In 1997, on the first of several visits to Iran to investigate its cinema, I met a smart, genial young Iranian-Canadian filmmaker and journalist named Maziar Bahari. We kept in occasional touch thereafter and I followed his reporting on Iran in Newsweek, and was also impressed by his filmmaking, especially a chilling documentary called “Along Came a Spider,” about an unapologetic Iranian serial killer who preyed on prostitutes.

In 2009, after the learning the disturbing news that Bahari had been arrested while covering the massive unrest that followed Iran’s contested presidential election, I was shocked to see footage of him on television confessing to being a foreign spy and participating in a nefarious plot to destabilize Iran by the West. Maziar’s tense, drawn expression as well as his absurd words made it clear that this was a coerced statement, but what, I wondered, could have brought him to this point?

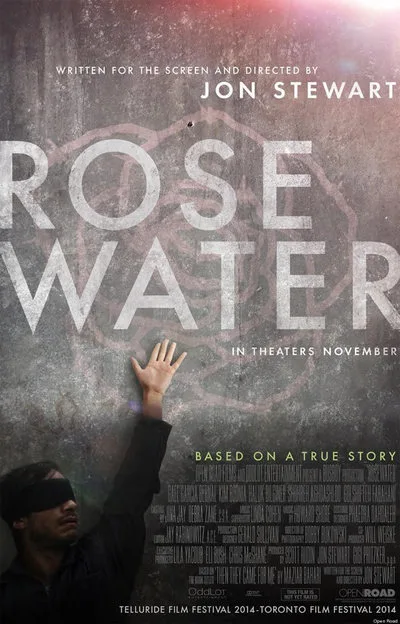

The answer to that is provided in “Rosewater,” the gripping, intelligent directorial debut of TV personality Jon Stewart, who also wrote the screenplay, based on Bahari’s post-prison memoir, “Then They Came For Me.”

The connection between Bahari’s story and Stewart’s “The Daily Show” is made plain early in “Rosewater.” While he’s covering the election before being arrested, Bahari (expertly played by Gael Garcia Bernal) gives an interview to one of Stewart’s colleagues in which he jokes about being a spy. Later, in prison, he will try to explain to his brutal interrogator (excellent Kim Bodnia), a man he nicknames Rosewater for the cologne he wears, that this was all a joke and “The Daily Show” is satire, not news.

The concept of spy talk being offered up for laughs, though, is obviously one that Rosewater can’t grasp. And no wonder: it’s entirely outside the frame of reference of a pious torturer whose life is dedicated to the defense of Iran’s theocracy and its Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei. In one sense, the two mindsets we see colliding in that interrogation room–one medieval, one modern–form the crux not only of “Rosewater”s drama, but also of Iran’s ongoing struggle over its identity and place in the world.

After a prologue showing Bahari’s arrest, the film’s first 40 minutes detail what led to it. In London, Bahari leaves his partner Paola (Claire Foy), who’s pregnant with their first child, for what both assume will be a brief trip to Iran to cover its elections. In Tehran, people are in a fever-pitch of excitement over a contest that pits hard-line sitting president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad against his popular reformist challenger, Mir Hossein Mousavi.

As Bahari sees, Mousavi has strong support among young, educated and urban Iranians, while Ahmadinejad, in addition to appealing more to the poor and unlettered, has bolstered his support with massive government hand-outs. Though Mousavi has been leading in the polls, there are ominous signs on several fronts. Supreme Leader Khamenei, who should remain neutral, has titled toward Ahmadinejad, and in the campaign’s one debate, Ahmadinejad adopts gutter tactics by smearing Mousavi’s wife.

On election day, Ahmadinejad’s forces announce the results even before the polls close: their man has won in a landslide. Mousavi’s supporters naturally suspect a massive fraud and begin protesting immediately. Using a mix of documentary and dramatized footage, Stewart and editor Jay Rabinowitz (abetted by ace cinematographer Bobby Bukowski) construct a riveting chronicle of the following days, when, as the world watches via TV news and social media, more than a million Mousavi supporters–wearing green, a color associated with Islam–march in the streets claiming their votes have been stolen. It’s an uprising that shakes the Islamic Republic’s foundations.

In his book, Bahari says he later gained information that, a year before these events, Iran’s Revolutionary Guards devised a plot in which he and a few others would be designated as agents of the West attempting to stage a “color revolution” in Iran. The film doesn’t indicate this. Rather, it hints that he was targeted due to filming and disseminating images of protestors being gunned down as they attacked the pro-government Basij militia HQ. (This turn from peaceful to violent protest was crucial, and it’s unclear whether it was sparked by the government’s thugs or agents provocateurs from the MEK, an Iraq-based Marxist cult that allegedly has worked with the Mossad.)

Once he’s in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison, and under the harsh control of Rosewater, it’s obvious that Bahari is in for an ordeal. His interrogator has been given marching orders: he must gain the reporter’s admission of having worked for foreign intelligence services and incriminate others for doing the same.

Although in Bahari’s account he was beaten continuously (his face was spared because his captors knew they wanted him on camera), Stewart downplays the physical violence and concentrates instead on the psychological pressure that, even during the Shah’s time, Iranian interrogators knew was more effective in breaking down their victims.

In solitary confinement for days that turn into weeks and then months, Bahari has no other human contact besides Rosewater, who taunts him that everyone he knows outside has abandoned him. So he devises mental games to shore up his sanity, and has imaginary conversations with Paola as well as his late father (Haluk Bilginer) and sister (Golshifteh Farahani), both of whom endured torture and long prison sentences under the Shah.

There are a few lighter moments along the way, as when Bahari, sensing how much of Rosewater’s cruelty owes to sexual repression, tantalizes him with made-up stories of erotic massages he’s received in New Jersey (which Rosewater envisions as sin central). Yet most of Bahari’s experience is torturous both literally and figuratively, and eventually he decides to give the regime’s cameras the fantasy conspiracy stories they want, in hopes that they’ll let him go home to see his child born.

My one real gripe with Stewart’s script is that it doesn’t make clear that Bahari (according to his own account), though admitting to “media espionage,” did not name names, i.e. implicate reformist leaders, fellow journalists or others, as his captors wanted him to. This is a very important point in his decision to cooperate with their televised “confession” of fabricated malefactions.

On the other hand, Stewart’s script offers some very smart additions to Bahari’s account. In one scene, he provides a recollection (as Ben Affleck did in the prologue of “Argo”) of the C.I.A.-backed coup that overthrew Iran’s democratically elected leader in 1953–a canny reminder that Iran’s suspicions regarding the West are not all paranoid fantasies. In another scene, he reveals that Bahari’s father was imprisoned for being a Communist and allows Maziar to challenge his self-righteous dad with the observation that he devoted his life to the Stalinist system that produced the gulag, a model for Iran’s torture mills.

In a sense, it’s when Maziar can free himself from his father’s heroic image that he is really free to go home, notwithstanding the huge international outcry that helped secure his release. Unlike his father, he’s not prepared to sacrifice everything for an abstract ideal. His victory will lie in making it back to his wife and daughter–and living to tell the tale.