The phrase “Never Forget” has long been associated with the Holocaust. It’s a pushback against the type of willed, collective amnesia that allows not just the perpetrators of atrocities but their descendants to go through life unburdened by guilt for war crimes and the privileges accrued as a result of their commission. The documentary “Tantura” shows how selectively the phrase is applied when the subject is the founding of Israel, which killed and displaced Palestinians and had a negative multigenerational ripple effect that continues into the present day. The movie focuses on the fate of Palestinian residents of the title village in the summer of 1948. A mass murder by Israeli soldiers was part of a grim event that included beatings, rapes, and looting.

“Tantura” is an ensemble work with a lot of voices. But the main narrative thread is research by a Haifa University graduate student named Teddy Katz about the effect of the 1948 war on five villages, including Tantura. Katz conducted 140 hours of audio interviews with 135 people, both Palestinians and Israeli witnesses to (and participants in) the events at Tantura. Then he published a thesis in 1998 concluding that there was a massacre of 200-250 Tantura Palestinians, mostly men, by IDF’s Alexandroni Brigade, and that the victims were buried in mass graves. He received the highest grade possible on a thesis and graduated with honors.

When the Times of Israel published an article about Tantura that relied heavily on Katz’s work, it sparked such ire that Katz became the subject of a libel suit by a group of his subjects (even though they spoke to him voluntarily, and everything was on tape). In order to settle the case out of court and spare the University public outrage, Katz was was compelled to sign a retraction saying the massacre did not happen, and the judge closed the case. Days after that, Katz tried to withdraw his retraction, saying that he had signed it “in a moment of weakness and that he already deeply regretted it,” but the judge kept the case closed, and the university revoked his degree.

The judge who (barely) presided over the libel case listens to some of the tapes on camera for the first time and indicates that if she’d heard them 22 years ago, she would have been inclined to side with Katz. But one still wonders if another result would have been possible, given how human beings are, how tightly nations cling to self-flattering foundational myths, and how the brain tends to process (and then reject) guilt, responsibility, and reckoning. Finally, near the end of the film, three women and one man who were residents of the original kibbutz created in Tantura after the massacre and displacement argue about whether a memorial to the victims should be allowed on site.

One of the on-camera interviewees describes the incidents at Tantura as having been not merely buried but destroyed. Willed forgetting is the movie’s focus, and the film predictably has limited success in attempting to compel remembrance in most of its participants, who tend to retreat into variants of, “Well, it was war, and bad stuff happens in war,” or “It was a long time ago,” or “We were trying to found a nation so we wouldn’t have to go through another Holocaust,” or “The Arabs were ruthless, so we did what we had to do.”

Every existing nation is founded to some extent on the agonies of murdered and displaced prior residents, the United States included, and the descendants of the winning side always say things like that. So it’s not a surprise that they get repeated here, much less to learn that there were subsequent attacks on Katz’s thesis, including a reevaluation by the rector of Haifa University that called his research methods and his advisors’ oversight of them flawed, and concluded that there was no way to prove that over 200 people were killed, the number might’ve been as low as 40 or 50, and it was impossible to establish that every single one of them was a murder victim.

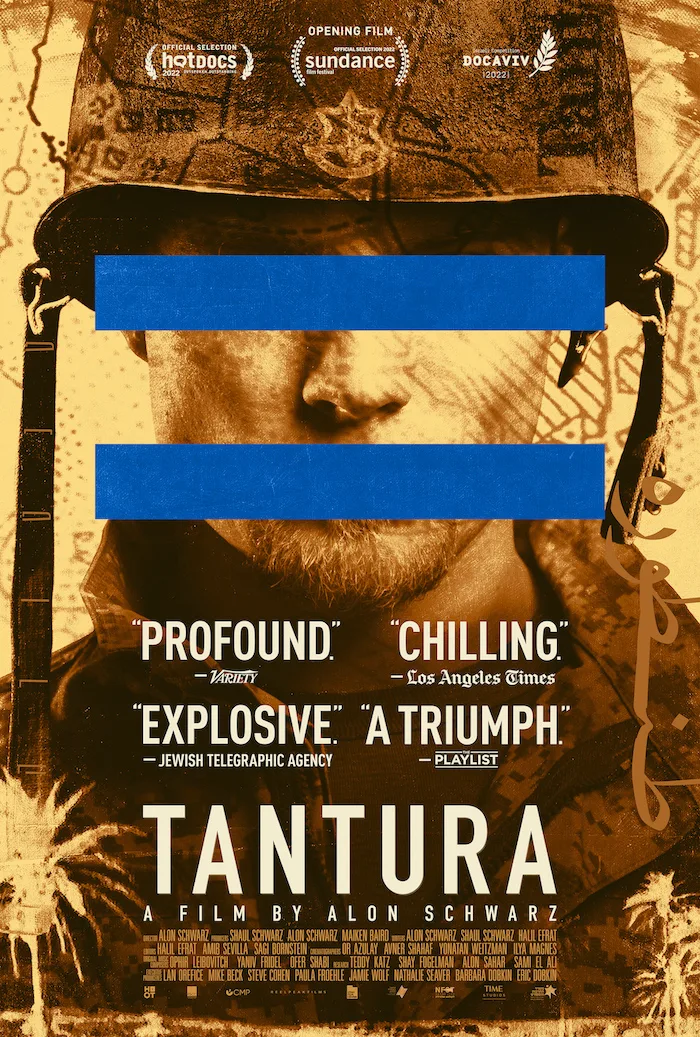

Filmmaker Alon Schwarz was aware of the political minefield he was walking into by choosing this subject, and that’s undoubtedly why the storytelling treads lightly. The result is a bit fragmented and unfocused in its arrangement of different voices, at times letting things “drop,” as one soldier on the audiotape repeatedly puts it, when pushing and probing might have yielded more insight. (Maybe Schwarz didn’t feel he could push things further because so many of his camera subjects were in their eighties and nineties and were already uncomfortable being challenged.) And while one understands why only Israelis were interviewed—Schwarz seems to be going for something like the Claude Lanzmann and Marcel Ophuls Holocaust documentaries that confronted perpetrators and enablers of war crimes—there are points when the viewer might still wonder if the result would have been richer, though messier and more explosive, if he’d widened the pool of subjects (remember, the demographic makeup of Katz’s original batch of tapes was 50/50).

But the end product was bound to be controversial anyway, in the manner of pretty much every piece of filmed or written media focusing on Jewish-Arab history in the Middle East. Just bringing up the subject tends to start fights. Israelis call the events of 1948 The War for Independence, while Palestinians call it Nakba, or The Catastrophe. It’s hard to imagine how the two could be reconciled, and “Tantura” doesn’t try. It has its hands full trying to establish what happened and encouraging participants and beneficiaries to accept what it meant.

Now playing in theaters.