An extended scene about halfway through Stephen Cone‘s “Princess Cyd” is a perfect illustration of what he does so well as a director. A group of friends gather twice a month to eat, drink, and read excerpts of literature to one another. Everyone comes with something prepared. One person reads the famous final pages of James Joyce’s The Dead. An old woman reads Emily Dickinson’s poem starting with the line “There’s a certain Slant of light.” Excerpts from James Baldwin, Thoreau … In the room is a palpable space of intent group focus, the scene perfectly evoking the pleasure of the ritual for everyone involved.

Cone captures the atmosphere of groups, and groups in particular contexts, the fluctuating alchemy of messy collectives. His gift with ensembles puts him in rare company with directors like Jonathan Demme and Jean Renoir, directors comfortable with sprawl, “mess”, letting things develop as they come. Cone treats each moment with patience—stepping back, allowing it to breathe, find itself. The actors in his films—not just in “Princess Cyd” but his previous features (“The Wise Kids” and “Henry Gamble's Birthday Party“)—make us believe these people have known one another forever.

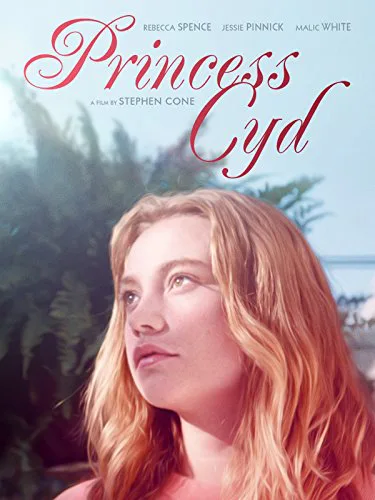

Whereas in “The Wise Kids” and “Henry Gamble,” the ensemble is the star, “Princess Cyd” features a main character as the focal point, a strong, freckled, teenage girl named Cyd (short for Cydney), who goes to stay with her aunt Miranda (Rebecca Spence) for three weeks. Miranda, a famous author, still lives in the Chicago home where she and her sister (Cyd’s mother, now dead) grew up. Why Miranda hasn’t been a part of Cyd’s life at all isn’t revealed until near the end of the film, but it’s a a buzzing subtext.

Teenagers are often shoehorned into types by lazy screenwriters, unimaginative directors, etc. It’s easier, I guess, to use shorthand: jock = jerk, pretty girl = mean, bookworm = nerd. Cyd, though, is a mixed bag. She plays soccer at school, she is unselfconscious about her body, she’s curious about some things, totally indifferent about others. “I don’t read,” she informs her literary aunt, who struggles to maintain a neutral expression in the face of such a shocking admission. Cyd is not neurotic about what she wants (witness her behavior at the tail-end of the literary reading party), but there’s a blankness there somewhere, a lack of continuity with her past, dating from her mother’s death. She barges into the carefully constructed world of her more reserved aunt, asking abrupt questions, sometimes as a rude interruption. Miranda fields Cyd’s bull-in-a-china-shop questions gamely, but it’s awkward. How on earth is she supposed to relate to this bouncing blonde athlete who isn’t even embarrassed that she doesn’t read?

On the first day of Cyd’s visit, she goes into a coffee shop and makes eye contact with an androgynous fluffy-Mohawked barista named Katie (Malic White). Whatever Cyd sees goes to her core, there’s a pheromonal chemistry-click, seemingly reciprocal. Cyd has a boyfriend back home, but is blase about it when he’s mentioned. With Katie, though, the confident Cyd disintegrates into a helpless girl with a crush. The two start hanging out, and it’s clearly the beginning stages of a courtship. Cone treads lightly here. He is interested in the feeling of things, the impressionistic aspect of love and attraction: hair and sunlight and laughter, the vertigo of butterflies in the stomach. His style is gentle and unobtrusive. Cyd hasn’t been with a girl before, but she doesn’t question her attraction.

One of the things “Princess Cyd” does really well is gently allow for the space that opens up between people—and in that space everything is okay. Love isn’t just neurosis. Love is also comfort and belonging. Cyd doesn’t need to change herself to be “worthy” of anyone. Maybe this space between people—the same space in the group literary-reading scene—is love. Letting others contribute to you, listening to others, not just focusing on what you will say next. Perhaps to those more accustomed to the peaks and valleys of plot/conflict/climax, “Princess Cyd” will seem too leisurely. But its leisurely quality—its disinterest in “pumping” things up, its focus on the small yet vivid spaces of listening, understanding, struggle, identity—is its greatest asset.

The scenes between Cyd and Miranda play out on a parallel track to Cyd and Katie’s relationship. The aunt-niece dynamic very well could have followed the cliched rule book: Boisterous Cyd teaches repressed Miranda to loosen up, and bookworm Miranda teaches Cyd to appreciate the written word! While some of these elements do show up, Cone resits putting the characters into a simplistic dialectic. Neither needs to become more like the other in order to be a “well-rounded” person. (“Well-rounded” people don’t make interesting dramatic characters anyway.) For Cone, no one point of view is prioritized. (This was what was so amazing about “Henry Gamble’s Birthday Party,” featuring a much larger ensemble.) Miranda wrestles with her reactions to some of Cyd’s behavior and there’s one extraordinary scene where she calls her niece out for making a rude comment. This is a woman whose wifi password is “Hawthorne1850” (1850 being the year of the publication of “The Scarlet Letter“). Writing Miranda off as a spinster who needs to get laid is deeply disrespectful, and Miranda asserts her own equally valid Self in reaction. There are all kinds of ways to find pleasure in life. Sex is only one of them. You don’t realize how positional most films are, how they push audiences to think a certain way about characters/story/conflict, until you see a film like “Princess Cyd,” until you see how Cone presents his characters and then steps back, allowing them to work it out for themselves.

There are conflicts in “Princess Cyd,” but they’re on a low boil. One of the pluses of Cone’s approach—if you’re open to it—is you are sometimes confronted with your own preconceived notions about people. You may look at Miranda, and think immediately, “Oh, okay, I know who that woman is.” You would be wrong. The same for Cyd. “Oh, okay. Bored teenager sunbathing in a bikini. I know who that is.” Again, you would be wrong. There’s a great line in Philip Barry’s “Philadelphia Story”, where Tracy Lord, who has lived her life in imperious judgment of others, finally “gets it,” and says to her cynical friend: “The time to make up your mind about people … is never.” What a concept.

It’s not easy, what Stephen Cone does. If it were easy, we’d see it more often.