The recent death of Leni Riefenstahl was a reminder of the “de-Nazification” process in which Allied tribunals investigated possible Nazi collaborators. The subjects were not blatant war criminals like those tried at Nuremberg, yet neither were they innocent bystanders. They were German civilians of power or influence, whose contribution to the war now had to be evaluated.

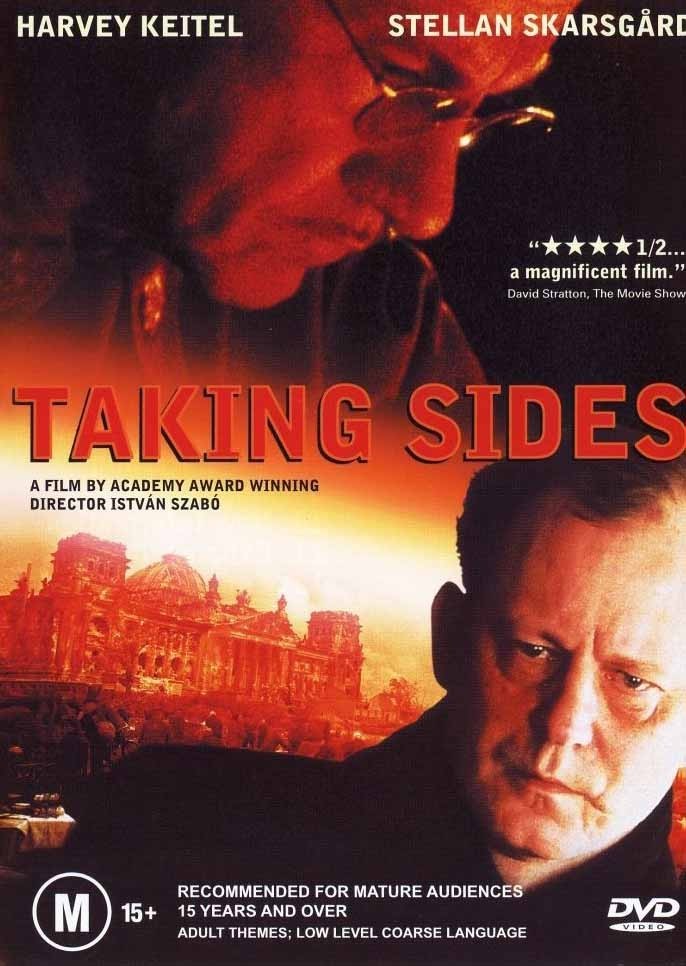

Some said they didn’t agree with the Nazis and never joined the party, but merely continued in their civilian jobs and tried to remain outside politics. Such a man was Wilhelm Furtwangler, the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic, who was known as “Hitler’s favorite conductor,” just as Riefenstahl was his favorite filmmaker. “Taking Sides” is the record of Furtwangler’s postwar interrogation at the hands of Steve Arnold, a U.S. Army major who in civilian life had been an insurance investigator, and approaches the great man as if Furtwangler’s restaurant had just burned down and he smelled of kerosene.

Many German artists, Jewish and not, fled their country with the rise of Hitler. Furtwangler’s contemporary and rival Otto Klemperer left in 1933 and took over the podium at the Los Angeles Philharmonic. But Furtwangler (Stellan Skarsgard) remained behind, and tells Arnold (Harvey Kietel) he did it out of loyalty to his music, his orchestra and his nation. Art for him was above politics, he said, and he never joined the Nazi party or gave the Nazi salute. Ah, says Arnold, but you played at Hitler’s birthday party. Furtwangler splits hairs: He played at an event the night before.

To remain in Germany and not be a loyal Nazi was “to walk a tightrope between exile and the gallows,” he says. The impression he wants to give is that he never liked Hitler, never liked the Nazis, was loyal to the decent traditions of Germany’s past. Yes, but if the Nazis had won — would he have then tried to slip out to some safe haven? That is the great question with Riefenstahl, too; we can’t help suspecting their postwar dislike for the Nazis was greatly amplified by their defeat.

“Taking Sides,” based on a play by Ronald Harwood (“The Dresser“), has been directed by the distinguished Hungarian Istvan Szabo, whose great “Mephisto” (1981) tells the story of an actor whose career is promoted by the Nazis he loathes; he plays the roles of his dreams but loses his soul. Szabo himself remained in Hungary during the Soviet occupation, true to his country, loyal to his art, working with the Soviets but hating them, so this material must resonate with him. “Mephisto” was at one level clearly about Soviets, not Nazis, and was about Szabo’s own situation. In “Mephisto,” as the title signals, the hero sold his soul to evil.

But Furtwangler is a more complicated case, and one of the problems of the film is that it doesn’t clearly take sides. Another is that Furtwangler is presented as a man of pride and character, and the American comes across as a vulgar little toady who wants to impress his superiors by bagging the great man: “I’m not after small fish,” he brags. “I’m after Moby Dick.” He calls the conductor a “band leader,” and says “musicians, morticians, they’re all the same.” Major Arnold treats Furtwangler with deliberate contempt, making him wait for hours when he arrives on time for appointments and playing childish games involving the chair he sits in. Sharing his office are an aide and a secretary: Lt. David Wills (Mortiz Bleibtreu), a German Jew in the American Army, and Emmi Straub (Birgit Minichmayr), whose father was one of the Nazi officers killed in a belated uprising against Hitler. Both grew up thinking of Furtwangler as a great man, both are shocked by the contempt with which Arnold treats him, and Emmi finally announces she is leaving: “I’ve been questioned by the Gestapo — just like that.”

Furtwangler’s case is a murky one. Yes, he made anti-Semitic comments. But he also helped many Jewish musicians escape to Switzerland and the West. Yes, his recording of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony was played on German radio after Hitler’s death. But of course it was. Yes, he was naive to think that art and politics could be kept separate. But you know how those longhairs are. The de-Nazification courts eventually cleared him, but he remained under a cloud and never toured in America.

The movie is both interesting and unsatisfying. The Keitel performance is over the top, inviting us to side with Furtwangler simply because his interrogator is so vile. There are maddening lapses, as when Furtwangler’s rescue of Jewish musicians is mentioned but never really made clear. But Skarsgard’s performance is poignant; it has a kind of exhausted passivity, suggesting a man who once stood astride the world and now counts himself lucky to be insulted by the likes of Major Arnold. Furtwangler chose the wrong side, and tried to have it both ways, living at arm’s length with the Nazis. Klemperer left not necessarily because he was Furtwangler’s moral superior, but because as a Jew, it was a matter of survival. Furtwangler, ambitious, vain like many conductors, perhaps under the illusion that Hitler would win, stayed and held his nose.

At the end of a movie that never clearly chooses sides, Szabo finds the perfect image to close with. It’s from an old newsreel of the real Furtwangler, conducting the Philharmonic for an audience of Nazi officers. After the concert is over, an officer approaches the podium and shakes his hand. And then Furtwangler quietly takes a handkerchief out of his pocket and wipes off his hand. Szabo shows the gesture a second time, in closeup. And there you have it. Better not to shake hands with the devil in the first place.