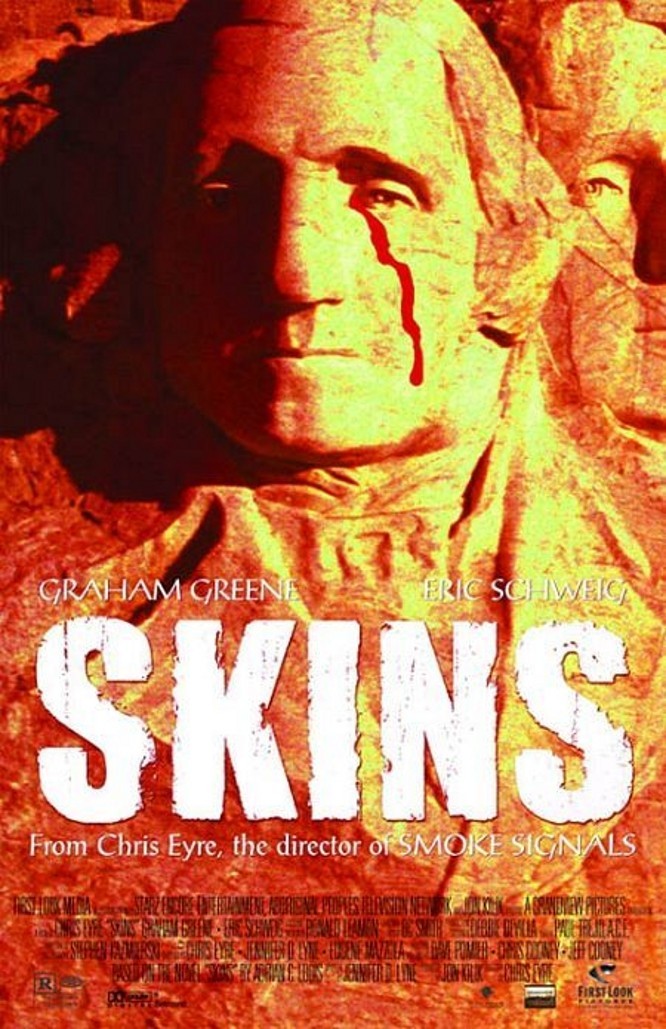

“Skins” tells the story of two brothers, both Sioux, one a cop, one an alcoholic “whose mind got short-circuited in Vietnam.” They live on the Pine Ridge reservation, in the shadow of Mount Rushmore and not far from the site of the massacre at Wounded Knee. America’s founding fathers were carved, the film informs us, into a mountain that was sacred to the Sioux, and that knowledge sets up a final scene of uncommon power.

The movie is almost brutal in its depiction of life at Pine Ridge, where alcoholism is nine times the national average and life expectancy 50 percent. Director Chris Eyre, whose previous film was the much-loved “Smoke Signals” (1998), has turned from comedy to tragedy and is unblinking in his portrait of a community where poverty and despair are daily realities.

Rudy Yellow Lodge (Eric Schweig), the policeman, is well-liked in a job that combines law enforcement with social work. His brother Mogie (Graham Greene) is the town drunk, but his tirades against society reveal the eloquence of a mind that still knows how to see injustice. Mogie and his buddy Verdell Weasel Tail (Gary Farmer) sit in the sun on the town’s main street, drinking and providing a running commentary that sometimes cuts too close to the truth.

Flashbacks show that both brothers were abused as children, by an alcoholic father. Mogie probably began life with more going for him, but Vietnam and drinking have flattened him, and it’s his kid brother who wears the uniform and draws the paycheck. Those facts are established fairly early, and we think we can foresee the movie’s general direction, when Eyre surprises us with a revelation about Rudy: He is a vigilante.

A man is beaten to death in an abandoned house. Rudy discovers the two shiftless kids who did it, disguises himself, and breaks their legs with a baseball bat. Angered by white-owned businesses across the reservation border that make big profits selling booze to the Indians on the day the welfare checks arrive, he torches one of the businesses–only to find he has endangered his brother’s life in the process. His protest, direct and angry, is as impotent as every other form of expression seems to be.

When “Skins” premiered at Sundance last January, Eyre was criticized by some for painting a negative portrait of his community. Justin Lin, whose “Better Luck Tomorrow” showed affluent Asian-American teenagers succeeding at a life of crime, was also attacked for not taking a more positive point of view. Recently the wonderful comedy “Barbershop” has been criticized because one character does a comic riff aimed at African-American icons.

In all three cases, the critics are dead wrong, because they would limit the artists in their community to impotent feel-good messages instead of applauding their freedom of expression. In all three cases, the critics are also tone-deaf, because they cannot distinguish what the movies depict from how they depict it. That is particularly true with some of the critics of “Barbershop,” who say they have not seen the film. If they did, the audience’s joyous laughter might help them understand the context of the controversial dialogue, and the way in which it is answered.

“Skins” is a portrait of a community almost without resources to save itself. We know from “Smoke Signals” that Eyre also sees another side to his people, but the anger and stark reality he uses here are potent weapons. The movie is not about a crime plot, not about whether Rudy gets caught, not about how things work out. It is about regret. Graham Greene achieves the difficult task of giving a touching performance even though his character is usually drunk, and it is the regret he expresses, to his son and to his brother, that carries the movie’s burden of sadness. To see this movie is to understand why the faces on Mount Rushmore are so painful and galling to the first Americans. The movie’s final image is haunting.