At Toys in Babeland, a sex shop in lower Manhattan, sales increased 30 percent in the wake of 9/11, according to the New York Observer. A year after 9/11, the number of babies born in New York hospitals was up 20 percent.

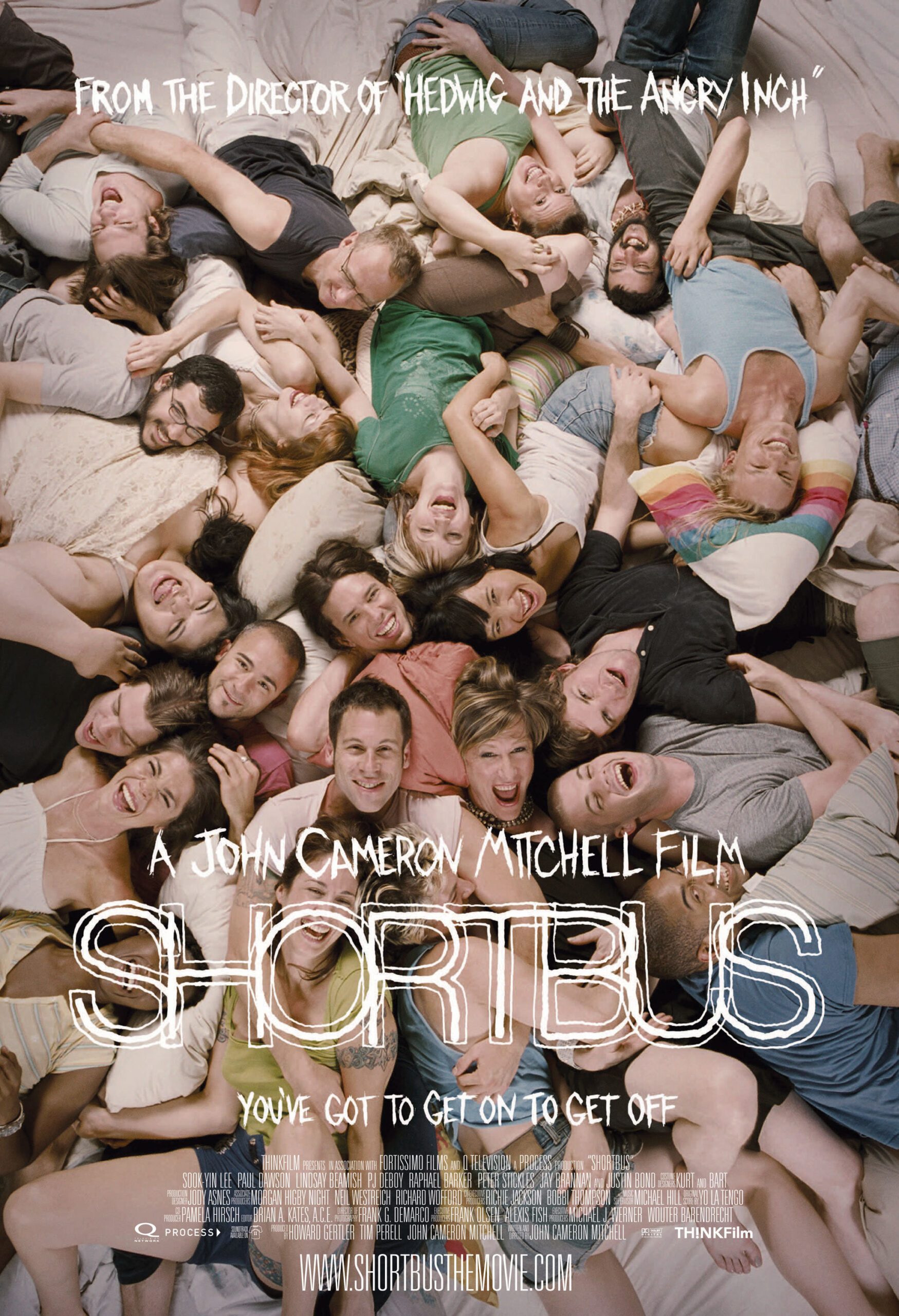

These statistics form the background for John Cameron Mitchell’s enchanting “Shortbus,” the most unexpectedly honest and moving American feature film about 9/11 yet. And by far the funniest.

