As many Americans know, Southerners have a passionate attachment to their land, their guns, their hunting dogs and their orneriest eccentrics. The trick about conveying any of these things—or in the case of Annette Haywood-Carter’s “Savannah,” all of them—to an audience unfamiliar with the particulars being rendered is to find ways to make them dramatically credible and emotionally resonant. Failing that, as “Savannah” does, means fashioning a movie that’s essentially only of local interest.

The locality in question, you may have guessed, is a certain city in coastal Georgia. But since the movie, which takes place in the early 20th century, doesn’t tell us much about the town—as “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil,” say, does—and its hero’s feelings about it seem decidedly ambivalent, a viewer might suspect that the odd title actually refers to the Savannah River, the one place where that hero does seem at home.

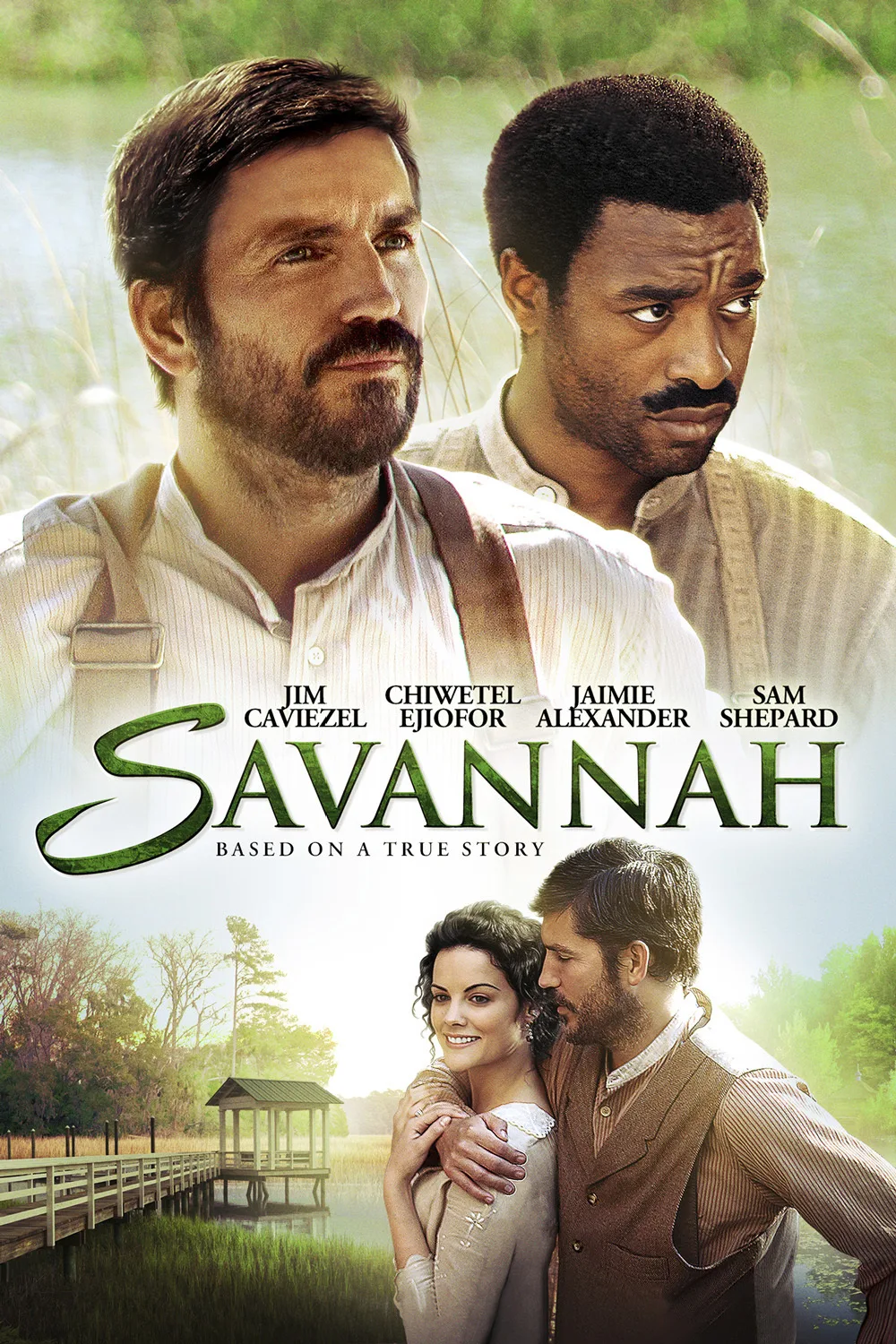

His name is Ward Allen (Jim Caviezel), and the film’s story is supposedly true, drawn from a book of anecdotes about a man evidently regarded by his contemporaries as a mythically colorful contrarian. Born in Savannah in 1856, Allen attended Oxford University where he imbibed the beauties of Shakespeare and the classics, but on returning home, he decided that neither the professions nor gentleman-farming suited his nature. So he devoted his life to duck hunting, in the company of his sidekick Christmas Moultrie (Chiwetel Ejiofor), a former slave.

Allen’s story is narrated by the 95-year-old Moultrie (scenes that involve some terrible old-age makeup for Ejiofor), who begins with an anecdote that’s later repeated, as if it’s especially wonderful or illuminating. In it, young Allen, visiting Russia, has half his moustache shaved off by a barber; enraged, he tries to kill the man but is prevented by three Russians. The viewer can’t help but wonder why this scene is in the movie at all, as we hear nothing else about Allen in Russia, about his devotion to his moustache, or about why the barber gives him such a bad shave. One suspects that Allen’s admirers simply found the tale wildly funny. But in the movie it only serves to suggest—inadvertently—that the man was boorishly vain and violence-prone.

