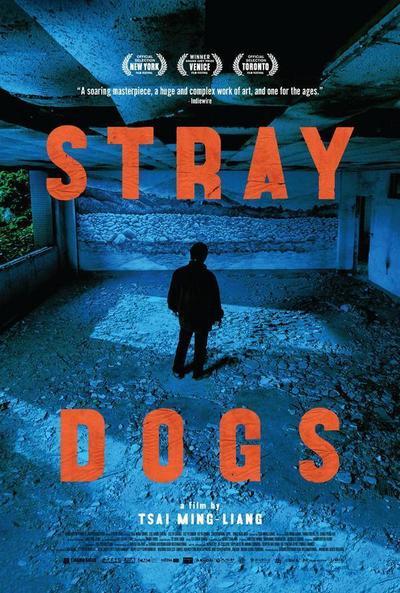

“Stray Dogs,” Tsai Ming-Liang’s first feature in five years, is a mysterious and deliberately prolonged series of tableaus about the fragility of flesh and the smallness of humanity, among other things.

Like most of his films—but particularly ones built around very long takes, such as 2003’s masterful “Goodbye, Dragon Inn”; his 35-minute short “Madame Butterfly,” which has just three shots; and this one—it refuses to engage with anything resembling conventional, commercially viable storytelling. This is a director whose 1997 film “The River” kicked off with a locked-down shot of an escalator on which the main action was a wordless exchange of glances between a man and a woman who didn’t enter the frame for half a minute. Compared to Tsai, the hypnotically austere Apichatpong Weerasethakul (“Syndromes and a Century,” “Tropical Malady”) seems fidgety.

Before he decided to focus on cinema, Tsai worked in experimental theater, and if you’ve decided to sample his work for the first time starting with this new feature, you should bear that in mind as you watch. There is no plot to speak of here, nor are there any characters—not in any conventional sense of the terms. We’re not watching people pursue specific goals, solve specific problems, and learn and grow on the way to catharsis. We’re just watching people exist and intuiting the story that drives them from situation to situation, and then moving on to connect the people and the landscape with basic, deep concerns: the isolation and disconnection of life in anonymous big cities; the sense of being suspended in a perpetual present even as time rolls on; the tactility of forests and roads, rooms and furniture, clothes and books, bedsheets and skin. Cinema often lures us into thinking about what people and places and situations represent rather than appreciating their essence. Tsai’s films push against that tendency. They might owe more to documentaries, or to theatrical installations, than to most traditional scripted features. The last ten minutes of this movie consist of an unbroken long take of characters staring at a mural.

The movie begins with a long shot of a mother sitting on the edge of a bed, brushing her hair as she watches her two children (Lee Yi Cheng and his sister Li Yi Chieh) sleep. This woman, presumably the children’s mother, vanishes from the story, and the siblings are next seen living with their dad (Lee Kang-Sheng) inside a shipping container and making pocket money holding up advertising signage at a busy urban intersection. The film continues like that, observing the harshness of the children’s lives, and their father’s exhaustion and seemingly constant depression (he seems to spend a lot of the money they make as a family on alcohol and smokes). “Heaven and Earth are heartless, treating creatures like straw dogs,” says the Tao Te Ching.

In one of the movie’s longest, most wrenching scenes—one that oddly mirrors the opening shot—the father joins his two kids in bed, then rolls over, and as the camera follows his movement, it reveals a sort of mother-substitute figure: a head of cabbage with a mouth and eyes drawn on it, nestled awkwardly into a sweater. The man becomes unnerved by it, then vigorously mimes smothering it, then finally devours it, weeping cathartically.

This is one of the strangest and most upsetting sequences I’ve seen in a film in a long time, precisely because the father never verbalizes the fluctuations in his emotions. There’s no monologue, no voice-over. We’re just watching a man lose it, step by step, until he finally seems to implode in despair, then slowly ramp down and locate his center again. Something about it reminded me of the scenes in “Twin Peaks” where Leland Palmer (Ray Wise) weeps as he dances with an imagined version of his murdered daughter to the tune of “Pennsylvania 6-5000.” I’ve watched that scene many times in the presence of other people; they always laugh at first, albeit nervously, but they always stop laughing as it goes on and on, and it becomes clear that we’re in the presence of a man whose tether to reality has snapped.

Scene after scene in “Stray Dogs” drives home the difficulty of daily existence while also (perhaps paradoxically—or not, if you’re Buddhist, as Tsai is) making you appreciate the incidental, beautiful sights and sounds that our busyness or our pain might otherwise cause us to ignore: the way tall swamp grass rustles as the father pushes a small wooden rowboat through it; the hiss of rain on wet ground and foliage in the storm sequence; the play of sunlight on the tile and white glass of a luxury apartment that the father has wandered into (briefly experiencing, and imagining, a life of comfort). This is, as you’ve surely gathered, the sort of film that does not have what studio executives would call “a pre-sold audience.” It asks a lot of us. In fact it asks us to set aside everything we’ve been conditioned to think movies are, and roll with a different way of seeing and hearing things, and connect.