No, this is not a gripping docudrama, extrapolated from eyewitness accounts and official investigative findings, pumped full of Hollywood dramatic speculation and designed to elevate real-life heroism into the realm of pop-culture super-myth, like “United 93” and “World Trade Center.” Instead, “Shortbus” takes place entirely in a fantasy post-9/11 New York City (played in the film by an ingenious handcrafted miniature), an interstitial dream in the chasm between that black day in September 2001 and the blackout of August 2003. In this ephemeral temporal-geographical metropolis, a lot of people engage in a lot of sex for a lot of reasons. And not to make you feel better about their valor, but simply because they’re human beings who are still alive.

Some of these Sodomitic Gothamites seek post-traumatic sexual healing in the aftermath of so much disjunction and death so close to home. Some are looking for the Big O, or the Little Death, a way to lose themselves — their fears, their pain — in a larger psycho-sexual release. And some are searching for someone or something to make themselves complete, the physical and emotional “other half” depicted in Mitchell’s previous movie musical, “Hedwig And The Angry Inch“:

But I could swear by your expression

That the pain down in your soul

Was the same as the one down in mine….So we wrapped our arms around each other,

Trying to shove ourselves back together.

“Shortbus” is full of wounded, fractured people trying to shove themselves back together. Just as the genitally stunted Hedwig personified sex as the Great Divide, the new Berlin Wall that was also a bridge (“Without me right in the middle, babe, you would be nothing at all”), the characters in “Shortbus” focus on sex as a way of getting through to each other, and getting in touch with themselves. It’s a gleefully randy romantic roundelay, in the tradition of Max Ophuls’ serially sexual French comedy “La Ronde” (1950). Polymorphously pornographic, sure; but it doesn’t feel the slightest bit obscene. And that’s a neat trick.

The camera soars over a colorful model of New York City, a dazzling imaginative creation suggesting both artistic sophistication and handmade naivete: The city as a brilliant child’s ultimate Play-Doh project. We swoop into people’s windows for a passing glimpse into their lives, before taking off once again to alight on someone else’s sill. At the lower tip of Manhattan, we see a burnt red scar with two square gouges. We pull up and… we’re overlooking the real Ground Zero from a window decorated with dildos. A downtown dominatrix, her masochistic client tied to the bed, grumpily goes through the workaday motions of her unfulfilling job, which climaxes in an artsy eruption of Abstract Expressionism.

Jamie (PJ DeBoy), a former child star who was once known as the only white kid in a black TV sitcom family (“I’m an albino!” was his dyn-o-mite catch phrase), frets that his boyfriend (Paul Dawson), also named Jamie but now going by James in order to get a little distance from his needy partner, is withdrawing emotionally. James, a video artist, spends a lot of time alone, crying, and trying to fellate himself on camera. For couples counseling, the Jamies are seeing Sofia (Sook-Yin Lee), who is herself having sexual fulfillment issues with her husband Rob (Raphael Barker).

All of them attend a freewheelin’ orgiastic party/salon called Shortbus (hosted by Justin Bond, the Kiki half of the performance duo Kiki and Herb), where the sexually gifted and challenged gather to co-mingle in every way imaginable. Sofia befriends Severin (Lindsay Beamish), the aforementioned dour dominatrix, and each clumsily assists the other in her quest for greater intimacy. The Jamies take in a sweet-faced, lovelorn kid named Ceth (Jay Brannan) to act as a bridge and buffer between them.

Aboard the voyeuristic celebration of carnality that is “Shortbus,” sex isn’t a metaphor for something else; everything else is a metaphor for sex, the lens (camera? telescope?) through which this porno-topia is viewed and realized.

Mitchell, who appears only for a flash in an orgy scene, developed the stories and characters (in a process that sounds akin to Mike Leigh’s methodology) with the help of his cast, who were chosen for their willingness to open up and engage in on-camera sex of every stripe. That they do. But when was the last time sex in a movie actually made you (intentionally) laugh out loud? Here’s a woman who tries so hard to have an orgasm that each strenuous effort puts her that much further from her goal. Here are three intertwined naked men performing a pornographic Broadway Melody version of “The Star Spangled Banner” using orifices that would have sent Francis Scott squealing for an even higher Key. Some of these scenes deserve their own ribald entries in Playboy’s “Unabashed Dictionary.”

Like its utopian fantasy miniature, “Shortbus” is a sweet, tender, playful pleasure — so much so that, when an old man who identifies himself as the former mayor says that New York is where people come seeking forgiveness, you actually believe him, even though the words “New York” and “forgiveness” have probably never been uttered in the same sentence before. And by the time Justin Bond’s bullhorn baritone croons “Everybody Gets It In the End,” the thin characterizations and soapy sitcom plot contrivances melt away in a cleansing, melancholy humor, and you notice that something quite magical and moving — and healing — is taking place, for real, right before your eyes.