Dayton O. Hyde has accomplished so much and enjoyed such a wide range of experiences over his 88 years, it’s as if he’s lived several lives.

He’s an Army veteran who fought in World War II. He’s a cowboy who went to college, studying English at the University of California while also performing as a bullfighter in the late 1940s. He’s written over 20 books, his latest a collection of poetry. He’s a friend to the Native American people, joining members of the Lakota tribe as they perform their Sundance ritual annually on his ranch.

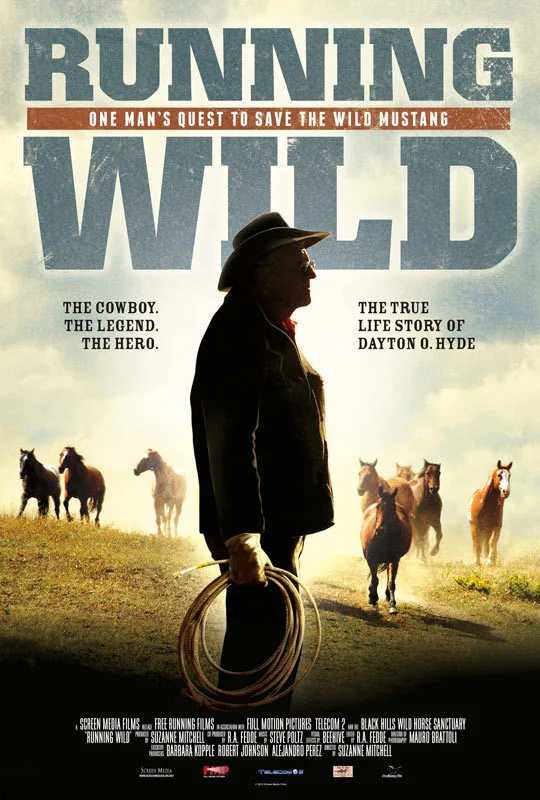

But Hyde is best known as a conservationist and fierce protector of wildlife, especially horses, as director Suzanne Mitchell chronicles in her documentary “Running Wild: The Life of Dayton O. Hyde.” Since 1988, Hyde has operated the Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary in South Dakota, a place where hundreds of mustangs can roam free over 12,000 acres rather than being rounded up.

Having grown up with animals, Hyde was heartbroken by the cruel treatment he witnessed as helicopters swarmed overheard to scoop up these majestic creatures and stick them in holding pens. Finding a home for wild horses and fighting for it has taken a toll on him, personally and financially, but it’s clearly his great passion.

The phrase “Renaissance man” gets tossed around a lot but in Hyde’s case, it really is true. He’s a fascinating guy, a romantic throwback to a lost time, modest and rambling in his lanky, 6-foot-5 frame.

Mitchell’s documentary is modest and rambling, too—perhaps too much so. Her film, which has been more than a decade in the making, features some lovely imagery of both awe-inspiring natural sprawl and moving intimate moments. Her account of the birth of a calf is especially beautiful and riveting.

But her pacing can be painfully languid, to the point of being nap-inducing. And having Hyde and members of his family read long passages from his books in voiceover—much of which comes in the form of a garbled drone—certainly doesn’t liven things up.

“Running Wild” also grows a bit repetitive, with Mitchell showing the same photos or footage several times, or Hyde musing on the same theme several times in slightly different ways. Volunteers and visitors at the sanctuary rhapsodize about what a magical place it is, something that should be obvious without telling us over and over again.

Hyde’s story seems like a better fit for long-form television journalism—a feature on “CBS Sunday Morning,” perhaps. Mitchell herself first became acquainted with Hyde while working on a TV segment about him and felt like he deserved his own documentary feature. She was obviously moved by him—his hard work and love of the land with very little pay—and she wants us to be moved, as well.

She has some surprises in store for us—the way certain relationships evolved throughout Hyde’s life, for example. People who have suffered great personal loss in their lives come to the ranch and find healing, which brings a jolt of pure emotion to the film. And Hyde himself is willing to be candid about his shortcomings as a husband and parent, acknowledging wistfully: “I think the ranch was a better father to the kids than I was.”

But then just when Mitchell seems to have found her groove, “Running Wild” becomes an entirely different film about 10-15 minutes before it ends. It veers off into another direction, skimming the surface of Hyde’s battle against the proposed uranium mining that would occur upriver from his sanctuary, potentially polluting the surrounding water and land.

At 88, Hyde is clearly up for the fight. And Mitchell’s right: He does deserve his own documentary feature. But this might not have been it.