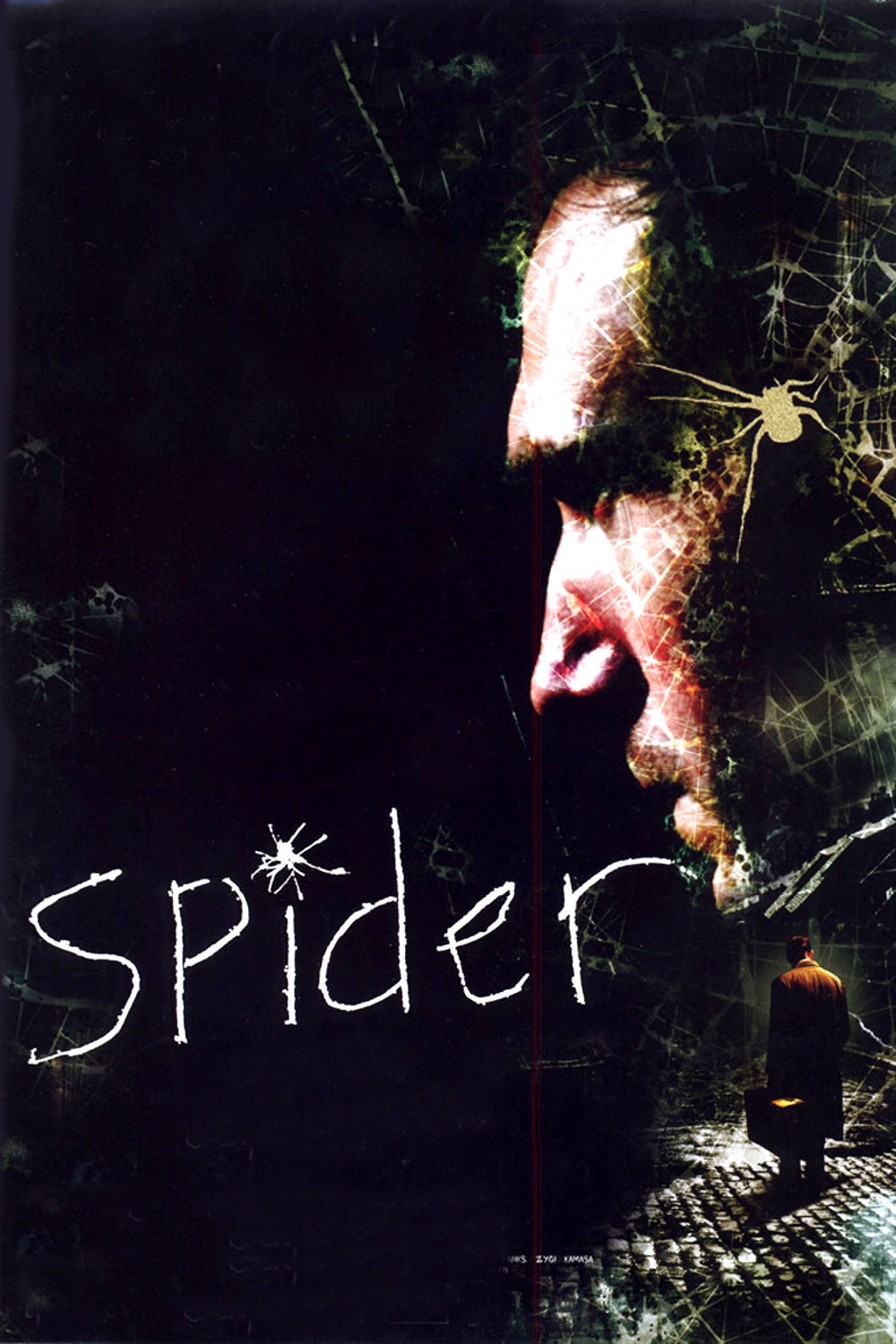

He looked like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them … So Ahab is described in Moby Dick . The description matches Dennis Cleg, the subject (I hesitate to say “hero”) of David Cronenberg’s “Spider.” Played by Ralph Fiennes, he is a man eaten away by a lifetime of inner torment; there is not one ounce on his frame that is not needed to support his suffering. Fiennes, so jolly as J. Lo’s boyfriend in “Maid in Manhattan,” looks here like a refugee from the slums of hell.

We see him as the last man off a train to London, muttering to himself, picking up stray bits from the sidewalk, staring out through blank, uncomprehending eyes. He finds a boarding house in a cheerless district and is shown to a barren room by the gruff landlady (Lynn Redgrave). In the lounge, he meets an old man who explains kindly that the house has a “curious character, but one grows used to it after a few years.” This is a halfway house, we learn, and Spider has just been released from a mental institution. In the morning, the landlady bursts into his room without knocking–just like a mother, we think, and, indeed, later he will confuse her with his stepmother. For that matter, his mother, his stepmother and an alternate version of the landlady are all played by the same actress (Miranda Richardson); we are meant to understand that her looming presence fills every part of his mind that is reserved for women.

The movie is based on an early novel by Patrick McGrath. It enters into the subjective mind of “Spider” Cleg so completely that it’s impossible to be sure what is real and what is not. We see everything through Spider’s eyes, and he is not a reliable witness. He hardly seems aware of the present, so traumatized is he by the past. Whether they are trustworthy or not, his childhood memories are the landscape in which he wanders.

In flashbacks, we meet his father, Bill Cleg (Gabriel Byrne), and mother (Richardson). Then we see his father making a rendezvous in a garden shed with Yvonne (also Richardson), a tramp from the pub. The mother discovers them there, is murdered with a spade and buried right then and there in the garden, with the little boy witnessing everything. Yvonne moves in, and at one point tells young Dennis, “Yes, it’s true he murdered your mother. Try and think of me as your mother now.” Why are the two characters played by the same actress? Is this an artistic decision, or a clue to Spider’s mental state? We cannot tell for sure, because there is almost nothing in his life that Spider knows for sure. He is adrift in fear. Fiennes plays the character as a man who wants to take back every step, reconsider every word, question every decision.

There is a younger version of the character, Spider as a boy, played by Bradley Hall. He is solemn and wide-eyed, is beaten with a belt at one point, has a childhood that functions as an open wound. We understand that this boy is the most important inhabitant of the older Spider’s gaunt and wasted body.

The movie is well made and acted, but it lacks dimension because it essentially has only one character, and he lacks dimension. We watch him and perhaps care for him, but we cannot identify with him because he is no longer capable of change and decision. He has long since stopped trying to tell apart his layers of memory, nightmare, experience and fantasy.

He is lost and adrift. He wanders through memories, lost and sad, and we wander after him, knowing, somehow, that Spider is not going to get better–and that if he does, that would simply mean the loss of his paranoid fantasies, which would leave him with nothing. Sometimes people hold onto illnesses because they are defined by them, given distinction, made real. There seems to be no sense in which Spider could engage the world on terms that would make him any happier.

There are three considerable artists at work here: Cronenberg, Fiennes and Richardson. They are at the service of a novelist who often writes of grotesque and melancholy characters; he is Britain’s modern master of the gothic. His Spider Cleg lives in a closed system, like one of those sealed glass globes where little plants and tiny marine organisms trade their energy back and forth indefinitely. In Spider’s globe, he feeds on his pain and it feeds in him. We feel that this exchange will go on and on, whether we watch or not. The details of the film and of the performances are meticulously realized; there is a reward in seeing artists working so well. But the story has no entry or exit, and is cold, sad and hopeless. Afterward, I feel more admiration than gratitude.