From the room he occupied for years in the old Cliff Dwellers’ Club atop Orchestra Hall, Louis Sullivan could have looked out his window and seen, with the aid of a time machine, Frank Gehry’s Pritzker Pavilion band shell in Millennium Park. The man who wrote “form follows function” would have contemplated the work of a man who seems to believe that form is function.

Although the band shell functions as a stage for performances, most of its visitors probably regard it first of all as sculpture. By the same token, Gehry’s most famous work, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, has been accused of one-upping the art inside. Certainly when I visited in 2001, the Giorgio Armani career retrospective on the third level was hard-pressed to hold its own against the building containing it.

“Logotecture,” one of Gehry’s critics calls the Chicago band shell. The charge is that Gehry, having designed some brilliant buildings, is now ripping himself off to provide one city after another with its very own Gehry. This is a cheap shot. Mies van der Rohe attempted as nearly as possible to do the same thing over and over again, only more elegantly. Is there an enormous difference between his residential high-rises at 860 and 880 Lake Shore Dr. and his IBM Building? No, but it’s not logotecture, and neither is Gehry. An architecture critic has the opportunity to travel widely and become jaded by many Gehry buildings. The average person regarding the band shell is looking at the only Gehry he or she will see in their lifetime.

Well, not quite the only: Gehry also designed the elegant bridge connecting Millennium Park with the gardens on the east side of Columbus Drive. One day as I was visiting the park, it occurred to me that if Anish Kapoor’s vast “Cloud Gate” has been universally renamed The Bean, then obviously Gehry’s bridge is The Snake. And what is the band shell? Stand at the south end of the lawn, notice the web of arches that enclose the space and carry the sound, and observe the shell crouching at the other end. The Spider, obviously.