“Savannah” is rife with such unintended implications. Allen’s big problem in life, as the film tells it, is that the law puts limits on duck hunting, and he can’t resist violating them. This leads to several scenes in the courtroom of an indulgent judge (Hal Holbrook), who shares what seems to be Savannah’s universal bemusement with Allen’s antics and verbosity and usually lets him off with mere wrist-slappings. Somehow, these appeals to the jollity of law-breaking come off as forced and inane. (Absurdly, the film ends with a title telling us that Allen was “a champion of common sense game laws, fair to both hunter and game.” It doesn’t explain how ducks might regard being killed off-season or in excessive numbers as “fair.”)

In the romantic department, the film depicts Allen’s ill-fated relationship with Lucy Stubbs (Jaimie Alexander), a spirited high-society lass whose father (Sam Shepard) is rightly suspicious of Ward’s suitability as marriage material. Even Allen tries to disabuse her of the romantic notion that he’s some kind of Southern-fried Thoreau, but she plunges ahead anyway, and eventually pays the price for her impetuousness. One night when he comes home drunk and she challenges him, he shoots the eyes out of her oil portrait, a violation that actually lands him in jail. Later, Lucy loses their first-born in childbirth, then spirals into a deep depression that ends in her institutionalization.

The latter event suggests a tragic dimension to Allen’s story, but the film isn’t interested in plumbing such depths. It’s equally incurious about the other big relationship in Allen’s life, the one with Christmas Moultrie. Its portrait of the black man gives us nothing more or less than a faithful retainer, that stereotype from centuries of (white) Southern nostalgia. No doubt the film wants to show that such easy, brotherly familiarity between black and white was how “it really was” in the South. That’s perhaps true to an extent, but it doesn’t excuse simply ignoring other, less flattering things Moultrie may have felt—like an awareness of the humiliations endemic to black life in Jim Crow Georgia.

With its top-drawer cast and plush production values, “Savannah” looks like it must’ve cost many millions of dollars to make, which is noteworthy for a film that seems to have no hope or competing against major-studio fare or of gaining traction on the indie circuit. How does such an expensive film get made when it seems destined not to recoup? Perhaps some of the answer to that lies in the fact that Executive Producer John Cay, whose father wrote the book of anecdotes on which the film is based, is a former Vice Chairman of Wells Fargo Services, “the third largest insurance brokerage firm in the United States.” If Mr. Cay was out to make a kind of home movie for the folks in Savannah, he evidently had the wherewithal to do it. That’s the kind of extravagant gesture that Ward Allen himself might have applauded.