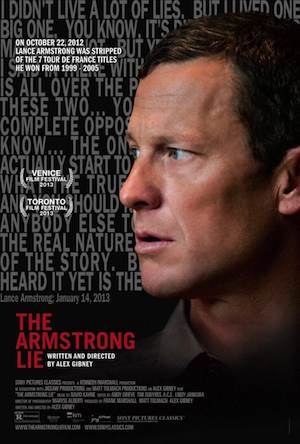

There are two general narratives about Lance Armstrong, and in his new documentary, “The Armstrong Lie,” Oscar-winning director Alex Gibney tackles them both, to varying degrees of success. The first is the fall from grace of an all-American hero following his unprecedented seven-straight-wins at the Tour de France between 1999 and 2005 as well as his unexpected comeback in 2009. The second is, arguably, more interesting, and it’s the fact that practically every single professional cyclist was doping like a clubber at a rave. To paraphrase Deep Throat in “All the President's Men,” everyone was involved.

Of course, this does not detract from the sheer mendacity, belligerence, and simple unpleasantness of Lance Armstrong, who comes across as the sort of guy you definitely would not want to sit down and have a beer with. Gibney originally intended his film to cover Armstrong’s comeback (he’d actually completed the documentary, but hadn’t screened it), but then the doping scandal hit the news. After some time had passed, Gibney changed his focus and revisited the footage. Gibney’s film paints a picture of an overly ambitious man whose supreme, almost clinical, self-confidence severed his connection to reality and truth.

Alex Gibney’s previous films, such as “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” and “Taxi to the Dark Side,” tend to have a much more deliberate and assured structure, which this film lacks. Of course, given the complexity of the case itself, as well as the changing dynamics during production, this is an understandable constant that Gibney had to build his structure around. This makes the film at times have the subtlety of a steamroller (Did you know that the Tour de France is a mad, mad, mad challenge to the body and the mind?). It’s unfortunate, but such is life.

This slightly disjointed aspect of the production makes certain individual scenes and moments stand out, yet they never quite come together. The lack of catharsis allows the viewer enough leeway to judge Armstrong for themselves, and that particular aspect of Gibney’s film is much more fascinating than the “arrogant-pillock-dopes-and-lies” story.

Indeed, Gibney’s film shows that Armstrong was part of a much bigger hypocrisy. The use of the banned red blood cell booster EPO was not just widespread; it was almost universal. EPO remained undetectable for years, and Armstrong, many of his teammates as well as his opponents pumped their blood full of it, and enjoyed the occasional blood transfusion, also banned. The film implies that it would be hard to find anyone who was actually clean in the 1990-2005 period. So no one can actually point the finger too much.

The problem with Armstrong was the way he aggressively chased down and sued (or threatened to sue) people who may have flagged up any alternative to the Armstrong-imposed narrative. There was plenty of evidence, but no one dared stand up to La Armstrong, the ultimate diva of pro cycling.

“The Armstrong Lie” also presents a very close relationship between Lance Armstrong and the International Cycling Union, cycling’s governing board. The ICU and Armstrong had frequent conversations on the cyclist’s latest drug test, with the board representatives amicably warning Armstrong how close he was to getting caught. Gibney doesn’t elaborate on it and purposefully leaves it hanging, but he makes it seem not unfeasible that the whole controversy might have even involved the very head of the UCI.

If anyone dared question him, the film shows, Armstrong retaliated with almost Biblical fury. Armstrong personally went after anyone who even insinuated that something fishy might have been going on. He was a scary, intimidating, and cold man. His story is not a tragedy in the classical sense. It’s a cautionary tale with a very simple and obvious message: don’t be an SOB.

The Armstrong story is fascinating. That someone could get away with such a huge lie in plain sight is terrifying. It’s a bit like the Jimmy Savile mess in the UK in that, to put it simply, people must have known! And some brave people did know and try to talk about it, but if one thing came out of the Armstrong debacle, it’s the knowledge that telling the truth is one thing; finding someone to listen to you is quite another.