The first audible sounds in Kyle Henry’s “Rogers Park” will be instantly familiar to any true Chicagoan. As the opening credits materialize over a black screen, we hear waves lapping against the shore of Lake Michigan. Though the body of water is infinitesimal when compared to those accompanying either coast, its horizon appears infinite, a refreshing change of scenery from the claustrophobic confines of downtown. It’s nearly impossible to walk along the lake without reflecting on one’s own place in the vast expanse of space and time. The private epiphanies one has while peering out at the water can simultaneously conjure a sense of loneliness, as well as a connectedness with fellow wanderers strolling along the same path.

Three of the Windy City’s finest filmmakers have recently made pictures that could’ve been dreamed up during a walk on the lake. Each could easily be deemed a love letter to Chicago, yet none of them devolve into honey-hued travelogues. Michael Glover Smith’s 2015 debut feature, “Cool Apocalypse,” utilized crisp black-and-white imagery as well as Aliotta Haynes & Jeremiah’s classic tune, “Lake Shore Drive,” to portray the nostalgia of remembered passion. Two couples are juxtaposed in the film—one brimming with youthful excitement, the other well past its expiration date. Only gradually do we realize that when the older couple looks at the younger one, they are seeing reflections of themselves. Stephen Cone’s 2017 film, “Princess Cyd,” ends with a startlingly poignant sequence at the lake, as a middle-aged woman conveys her love for her formerly estranged niece during a phone call of few words and incalculable meaning. Now arrives Henry’s “Rogers Park,” a drama bookended by pilgrimages to the lake as it undergoes the cycle of a year. Though each of these films are distinctive in their vision and nuance, they could form an unofficial trilogy, linked by their ode to the fragility and vitality of human connection in an era when technology has been prone to isolate us in a comfortable cocoon of solitude.

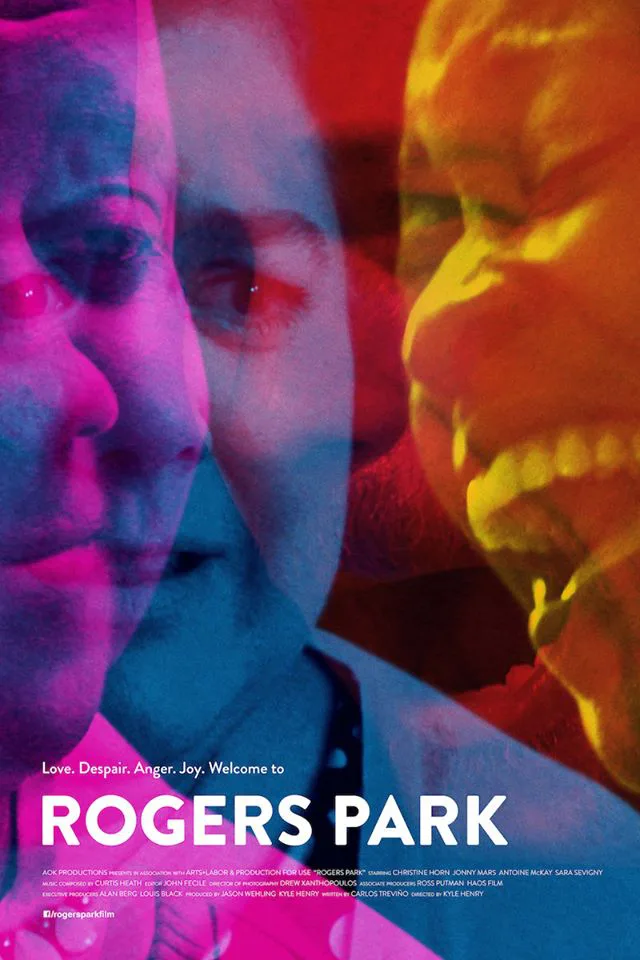

“Rogers Park” could be described as the story of two couples, but as the film’s fragmented poster suggests, they are, in fact, four lonely souls uneasily sharing the same orbit. All initially appears content between Zeke (Antoine McKay) and Grace (Sara Sevigny) as they celebrate their tenth anniversary while surrounded by friends. Yet a dark cloud brews over the gaiety as soon as Grace’s brother, Chris (Jonny Mars), enters the party, wholly unable to participate in small talk without slathering every syllable in morose self-pity. Once toasts start being offered, Chris decides to voice his own congratulations before turning on a dime into pure rage, unleashing an embittered, inarticulate rant that gets him and his wife, Deena (Christine Horn), swiftly kicked out.

Cinematographer Drew Xanthopoulos gives the actors very little room to hide, often framing their faces in extreme close-up during bracing moments of emotional nakedness. There are echoes here of Cassavetes’ most agonizing stretches in “A Woman Under the Influence,” as casual pleasantries detonate into a fiery inferno of resentment. One of the masterstrokes of the script by Carlos Treviño is in how it allows each pair of wounded lovers to mirror the other, as their relationships progress in opposite directions. What is true today may have looked impossible a year ago, as hinted by the snippet of a news show we hear Chris listening to during his day job at the library. The reporter notes that Ted Cruz earned support during the 2016 election by criticizing Donald Trump’s “reliance on celebrity,” and concludes that the billionaire’s chances of landing the Republican nomination are unlikely at best, as evidenced by his “Magic 8-Ball.”

Nothing that occurs in the final scenes of “Rogers Park” would’ve seemed probable at the beginning, and it is a testament to the filmmakers and their superb cast that this story arc doesn’t come across as mere trickery. Henry and Treviño have a keen ear for how the tone of a spouse’s voice can contradict what they’re saying, applying pressure even as the words attempt to calm. While the film’s turbulent scenes are the most potent, there are quite a few funny moments as well, some of which spring directly from the mounting hysteria. Zeke’s demanding work as a real estate broker compounded with his escalating financial problems have severely weakened his ability to fulfill his wife’s needs. Every time he tries opening up to Grace about his exhaustion, she continuously dismisses the truth of his feelings, insisting that her husband “get over” himself. Yet Grace is equally incapable of overcoming the hatred she harbors for her late father, which Chris demands that she “get over” as well.

The abuse that Grace endured from her father obliterated her ability to forgive him during his last years, forcing Chris to do the caregiving while she paid the hospital bills. She prides herself on the discipline she enforces with a tender hand as a preschool teacher (we see her encouraging students to work out their problems “at the peace table”), and argues that she’s nothing like her father because she’d never hit children. However, her claim that she doesn’t “play mind games” prompts a knowing scoff from Deena, who has just been on the receiving end of her sister-in-law’s meddling. Deena is, in many ways, the healthiest member of this foursome, in part because her disbelief in monogamy played a crucial role in the survival of her marriage to Chris. Had she not sought affection elsewhere, there’s no doubt their days would’ve already been numbered.

When stress weighs heavily on these characters’ consciousness, their first inclination is often to shut out the world with headphones or earbuds. As soon as Chris chooses to silence his own self-curated soundtrack by engaging with others, he finds a potential answer to his woes. His sessions with a therapist lead to the film’s most haunting sequence, as we unknowingly slip into one of his nightmares, a poetic illustration of the baggage he’s continued to carry, courtesy of his dad. Eventually he opens up about a revelation that the old man had on his deathbed, awakening just long enough to say, “Son, I’m neither good nor bad.” The fact that this sudden belief brought the wretched patriarch closure makes Chris all the more frustrated, but within that statement lies the bittersweet truth of the movie. Only when we accept the entirety of ourselves, flaws and all, do we have a prayer of earning a place at the peace table.