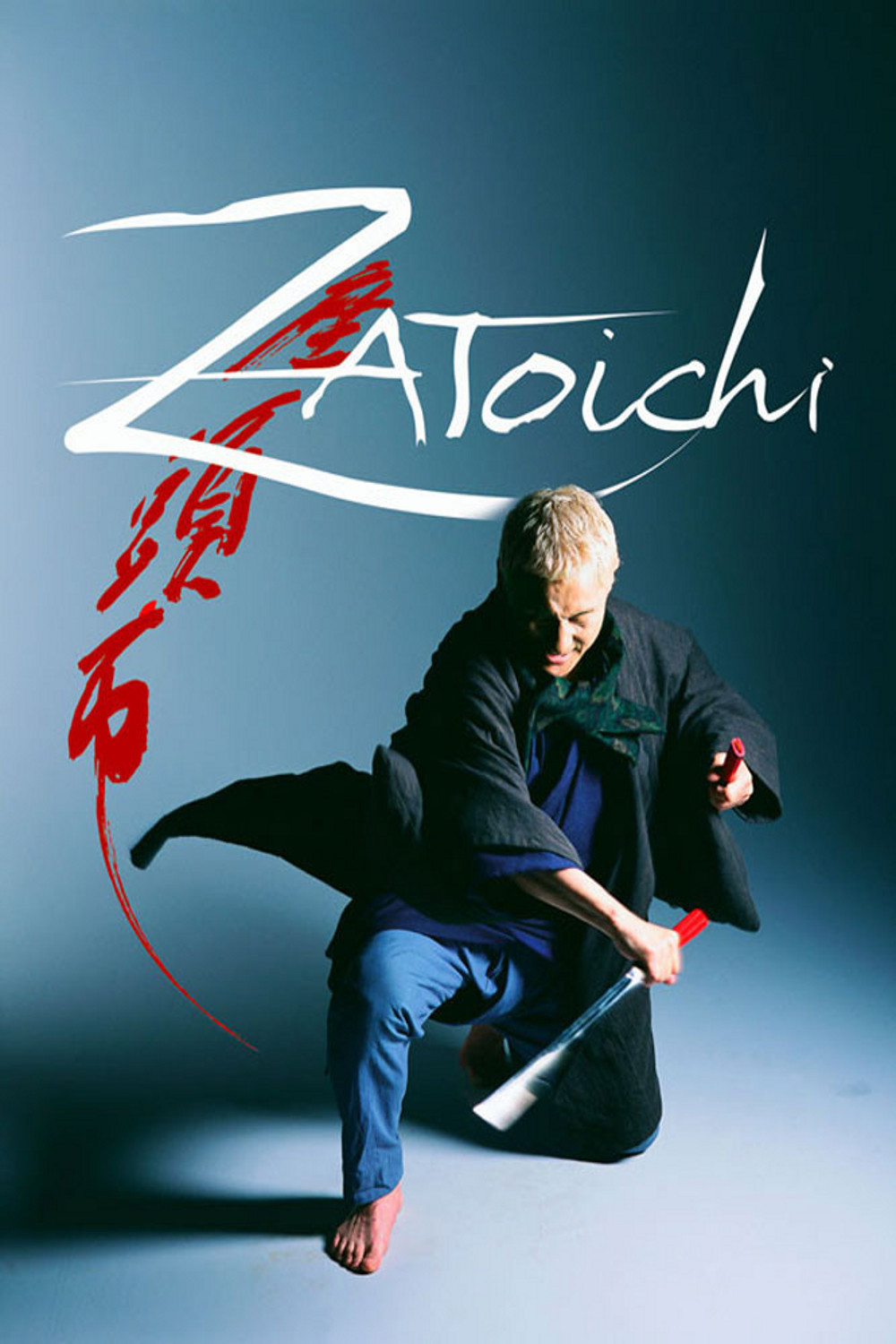

Kitano playing Zatoichi is a little like Clint Eastwood playing Hopalong Cassidy; the star brings along a powerful persona that redefines the pop superficiality of his character. He poses as a humble wandering blind masseur whose hearing and instinct are so razor-sharp that he knows better what is going on around him than those who are limited to sight. He walks with a slight stoop, sometimes smiles or laughs to himself, carries his head cocked to one side, never seems tense or coiled, and then in an instant his cane-sword has found its target.

In its broadest outlines, “Zatoichi” is a revenge drama. The blind swordsman encounters on his travels two sisters (one actually a transvestite) who work as geishas at a wayside rest station. They were orphaned when their parents were killed by the merciless Ginzo gang, which shakes down small merchants. Zatoichi learns about their story, and although he never declares his intention to do anything, eventually the gang’s retainers begin to die while trying to kill him. Finally all comes down to a duel between Zatoichi and the crime boss’ high-priced bodyguard Hattori (Tadanobu Asano), a warrior of fierce talents.

This plot, however conventional it may sound, plays quite differently in Kitano’s hands because of his acute and distinctive style of pace and timing. Not for him the 10-minute Hong Kong-style martial arts extravaganzas. In one scene set in a stony wasteland, Zatoichi is attacked by eight enemies, kills them one after another with almost blinding speed, and leaves the gray stones splashed with red blood, in what is, apart from anything else, a rather effective abstract color pattern.

Zatoichi is hardly on screen every moment, or even in every scene. The movie devotes full time to the Ginzo boss (Ittoku Kishibe) and his auditions for a bodyguard, and establishes Aunt O-Ume (Michiyo Ogusu), who befriends the two geishas, O-Kinu (Yuko Daike) and O-Sei (the transvestite Daigoro Tachibana). We get a sense of village life, of gossip and speculation, of keen interest in this curious blind masseur.

And then there is the matter of the music of syncopation. Kitano often combines violence with artistic excursions of the most unexpected sorts, and here he weaves a thread of percussive rhythm through the film. In an early scene, we see four men with hoes, breaking up the earth in a field, and their tools strike the ground in a rhythm that the sound track subtly syncopates with music. Later, there is a duet for music and raindrops. Still later, the men with hoes are stomping in their field, again in rhythm. There is a scene of house-building where the hammers of all the workmen are timed to create a suite for iron against wood. And the final curtain call, worthy of “42nd Street,” begins with a boldly choreographed stomp dance — and then all of the actors come on from the wings and join in the dance, including actors who played some of the characters at younger ages.

This element of the film is almost unreasonably delightful, because completely irrelevant and uncalled-for; Kitano allows fanciful playfulness into what might have been a formula action picture. Remarkably, some of the people I saw the movie with (at two different viewings) came out complaining, as if there were a rigid template for action movies and Kitano had broken the rules. I was surprised and grateful.

Takeshi Kitano, born 1947, has directed 11 films, written 13, and acted in 32 (there are some overlaps). An expert entry in the online encyclopedia Wikipedia says he has also published more than 50 books of poetry, film criticism and fiction, and is also a game show host (one of his shows, retitled “MXC,” plays on Spike TV). He also hosts a weekly talk show of non-Japanese speakers of Japanese, who comment on Japan from their foreign perspectives.

Like many artists of long experience and consistent success, he gives himself permission to work outside the box. “Zatoichi” is not a continuation of the original series (itself available on DVD), but a transformation. It’s the kind of film I more and more find myself seeking out, a film that seems alive in the sense that it appears to have free will; if, in the middle of a revenge tragedy, it feels like adding a suite for hoes and percussion, it does. Kitano is deadpan most of the time on the screen, but I have a feeling he smiles a lot in the editing room.