This bare outline makes Rose seem like a monster, but the reality was much, much more complicated. Years earlier, in 1982, Flanagan had signed a contract giving Rose “total control over my mind and body.” They had a sadomasochistic relationship lasting 15 years. At the end she was not being cruel, so much as expressing her fear of losing him. It sounds cruel because she speaks in the terms they used to express their love.

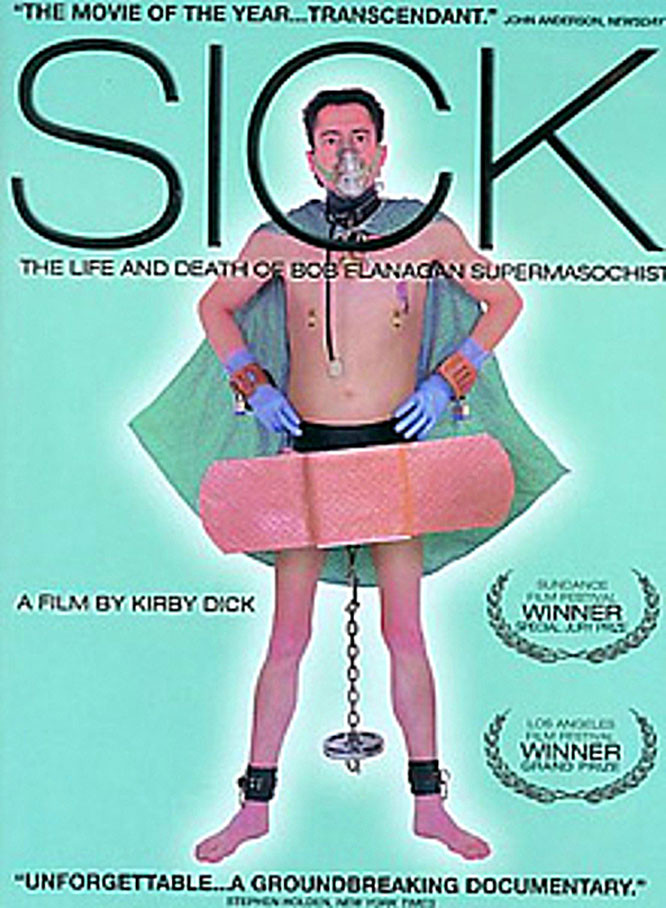

“Sick: The Life & Death of Bob Flanagan, Supermasochist” is one of the most agonizing films I have ever seen. It tells the story of a man who was born with cystic fibrosis, a disease that fills the lungs with thick, sticky mucus, so that breathing is hard and painful, and an early death is the prognosis. He was in pain all of his life, and in a gesture of defiance he fought the pain with more pain. With Sheree Rose as his partner, he became a performance artist, using his own body as a canvas for museum shows, gallery exhibits, lectures and performances. He was the literal embodiment of the joke about the man who liked to hit himself with a hammer because it felt so good when he stopped.

Flanagan’s masochism began early in life. He recalls forcing himself to sleep under an open window in the winter, and torturing himself by hanging suspended from his bedroom ceiling or the bathroom door (“My parents could never figure out why all the doors were off the jambs”). By the time he made it formal with Rose, he had already been a masochist for years. “Where was I?” his mother asks herself. “Did we only give him love when he was in pain? I don’t know. He was in pain so much of the time.” How do you develop a taste for sticking nails into yourself? His parents recall that as a small child he had pus drained from his lungs by needles; since he felt better afterward, perhaps he identified the pain with relief. Later it became a sort of defiant gesture. His father says, “He’s saying to God: `I’ll show you!’ ” In Rose he found a woman who was a true dominatrix, not just a kinky actress with bizarre costumes. He also found a life partner, and the closeness of their relationship seems frightening at times; they seemed to live inside each other’s minds.

What makes “Sick” bearable is the saving grace of humor. Apart from the pain he was born with and the pain he heaped on top of it, Bob Flanagan was a wry, witty, funny man who saw the irony of his own situation. We see video footage of his lectures, his songs, his poems. He takes one of those plastic “Visible Man” dolls they use in science class and modifies it to illustrate his own special case. As he jokes, kids himself and makes puns about pain, we are aware of the plastic tubes leading into his nose: oxygen, from a canister he carries everywhere.

We are a little surprised to discover that from 1973 to 1995 he was a counselor at a summer camp for kids with cystic fibrosis, and around the campfire we hear him singing his version of a Bob Dylan song, “Forever Lung.” He was “scheduled” to die as a child, but lived until 42 (two of his sisters died of the disease). He was a role model for CF survivors. We meet a 17-year-old Toronto girl named Sara who has cystic fibrosis and tells the Make-a-Wish Foundation that her wish is to meet Bob Flanagan. She does. How does she deal with his sex life? “Bondage. I can relate to that. Being able to control SOMEthing … .” Flanagan and Rose collaborated on this film with the documentarian Kirby Dick. It is a last testament. Flanagan was very sick when the filming began, and died in January, 1996, almost literally on camera. We see and hear him gasping for his last breaths. If that seems heartless, reflect on his (unrealized) plans for a final artwork: “I want a wealthy collector to finance an installation in which a video camera will be placed in the coffin with my body, connected to a screen on the wall, and whenever he wants to, the patron can see how I’m coming along.” There are scenes in “Sick” that forced me to look away. But the scenes I did watch were, if anything, more painful. At the end, as Bob fights for breath and Sheree weeps and cares for him, what we are seeing is a couple who had something, however bizarre, that gave them the roles they preferred, and mutual reassurance. Now death is taking it all away.

No one can say that Bob Flanagan, after his fashion and in his own way, did not fight back.