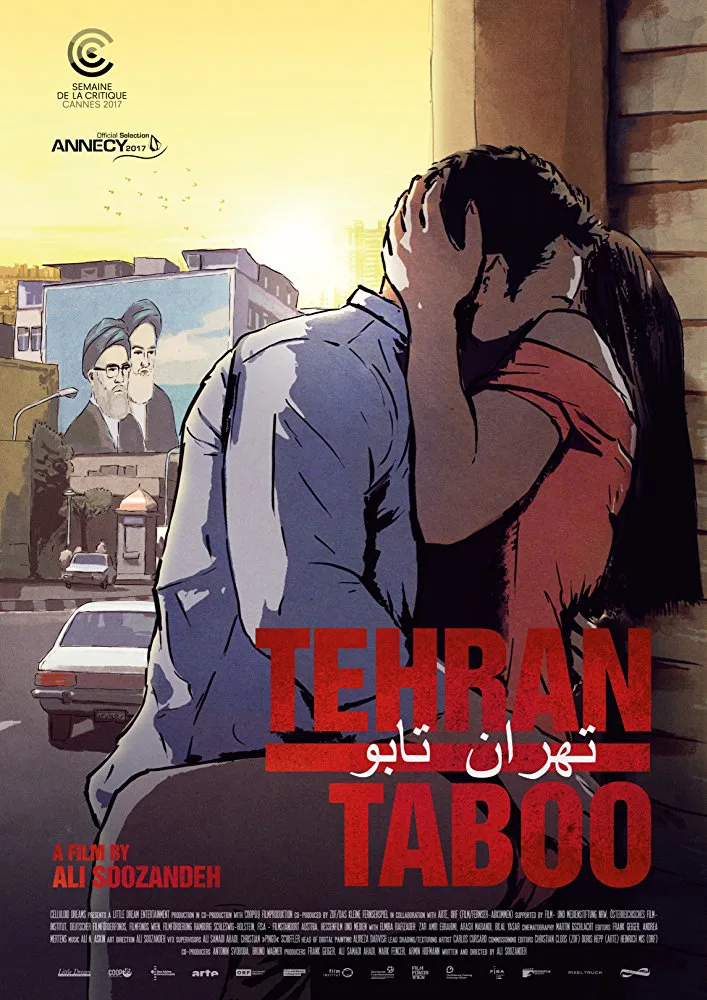

The title of “Tehran Taboo” and some of its advance publicity made it seem like a film designed to shock—a plunge into the seedy underbelly of life in Iran’s capital. But though it does deal with situations that paint this society as troubled and inequitable, especially in regard to issues of sex and gender, the animated film’s tone is neither salacious nor exploitative. Rather, using skillful, involving storytelling and beautifully executed rotoscoped photography, director Ali Soozandeh creates a world of intersecting urban miseries and challenges.

The film will draw understandable comparisons to Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Parranoud’s “Persepolis.” Beyond the fact that both movies are animated, they’re also the kind of films about Iran by Iranian artists that could only be made outside Iran, due to their frankness. (Soozandeh has been based in Germany since 1995 and “Tehran Taboo” is a German-Austrian co-production.) Yet the films are very different in tone, in part because they deal with different eras. While the lyrical “Persepolis” captured some of the heady atmosphere of the Iranian Revolution, “Tehran Taboo” evinces a more caustic tone in exploring the discontents of more recent times.

Soozandeh’s reasons for making the film animated are noteworthy. In interviews he has indicated that he considered shooting it as a regular live-action movie, but realized he would have problems with the backgrounds if he shot in, say, Morocco or Jordan, which sometimes substitute for Tehran in non-Iranian films about Iran. These places just don’t look like Tehran, which has its own textures and distinct cultural atmosphere. So the filmmaker went the rotoscoping route, which involves shooting live actors in a studio, then feeding their images into a computer and using CGI to supply the settings and backgrounds around them.

The success of this method in “Tehran Taboo” is twofold. First, as intended, it gives us innumerable views of Tehran that appear very authentic. (Having visited the city a number of times, I was struck by how familiar and exact many of the details are.) But beyond that, the rough beauty of the animated images, besides having a fascination of their own, keep the viewer at a certain remove from events that might be more off-putting if seen in live-action.

A scene at the film’s opening illustrates this quality as well as offering a sharp example of the film’s focus on sexual hypocrisy. In a car, a prostitute named Pari (Elmira Rafizadeh) gives a blowjob to a client as he drives down a busy Tehran street. Though her mute young son can’t see them, he’s in the back seat—a detail that might be harder to pull off in live-action. As for the hypocrisy: the scene comes to a screeching halt, literally, when the man sees his daughter walking down the street with a guy and crashes the car in rage.

We then follow Pari, who is dealing with the burden of having an imprisoned drug addict husband she wants to divorce. When she goes to the Islamic Revolutionary Court, the rotund judge there (Hasan Ali Mete) offers her a deal. In exchange for her sexual favors, he sets up her in her own apartment, with her son. The arrangement has its advantages, and leads her into friendship with a neighbor named Sara (Zara Amir Ebrahimi), who’s got her own set of problems: expecting a baby after two miscarriages, she feels cooped up living with her in-laws yet her banker husband (Mohsen Bayram) doesn’t want her working outside the home.

The film’s other main storyline kicks off when Babak (Arash Marandi), a talented but impecunious young musician, meets a girl in an underground rave and has sex with her in the toilet. The next day she gets in touch to say that she was a virgin and that if he doesn’t have her maidenhead artificially restored, the brute she’s supposed to marry will kill them both. Thus do Babak and his new friend set off on an odyssey through Tehran’s sleazy medical underworld looking for an operation that may or may not exist.

Although the primary female characters here—and to a lesser extent, some of the men—are trapped in the strictures of a traditional patriarchal society that’s enforced by a theocratic government, the film wisely doesn’t come across as a two-dimensional polemic. That’s largely because Soozandeh’s storytelling is so engaging and nuanced. The characters are drawn (and acted) so compellingly that we are pulled into the complexities of their stories and personalities. The world here is one where everyone is out for him- or herself, but necessarily makes bargains at every turn to get by. It’s not a place of simplistic, easily dismissed stereotypes. Even the mullah is a genial, self-aware sort.

Although “Tehran Taboo” is not a film that could have been made in Iran, Iran-based filmmakers including Jafar Panahi, Abbas Kiarostami and others have covered most or all of the sensitive and controversial topics it addresses in their own ways. It thus is not quite as original as it may appear to some non-Iranians.

Additionally, Iranian friends I’ve talked to about the film have said that it’s somewhat outdated: many of the situations and attitudes it depicts—the concern with virginity, “morality police” pursuing couples who aren’t married, etc.—are things that were prominent 15 or 20 years ago, nearer the time when Soozandeh lived in Iran, but are much different today. That was my impression, too, when I visited Tehran last spring for the first time in over a decade: it’s a place where public and private mores seem to be changing as rapidly as the skyline.