In retrospect, it seems hard to believe that director Zhang Yimou didn’t make his first wuxia-influenced historical action film until two decades into his career, after a string of intimate yet visually striking dramas. But the double-hit of “Hero” and “House of Flying Daggers” (both released in 2004 in North America) reinvented him as one of cinema’s foremost directors of intricate mayhem, designed, lit, and edited with such care as to make the cliche comparison between action pictures and musicals feel not just fresh, but deep. Zhang never quite climbed to that peak of global crossover again. His family drama “Coming Home” and his remake of the Coen brothers’ “Blood Simple,” titled “A Woman, a Gun, and a Noodle Shop” were more intriguing than compelling, and his recent big-budget international coproductions (“The Flowers of War” and “The Great Wall“) felt more like ambitious financial undertakings than artistic ones.

“Shadow,” a tale of court intrigue sprinkled with giddy duels and scenes of armored soldiers clashing, isn’t quite a return to form; Zhang’s first two action pictures were so nearly miraculous that it’s hard to imagine them being equalled. But it’s filled with so many remarkable images, particularly in its middle section, that fans of palace intrigue and metaphorically ripe violence will find plenty to like.

Be warned going in that the first half-hour of “Shadow” is a pretty laborious setup: mostly characters walking in and out of rooms and announcing how they are related to each other, in terms of both bloodline and power dynamics. King of Pei (Zhang Kai), a snippy little despot, is still angry that a neighboring city that used to belong to his kingdom is now in the control of a general named Yang (Hu Jun), who won it in a duel. The king wants to get the city back somehow, or at least gain a foothold in it, so he offers his sister Princess Qingping (Guan Xiaotong) as a wife for Yang’s son, only to be insulted by a counteroffer of making her a concubine and presenting a ceremonial dagger as a gift. To further complicate things, the king’s Commander (Chinese star Deng Chao) just returned from challenging the general to a duel without authorization from higher up.

And wouldn’t you know it: the Commander isn’t even really the commander. He’s a double named Jing (also played by Chao) who’s been trained from childhood to take over for the Commander if circumstances demand it. And they do: the Commander is hiding in a secret chamber beneath the royal city, recovering from a grievous wound he sustained in the aforementioned duel with the general that resulted in the other city being lost. The only person who knows about the subterfuge is the Commander’s wife Madam (Sun Li), who quite naturally starts to develop feelings for her husband’s double.

The expository stuff at the front of the film isn’t inherently awful—it’s necessary to understand the large-scale violence that dominates the rest of the story, and the cast does a fine job of balancing simplicity and stylization with psychology. But aesthetically, it doesn’t begin to hint at the splendors that await, and it promises a richness of characterization (particularly among the secondary players) that the movie, which is often pitched at the level of a brilliantly designed video game, doesn’t quite deliver. (Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa—a major influence on Zhang whose works include “Kagemusha,” another historical action/military movie with a secret double at its heart—was better at making the talky bits exciting, too.)

