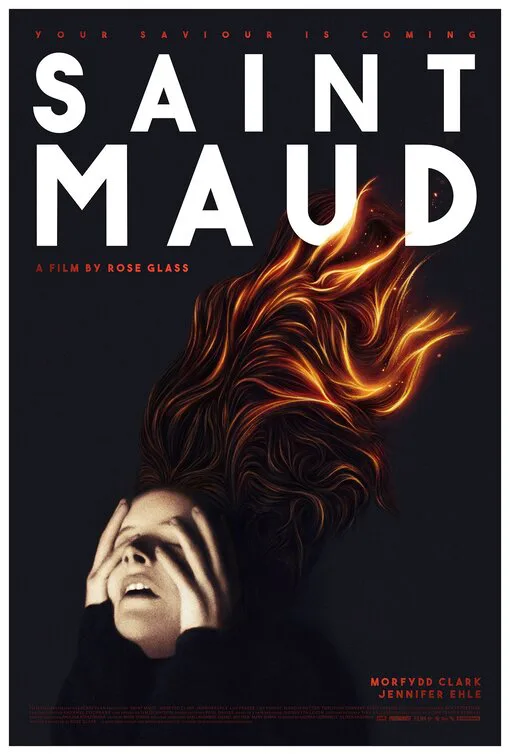

“Forgive my impatience, but I hope you will reveal your plan for me soon. I can’t shake the feeling that you must have saved me for something greater than this.” This is how Maud (Morfydd Clark), a home nurse living in the seashore town of Scarborough, talks to God. Her tone is intimate, practical, chatty, as though He’s sitting in the next room. When things start to go wrong, however, her voice takes on a distinctly irritable tone. God isn’t holding up His end of the bargain. “I can’t help but feel an act of spite has occurred,” Maud scolds God. Maud is a recent convert to Roman Catholicism, and glows with the evangelical zeal of her brand-new faith. She wants everyone to experience the bliss she’s experienced. “Saint Maud,” an eerie and disturbing first film from writer/director Rose Glass, shows Maud’s first attempt to “save” another soul, and the cracks that open up underneath Maud’s feet in the process. Is Maud touched by the divine? Or is she going mad? Is there a difference?

“Saint Maud” stays very close to Maud’s point of view. She is in every scene. We see events through her eyes. The glimpses we get of other people’s sometimes alarmed responses to her are important moments of outside perspectives, but Maud is our only entry into the story. This makes for some very tough but rewarding viewing. Although the film has much in common with other religious-based horror films, and is often quite terrifying in its own right, “Saint Maud” is mostly interested in the experiential realities of its central character, and Clark is so deeply in touch with Maud’s shattered psyche it’s impossible to look away from her. It’s thrilling to meet a character where you have no idea what she will do from one moment to the next.

Maud gets a new gig as home “carer” for Amanda (Jennifer Ehle), a famous dancer and choreographer who has retired to the seashore for the final months of her life. Amanda surrounds herself with evidence of her old glory: posters of her dance recitals, her costumes, makeup, outrageous jewelry. She’s in the midst of one final romantic fling, with Carol, a young woman she met online (Lily Frazer). The ascetic Maud, peeking through doorways and down dark halls, is worried about all of this. Amanda needs to be “saved” immediately.

At first it seems that Amanda might be open to the succor Maud’s preaching has to offer. But maybe Amanda is just playing along, or, worse, making fun of Maud’s fervor. And first “Saint Maud” feels like it is about a power struggle between Maud and Carol for the heart and/or soul of Amanda. But “Saint Maud” takes a turn. This story is not about Maud and Amanda, not really. It is about Maud alone, and what happens to Maud when Amanda rejects conversion in a very public way (i.e. tells Maud to back off). Maud’s deterioration is rapid. With each scene, each moment, more and more of Maud is revealed, who she was pre-conversion, who she is now. The center cannot hold. There is no center.

Maud’s face is serious and intense, and her hair hangs in long curtains on either side of her face. She moves through the busy resort streets like a wraith, existing on another plane, floating above her body in reveries of bliss, transcendence, ecstasy. How to maintain that state is a constant struggle. She puts nails through the soles of her shoes and slowly walks the pier, blood seeping out onto the ground, her face blazing with pain and ecstasy. You’ve heard of the “pebble in the shoe,” but pebbles aren’t enough for Maud: she needs nails! She puts hard corn kernels on the floor and kneels on them to pray. When she senses God’s presence, her face contorts involuntarily into an open-mouthed almost frozen gaze of ecstasy, more like an orgasm than anything else (historically, those lines have always been blurred). Maud’s backstory is mostly obscured. We don’t know how she came to be “saved,” but there is an extremely revealing sequence where Maud “backslides” into her former ways. This still doesn’t provide any easy explanation.

It’s exciting when newcomers like Glass arrive with a fully-fleshed-out and confidently executed vision, particularly when the vision is eccentric, difficult, and strange. This story has been told before. It’s in a continuum of stories of religious mortification, obsession, and torment. But “Saint Maud” comes with the stamp of its creator and shivers with fresh possibilities. By keeping the film a character study—as opposed to a plot-driven story of an avenging angel/demon—”Saint Maud” is less about the religion, and more about Maud’s existential loneliness (alone-ness, more like), her isolation, the dangers of being so cut off from humanity. The film has much in common with “Taxi Driver,” “Carrie,” and “First Reformed,” and it has a similar mood of inevitability and dread. Newcomer Adam Bzowski’s score—aligned with Maud’s subjective experience—is deeply unnerving, as is the sound design by Paul Davies, which further traps us in Maud’s point of view.

This is an independent film with a small budget, and Glass works extremely well within these parameters to create a murky and ominous mood. Glass uses the location of Amanda’s house to great effect, reveling in creepy moments of stillness, where the halls and stairways yawn around the quivering intense young nurse. The wallpaper is Victorian-busy, as are the floor tiles. The color scheme is very controlled, with an almost underwater gleam, greenish and dark, light struggling to make it through the thick mottled windows. Liquid is an ongoing motif, dripping from faucets, rolling in from the ocean, bubbling on the stove—greens and reds, soapy water down the drain, a strange cyclone suddenly erupting in a glass of beer. Reality is unpredictable seen through Maud’s sleep-deprived eyes.

Clark’s performance is central. Maud is most alarming when she is trying to be “normal,” when she attempts to be social. Nothing “comes off” right. People back away. Some of the scenes call to mind Travis Bickle in “Taxi Driver,” trying to talk to Peter Boyle or the other taxi drivers. It is now impossible to hide his true nature from others. Maud is the epitome of “too much.” In one scene, she smiles at people sitting at the next table in a pub, and they recoil a little bit. That girl … why is she staring at us? Why is she smiling like that? What is wrong with her?

Now in select theaters.