Look at you. You’re 5-foot-nothin’ and you weigh a hundred and nothin’, and with hardly a speck of athletic ability.

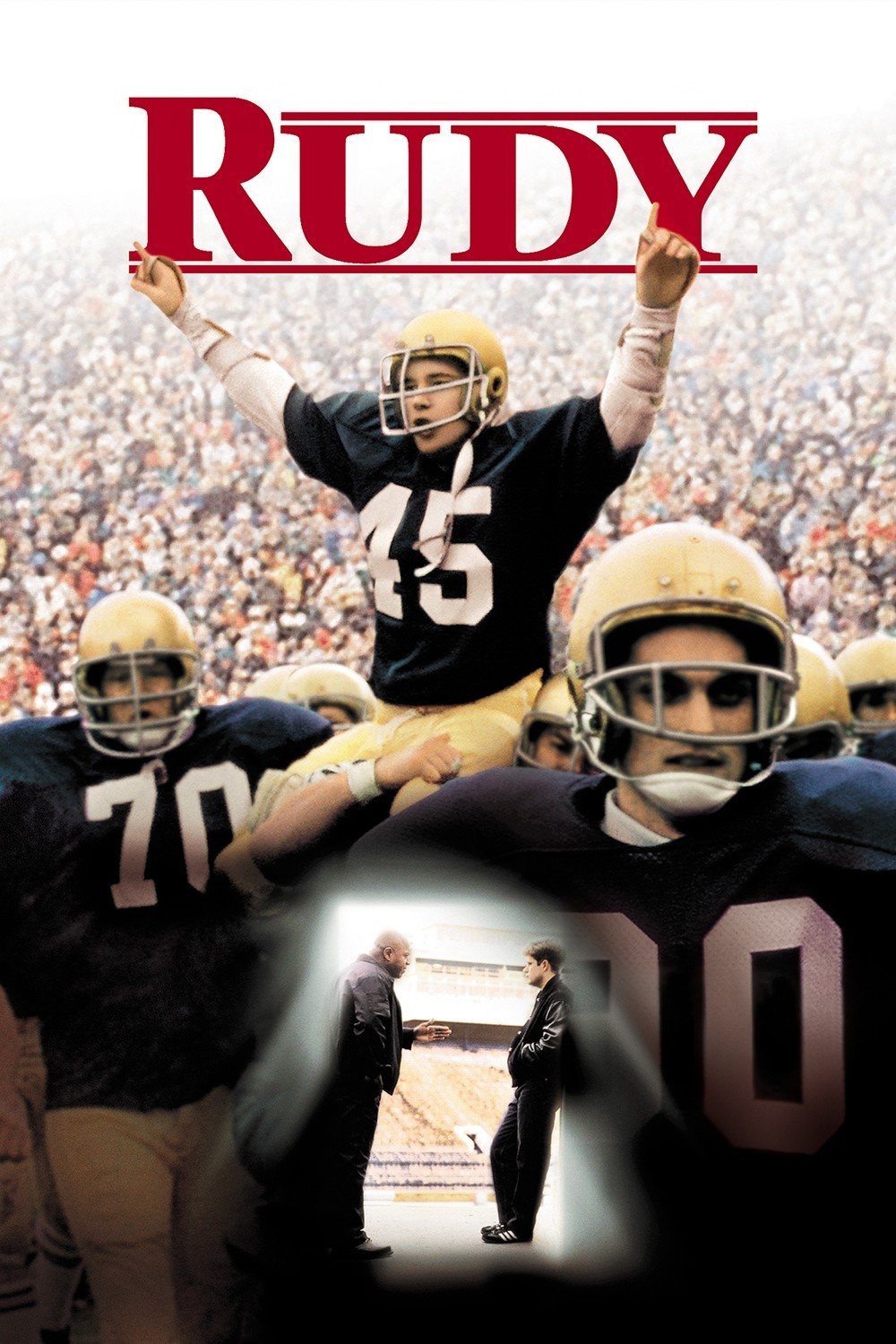

So says Fortune, a groundskeeper at the Notre Dame stadium, to Daniel “Rudy” Ruettiger Jr., whose dream is to play for the Fighting Irish. Rudy is not insane. He doesn’t expect to start. It would fulfill his lifetime dream simply to wear the uniform and get on the field for one play during the regular season, and get his name in the tiniest print in the school archives.

Almost everyone except Fortune thinks his dream is foolish.

Rudy comes from a working-class family in Joliet, where his father (Ned Beatty) joins his family, his teachers, his neighbors and just about everybody else in assuring him that he lacks not only the brawn but also the brains to make it into a top school like Notre Dame.

But Rudy persists. And although his story reads, in outline, like an anthology of cliches from countless old rags-to-riches sports movies, “Rudy” persists, too. It has a freshness and an earnestness that gets us involved, and by the end of the film we accept Rudy’s dream as more than simply sports sentiment. It’s a small but powerful illustration of the human spirit.

The movie was directed by David Anspaugh, who directed another great Indiana sports movie, “Hoosiers,” in 1986. Both films show an attention to detail, and a preference for close observation of the characters rather than sweeping sports sentiment. In “Rudy,” Anspaugh finds a serious, affecting performance by Sean Astin, the erstwhile teen idol, as a quiet, determined kid who knows he doesn’t have all the brains in the world, but is determined to do the best he can with the hand he was dealt.

To start with, he can’t get into Notre Dame. He doesn’t have the grades. But he’s accepted across the street at Holy Cross, where an understanding priest (the benevolent Robert Prosky) offers advice and encouragement. Finally Rudy is accepted by Notre Dame, one of the few remaining big football schools that still has tryouts for “walk-ons” – kids without starring high school careers or athletic scholarships.

It’s the mid-1970s. The Notre Dame coach is Ara Parseghian (Jason Miller). He doesn’t know what to make of this squirt who is happy to play on a practice team and offer his body up week after week so that the big Irish linemen can batter and bruise him on their way to a Saturday victory. Rudy isn’t really even good enough to be the lowliest sub, but he has great heart (something that is observed perhaps a little too often in the dialogue).

The movie is not cluttered up with extraneous subplots. A hometown girlfriend (Lili Taylor) is left behind, and for four years Rudy turns into a grind, studying nonstop to make his grades, and sometimes sleeping on a cot in the groundskeeper’s room because he doesn’t have money for rent. His father continues to think he’s crazy. But Rudy shows him.

Underdog movies are a durable genre and never go out of style. They’re fairly predictable, in the sense that few movie underdogs ever lose in the big last scene. The notion is enormously appealing, however, because everyone can identify in one way or another.

In “Rudy,” Astin’s performance is so self-effacing, so focused and low-key, that we lose sight of the underdog formula and begin to focus on this dogged kid who won’t quit. And the last big scene is an emotional powerhouse, just the way it’s supposed to be.