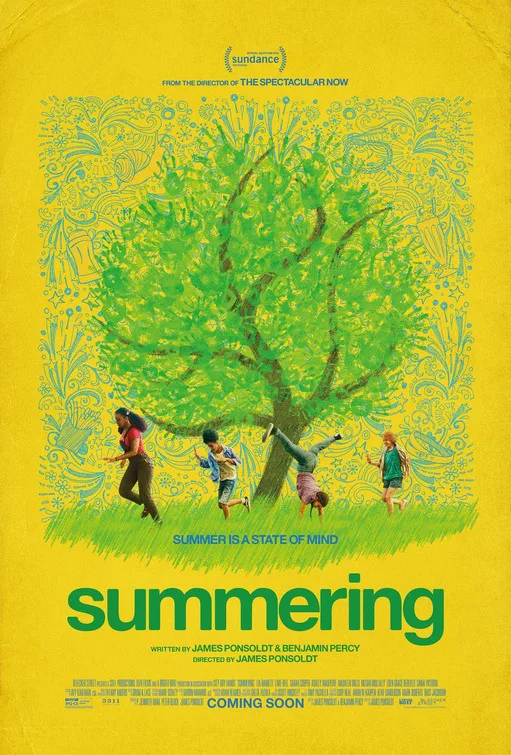

The opening sequence of James Ponsoldt’s “Summering” sets up an idyllic summer in the suburbs, as four friends run carefree from yard to yard through sprinklers casting rainbows over the perfectly cut grass. Everything has a nostalgic patina to it, down to the treacly score mixed with the innocent laughter of the girls at play. “The summer when it lasts, everything is alive and anything’s possible … at least it feels that way,” a girl named Daisy (Lia Barnett) shares over a narration that is sporadically deployed throughout the film.

This feeling is surely the aim of Ponsoldt and co-writer Benjamin Percy’s script. Unfortunately, the film never once embraces the immediacy of that feeling. Instead it’s drenched in the kind of nostalgia that adults have whenever the urge hits to think back on their childhood, not that scary uncertainty of a pre-teen headed slowly towards their teen years and all that lay beyond.

The girls—Daisy, Dina (Madalen Mills), Mari (Eden Grace Redfield), and Lola (Sanai Victoria)—grasp at the dog days of summer, dreading the separation that will come not just as their break ends, but as they head to different middle schools and leave childhood, and possibly their friendship behind. They decide to leave something at the tree they’ve turned into an altar called Terabithia, a nod to Katherine Paterson’s beloved children’s novel Bridge to Terabithia. Once there Daisy finds something in the bushes that turns out to be a dead man in a thrift store suit. The girls argue about whether to report what they’ve found to the authorities and their ultimate decision becomes the first of many head-scratcher choices the filmmakers make.

Comparisons to Rob Reiner’s “Stand By Me,” itself an adaptation of a novella by Stephen King, are hard to resist on a plot point level. However, that film made its nostalgia explicit through its frame narrative. It also firmly understood how children talk to each other: A mixture of inside jokes, crudeness, and of course heartfelt sharing of fears about the future and painful, often secret, truths about the present. These girls do some of that, but mostly they talk about their helicopter parents. The way they talk about their upbringing sounds more like when an adult recalls how their parents never let them have sugary cereal, not how children talk about their parents in the present. The dialogue in “Summering” is far too wistful.

In one strange sequence the girls go to a bar where they think they can discover the name of the dead body. The bartender vaguely remembers him and says he played video games—but not a “Switch” like the girls suggest. An old-fashioned arcade game. The girls discuss how maybe one of their moms may have played that kind of video game and the whole thing is coated in a nostalgia for a different era. It’s as if Ponsoldt and Percy wanted to write about their own childhood, but couldn’t sell a period piece. They never once demonstrate a real understanding or curiosity for it is like being a child now, amidst all our technology and turmoil.

From here, the film oscillates from clichéd coming-of-age style dialogue and situation to psychological horror as the girls begin to hallucinate the man’s face everywhere they look. Ponsoldt is not able to mesh these tones well at all, with each jump scare telegraphed a mile away and landing with a thud. Eventually, the girls begin to doubt they ever did really find a body; their certainty fades like the summer heat. This could have worked as a metaphor for the way so many memories from childhood become fuzzy, straddling the line between reality and our own mythology.

Yet because there are so many scenes that make it clear they did indeed find this body, the metaphor collapses in on itself. One such scene is one of the most completely miscalculated scenes in a film all year. After Dina finds its location on the dark web (yes, these pre-teens can apparently surf the dark web), Daisy shoots open the storage shed where the man must have been living. No one questions why Daisy has a handgun in her backpack. The storage shed has all its lights on and a black-and-white television plays in the background. Where is the electricity coming from? Why would a houseless man leave all of these lights on? Absolutely nothing about this scene works.

Worst of all, “Summering” thinks we should be invested in these girls and their coming-of-age issues while they’ve left the body of a houseless individual to rot in the dirt because they don’t want their mothers putting them in therapy? Because they want to go on an investigation together during the last three days of summer? The trip to see the dead body in “Stand By Me” has heft to it because they’ve heard it’s a kid like them. They’ve all already endured hardships. They seek their own mortality in the body.

What do these girls see? Do they even see the humanity in this death? Children can be selfish, sure, but this selfish? It’s hard to buy. At one point, we learn that Daisy’s father has gone missing and no one is looking for him. Eventually we discover the truth, but only vaguely. It’s handled in such a way that probably felt deep on the page, but in execution is undercooked (and overacted by Lake Bell and Dale McKeel as Daisy’s parents).

As the film ends, with very little resolution and no consequences for their actions, the song “Seven” from Taylor Swift’s Folklore plays. In the song, Swift sings from the point of view of a 30-year-old looking back at her inability to help her childhood best friend from parental abuse. It’s a fitting needle drop in that it masks horrific details with beautiful music, just as the filmmakers mask horrific actions with beautiful cinematography. While Swift knows the story she’s telling is horrifying, filtered through memory and years of guilt, there’s no indication that the filmmakers of “Summering” understand just how reprehensible their narrative is. The nostalgia of Ponsoldt’s film is curdled and rotten underneath its summery sheen.

Now playing in theaters.