Sometimes you run across a movie that’s far from perfect and yet it contains things that are so good they take your breath away. “Street Smart” is a movie like that – a clever thriller with a lot of unbelievable scenes and a sappy ending, but two wonderful performances.

The performances are by Morgan Freeman, as a Times Square pimp, and by Kathy Baker, as one of the hookers he controls. They play their characters as well as I can imagine them being played. Freeman has the flashier role, as a smart, very tough man who can be charming or intimidating – whatever’s needed. Baker is a small-town girl who has been a hooker for years, who lives by the rules of the street but still has feelings.

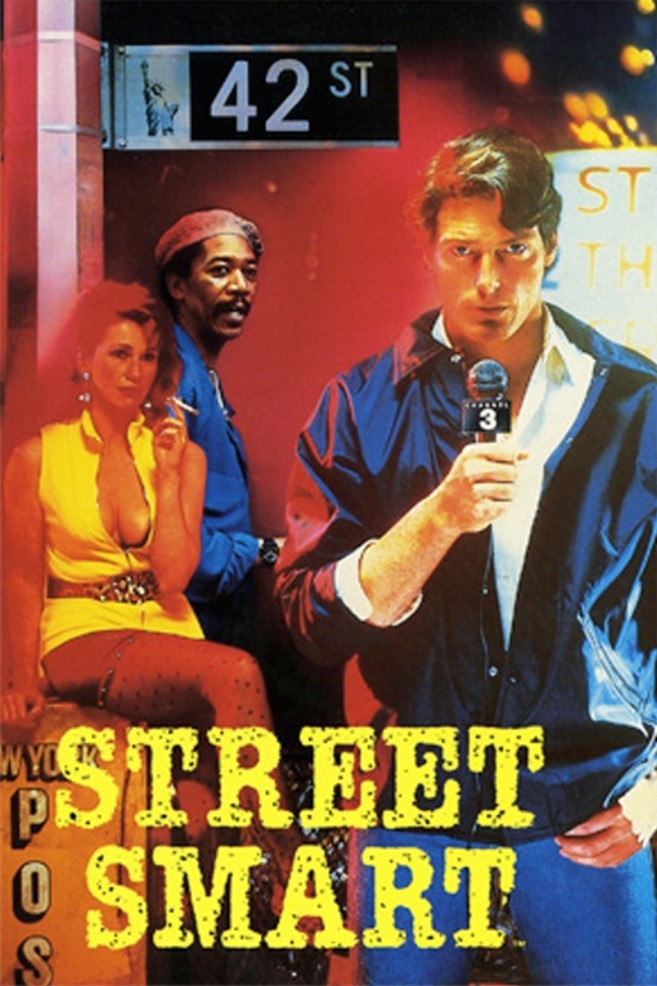

Surrounding their performances is a plot that would have been interesting if it had been handled more realistically. Christopher Reeve plays a magazine reporter who concocts a completely fictional story about a colorful pimp. After the story is published and creates a sensation, the district attorney becomes convinced that the subject of the story is really the Freeman character – who is on trial for murder.

He subpoenas Reeve’s notes, but of course there aren’t any.

From this promising beginning, “Street Smart” takes its story in two different directions. On one hand, we get a satirical view of the New York publishing and television industries, with Andre Gregory as the cynical magazine publisher and Reeve as an overnight journalism star who is instantly hired as a TV street reporter. On the other hand, we get Reeve trying to cover his tracks by going back and doing the reporting he should have done in the first place.

This second story – which involves Freeman and Baker – is much more interesting than the first. The pimp quickly figures out Reeve’s problem and offers him a deal: He’ll agree that he was the subject of the fictional story if Reeve provides him with an alibi. Reeve refuses.

Freeman turns dangerous and violent: He’s facing a life sentence and, for him, this isn’t a matter of ethics but of his life.

The second hour of “Street Smart” almost seems to be scenes from two different movies. Freeman’s dialogue is particularly good, as he analyzes Reeve’s motives, talks about people who condescend to him and terrorizes Baker for becoming Reeve’s friend. There is one powerful, frightening scene where he threatens her with scissors; the power on the screen reminded me of vintage De Niro or Pacino.

Many of the street scenes have the uncanny feeling of real life, closely observed. For example, look at the scene where Freeman and his sidekick take Reeve for a tour of the streets in their Cadillac. When Freeman decides to discipline one of his girls, he squeezes her into the front seat, too, so Reeve is forced to confront reality up close, and maybe get blood on his suit. The staging of this scene – four people all in the front seat – is what makes it work.

The movie’s other story, the one involving the magazine and TV news, is sort of silly. It’s impossible to believe Reeve would so quickly become a TV newsman, difficult to believe most of the stories he reports, and incredible that Baker somehow always knows exactly where, in all of Manhattan, Reeve is going to be doing his next remote TV report.

The end of the movie is also a disappointment. It’s yet another shootout. Screenwriters have grown so lazy in recent years that it’s almost too much to ask them to resolve a plot on human terms. The last reel of most thrillers now involves the obligatory death of the villain, as if death were a solution. Since we know that’s how the movie will end, the last reel is a loss – a waste of the movie’s own time. And in “Street Smart,” where Freeman creates such an unforgettable villain, I really resented it when he wasn’t given the chance to participate in his own fate.

As a film school exercise, would-be screenwriters should be required to rewrite thrillers like this, with real human endings instead of the copout of the standard sequence: chase, shootout, death, fade out. When an actor like Freeman goes to the trouble of creating a great character, the film should go to the trouble of providing him with a final scene.