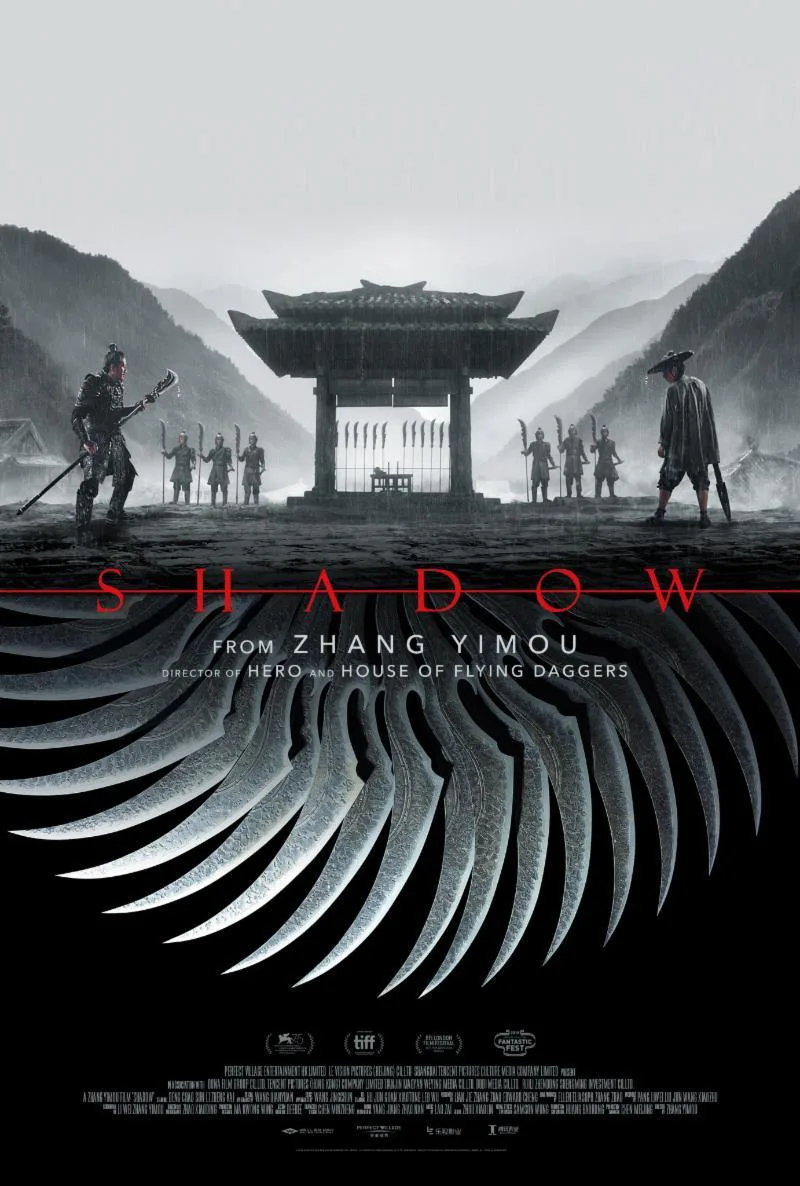

Once the action kicks in, though, “Shadow” is on rails. Zhang, co-screenwriter Li Wei, cinematographer Zhao Xiaoding, production designer Horace Ma, and costumer Chen Minzheng work in seemingly perfect harmony to create a visual scheme that the director has said is based on the brush techniques of Chinese painting and calligraphy. The world they present would read as black and white (and grey) were it not for the flesh tones of the actors’ faces and bodies, and the voluptuous dark blood that splatters the screen whenever swords, knives, arrows, and crossbow bolts start to fly.

It’s impossible to understate how thrilling “Shadow” is during its middle section, when Zhang is crosscutting between the increasingly knotty intrigue in two cities, a second duel that we’ve been building toward for 45 minutes, the romantic tension between the Commander and his wife and his double, and a large-scale military action that’s intended to retake a city.

Confidently showy in a manner that evokes the most dazzling sequences in Zhang’s action classics, the movie takes symbolism that might seem simplistic and overdone (such as the prominent display of the yin and yang symbol in both dialogue and sets) and makes them feel organic to the tale, not in the manner of a novel or play, but an opera or art installation or graphic novel. The true yin and yang of the film is its expressive balance of masculine and feminine elements of design and choreography, especially as they’re expressed in combat.

The bluntly macho shapes of swords and halberds (as swung and thrust by confident, scowling men) are contrasted against razor-edged umbrella weapons deployed with deliberately feminine motions (by men as well as women; when combatants get in touch with their feminine side, the movie suggests, they’re able to achieve their goals in different, often surprising ways). The bearers of these killer umbrellas practically waltz into combat with them, hips swaying demurely, then use them as toboggans to carry them down steep, muddy hills. A sequence where an umbrella battalion tries to retake an occupied thoroughfare during a rainstorm attains a peak of controlled madness reminiscent of some of the wildest scenes in “Kung Fu Hustle,” a classic that wasn’t afraid to go full Looney Tunes. When Zhang crosscuts between a duel on a rainy mountaintop and a zither battle happening in a subterranean chamber, with the zither music providing the sequence’s melody and the clanging blades percussion, the essence of action cinema is distilled.

When the movie decelerates in its third act, the better to resolve all the plot particulars laid out in the first section, it’s hard not to feel let down. It’s like that feeling where you disembark a roller coaster and can still feel vertigo in your belly. But “Shadow” is so masterful during its wilder sections that a bit of tedium eventually seems a rather small price to pay. Zhang’s action is so magnificently imagined—not just in the bigger, more brazen touches, but in grace notes, like the way a weapon’s gory blade grinds as it’s dragged over rainy cobblestones, trailing plumes of muck and blood—that it shames the current industry norm as expressed in Marvel and DC films and most action thrillers post-Jason Bourne, which consist mainly of swinging the camera around and cutting as fast as possible, often (it seems) to disguise the fact that the performers aren’t all that graceful, and the director doesn’t really have a style, just money.

Zhang’s best work here is old-school craft, practiced with the latest filmmaking equipment and processes. The movie knows not just what do to technically, but how to make it resonate with the story and themes, and how to make images sing and dance. In a time of diminished expectations for big screen spectacle, and “content” replacing cinema, it takes a master to remind us of what’s been lost.