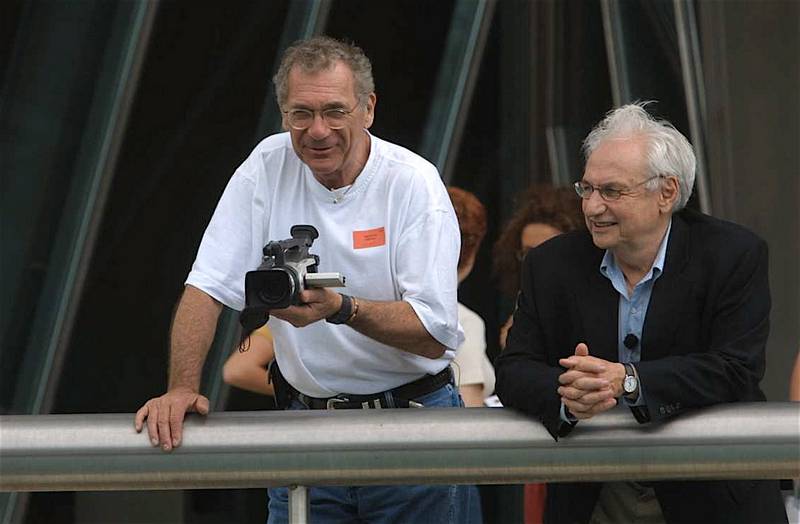

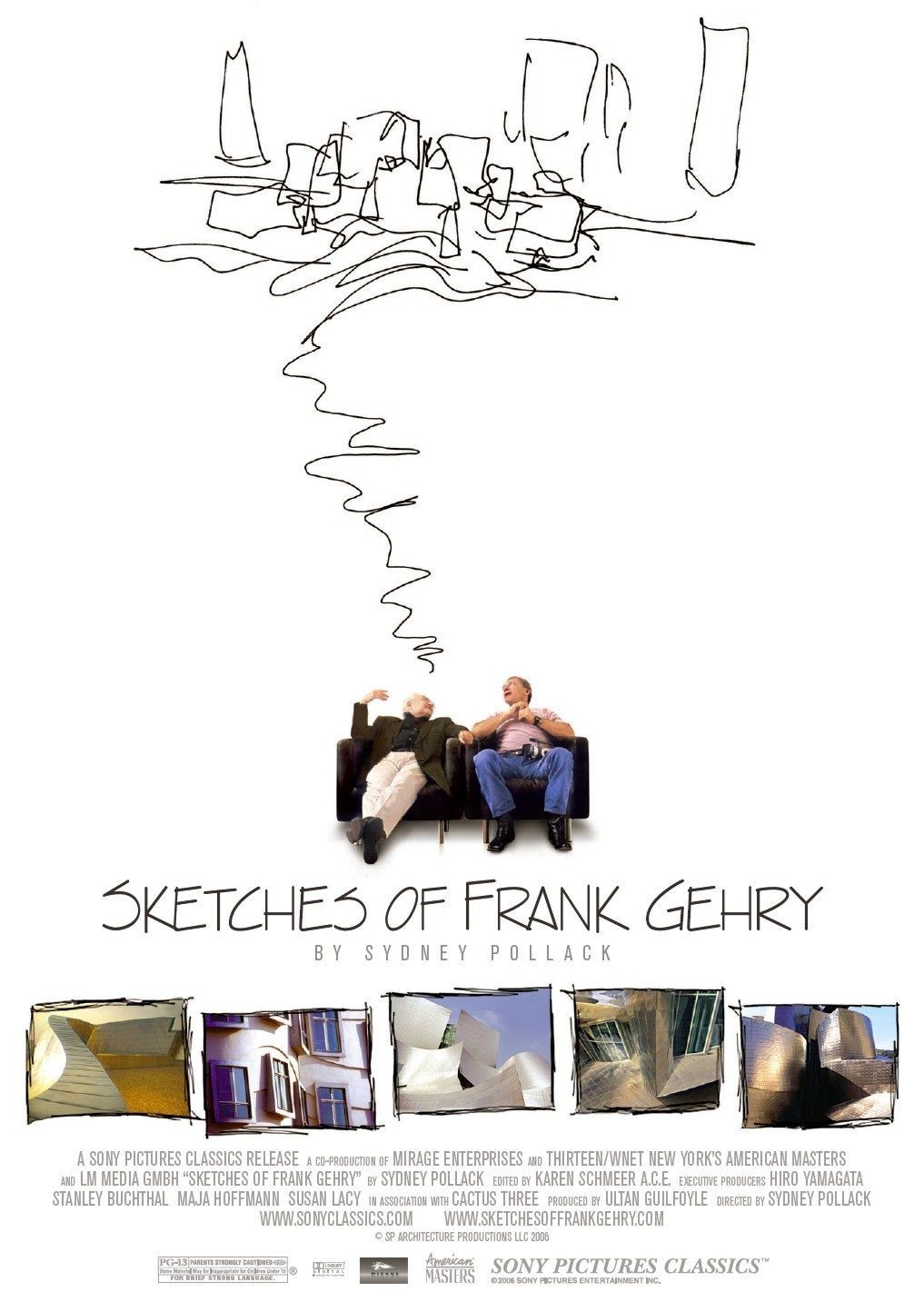

These musings are inspired by “Sketches of Frank Gehry,” an engaging documentary made by the Hollywood director Sydney Pollack (“Out Of Africa,” “Tootsie,” “The Way We Were“). Pollack is not usually a documentarian, and Gehry has never been documented; they were friends, and Gehry suggested Pollack might want to “do something.” The result is not a formal doc but an extended chat between two professionals who, as Pollack puts it, search for “a sliver of space in the commercial world where you can make a difference.”

Gehry did not begin by designing sculptural buildings. He takes Pollack to look at Santa Monica Place, his conventional 1984 shopping center at the end of the Third Street Mall in Santa Monica. Does Gehry like it? No. We meet his psychiatrist, Milton Wexler, authorized by Gehry to speak about a period in the 1980s when the architect made a breakthrough into his modern work; this process apparently involved, or perhaps even required, divorcing his first wife. All we learn about her from the film is that she pushed for her husband to change his name from Goldberg, to sidestep anti-Semitism. Since he then immediately told everyone “my real name is Goldberg,” this was less than perfectly functional, but we understand the form.

Gehry’s design process could be inspiring for a kindergarten student. First he doodles on sketch pads. A form emerges. He uses construction paper, scissors and tape to make a three-dimensional model from it. He plays with the model. Eventually, it looks about right. His assistants use computer modeling to work out the stresses and supports, and together with his team he works on the interior spaces. Gehry’s buildings are so complex that he believes they would have been impossible before computers (which he does not know how to operate). Certainly the math would have been daunting. Computers assure him that his cardboard fancies are structurally sound.

In this connection, I remember the first famous architect I met, Max Abramowitz. I was sent as a young reporter to interview him on the site of the University of Illinois Assembly Hall, the largest rim-supported building ever made. Seating 16,000 people in a circle, it had no interior supports, and was held together by 500 miles of steel cable wrapped around the rim where the top bowl rested on the bottom.

“Will this be your greatest achievement?” I asked the man who designed the United Nations headquarters.

“If it doesn’t fall down,” he said.

Because Pollack has his own clout and is not merely a supplicant at Gehry’s altar, he asks professional questions as his equal, sympathizes about big projects that seem to go wrong and offers insights (“Talent is liquefied trouble”). Because he is Pollack, and because he has Gehry’s blessing, he has access to the architect’s famous clients, like Michael Eisner, who commissioned the Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, and Dennis Hopper, who lives in a Gehry home in Santa Monica. He talks to the (late) great architect Philip Johnson, old and secure enough to praise a competitor.

There are also a few critics brought in to provide balance, although Pollack’s opinion is clear: Gehry is a genius. Having gazed upon the Guggenheim and the Disney and sat happily on the grass beneath the Spider’s web, I think so, too. Gehry helped to tempt modern architecture out of its well-behaved period.