The animals do not speak in “Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron,” and I think that’s important to the film’s success. It elevates the story from a children’s fantasy to one wider audiences can enjoy, because although the stallion’s adventures are admittedly pumped-up melodrama, the hero is nevertheless a horse and not a human with four legs. There is a whole level of cuteness that the movie avoids, and a kind of narrative strength it gains in the process.

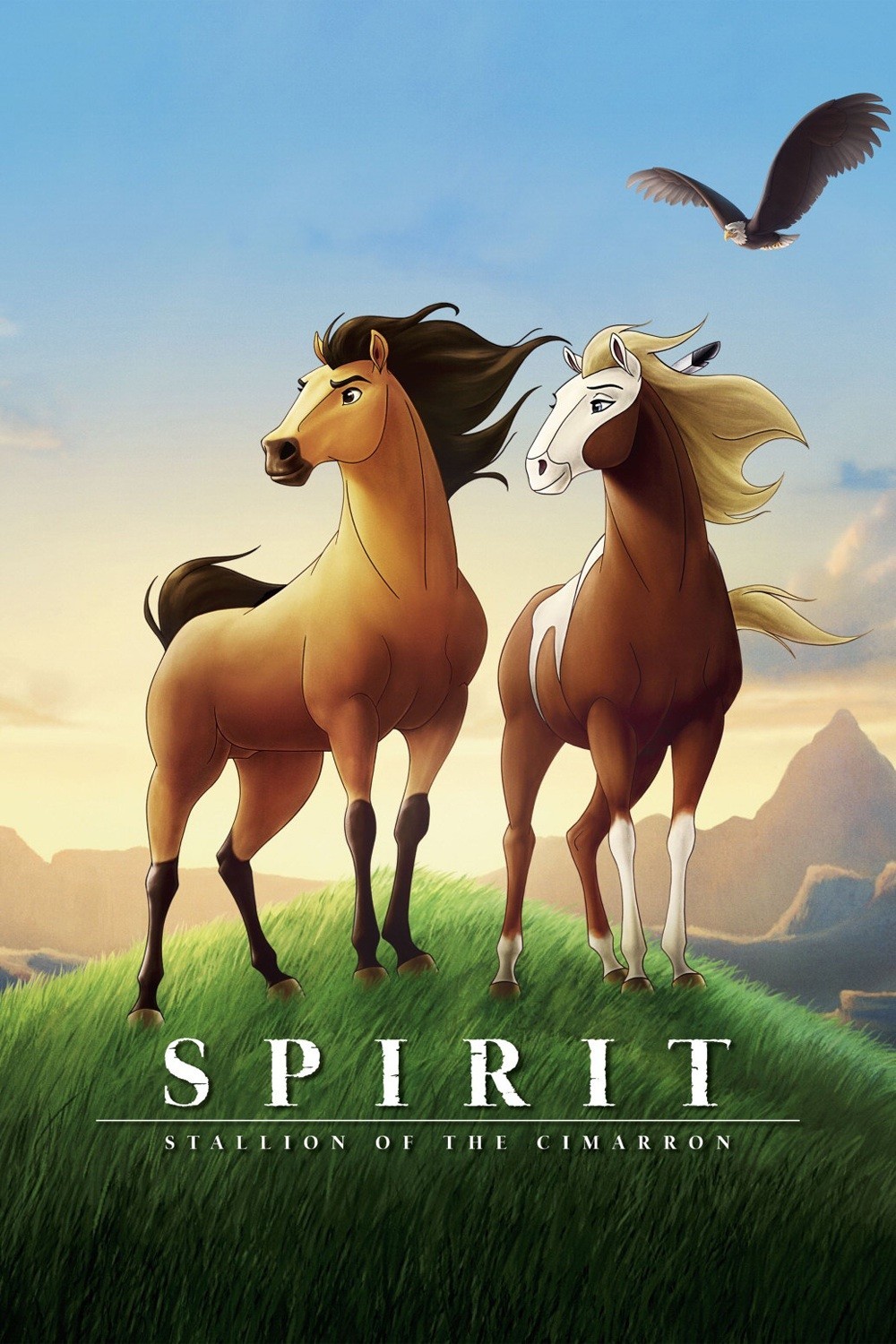

The latest animated release from DreamWorks tells the story of Spirit, a wild mustang stallion, who runs free on the great Western plains before he ventures into the domain of man and is captured by U.S. Cavalry troops. They think they can tame him. They are wrong, although the gruff-voiced colonel (voice of James Cromwell) makes the stallion into a personal obsession.

Spirit does not want to be broken, shod or inducted into the Army, and his salvation comes through Little Creek (voice of Daniel Studi), an Indian brave who helps him escape and rides him to freedom. The pursuit by the cavalry is one of several sequences in the film where animation frees chase scenes to run wild, as Spirit and his would-be captors careen down canyons and through towering rock walls, dock under obstacles and end up in a river.

Watching the film, I was reminded of Jack London’s classic novel White Fang, so unfairly categorized as a children’s story even though the book (and the excellent 1991 film) used the dog as a character in a parable for adults. White Fang and Spirit represent hold-outs against the taming of the frontier; invaders want to possess them, but they do not see themselves as property.

All of which philosophy will no doubt come as news to the cheering kids I saw the movie with, who enjoyed it, I’m sure, on its most basic level, as a big, bold, colorful adventure about a wide-eyed horse with a stubborn streak. That Spirit does not talk (except for some minimal thoughts that we overhear on voice-over) doesn’t mean he doesn’t communicate, and the animators pay great attention to body language and facial expressions in scenes where Spirit is frightened of a blacksmith, in love with a mare, and the partner of the Indian brave (whom he accepts after a lengthy battle of the wills).

There is also a scene of perfect wordless communication between Spirit and a small Indian child who fearlessly approaches the stallion at a time when he feels little but alarm about humans. The two creatures, one giant, one tiny, tentatively reach out to each other, and the child’s absolute trust is somehow communicated to the horse. I remembered the great scene in “The Black Stallion” (1979) where the boy and the horse edge together from the far sides of the wide screen.

In the absence of much dialogue, the songs by rocker Bryan Adams fill in some of the narrative gaps, and although some of them simply comment on the action (a practice I find annoying), they are in the spirit of the story. The film is short at 82 minutes, but surprisingly moving, and has a couple of really thrilling sequences, one involving a train wreck and the other a daring leap across a chasm. Uncluttered by comic supporting characters and cute sidekicks, “Spirit” is more pure and direct than most of the stories we see in animation–a fable I suspect younger viewers will strongly identify with.