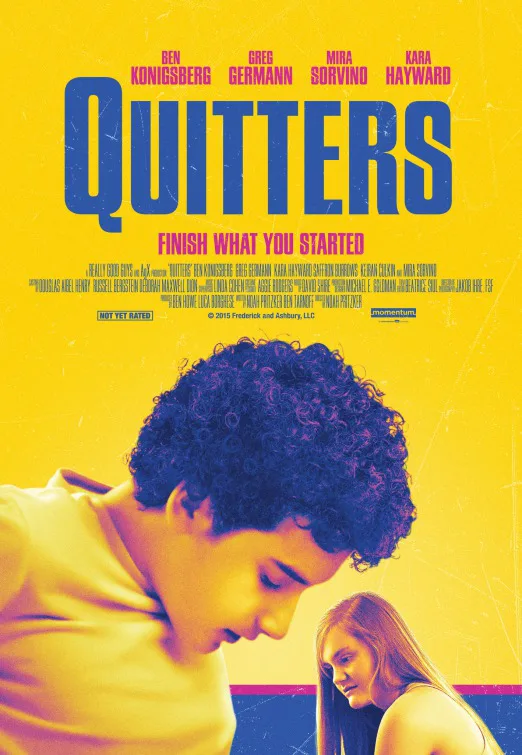

It’s not fun following teenage kid Clark (Ben Konigsberg) around for an hour and a half. Clark is the lead character in Noah Pritzker’s debut feature “Quitters” (Pritzker co-wrote the script with Ben Tarnoff), and he is manipulative, passive-aggressive, and a user with zero sense of humor. Teenagers are often annoying, of course. And teenage angst and peer pressure and the newness of some experiences make them all act a little nuts. But Clark is a horse of a different color. Konigsberg, to his credit, does not soft-pedal any of Clark’s personality flaws, a remarkable accomplishment for such a young actor. But, still, “Quitters” is a challenging and joyless experience. The title of the film is accurate. Everyone here quits: on themselves, on situations, doing drugs, staying in relationships. Considering his selfish parents, it’s no wonder Clark has made an art out of bailing (often with great cruelty) when things get tough.

Clark’s mother (Mira Sorvino) is in rehab for prescription-pill addiction. (“Technically, your mother’s not an addict. She has a ‘dependency,'”, says Clark’s weak stoner dad, played by Greg Germann). Clark has a crush on a classmate named Etta (Kara Hayward), and when she rebuffs his advances, he responds by dropping her as a friend via vicious condescending email, and then spreading rumors around school that she struggles with depression. Clark cannot stand his father, whom he treats with contemptuous superiority. Clark decides to quit his own awful family and become part of another.

Crashing in the home of friend Natalia (Morgan Turner), he worms his way into the family’s routines and, in a particularly bleak scene, into Natalia’s bed. Saffron Burrows and Scott Lawrence play the parents who welcome Clark into their home without once calling Clark’s dad to see if it’s okay. (It calls to mind that funny line from “While You Were Sleeping“: “Lucy, you are born into a family. You do not join them like the Marines.”)

To be fair, “Quitters” does not plead with us to sympathize with Clark. Pritzker and Tarnoff present him in a very straightforward way, showing us what he does, how he does it and his emotional brutality. “Quitters” also does not turn him into a case study (his mother has a “dependency” and his dad’s a loser, and that’s why he’s this way!) Clark is smart, but he is also lazy. He goes for what he wants, whether it’s a condom he steals out of Natalia’s mom’s drawer, or challenging his teacher Mr. Becker (Kieran Culkin) to give him a better grade.

Sorvino is great in the small role of Clark’s tear-stained, checked-out mother, calling and texting him desperately from rehab, but detached from any sense of real responsibility. Kieran Culkin is equal parts disturbing and endearing as the schlubby Mr. Becker, such a different role than the one he just played in Todd Solondz’s “Wiener-Dog.” Mr. Becker works on a novel in his off-hours, and seems like a big clueless kid himself, hanging out by the microwave, staring at it as it heats up his pizza. He’s tough on his students, but he’s weak too. You can practically see the broken dreams scattered around his feet shuffling down the hallway.

At a certain point, a pretty basic thought comes up: What exactly is the story being told here? The pedestrian style does not help. The scenes look like they’re from a 1980s TV movie, with little to no imagination or tension in the editing or angles. A beautiful piano theme by David Shire is yearning, nostalgic, sweet, all qualities which do not enter into “Quitter”‘s emotional landscape at all.

Fictional characters, even leads, don’t need to be “relatable” or likable. They don’t even need to be sympathetic. What they need to be is watchable, which Konigsberg is. Watching him operate (he doesn’t do it by stealth, he comes right out with it), is fascinating in a creepy way. He takes what he wants, walks away without blinking, and has no compunction about re-approaching people he’s hurt if he then needs something from them. His rear view mirror is filled with burned bridges already. He’s a sociopath in training. Very few actors can be both opaque and revealing at the same time. Alain Delon can do it, but that’s a pretty high bar. Konigsberg struggles a little bit in that department. There are times when the camera lingers on his face, and there is nothing going on; it is impossible to tell what he’s thinking. And it’s impossible to tell if that’s the point. It may very well be.

The teenage discontent and rage plus Clark’s runaway status calls to mind Holden Caulfield in “Catcher in the Rye,” but the comparison falls apart on closer examination. Holden had a sense of humor as well as at least being capable of intimate relationships with both of his siblings, dead and alive. Clark, following the example of his wretched parents, is already way beyond that. The more apt comparison would be Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley from her famous “Ripley” novels (Alain Delon, incidentally, in all his gorgeous chilly cunning, played Tom Ripley in “Purple Noon.”) Clark isn’t as bad as Tom Ripley. Yet. Maybe he’ll turn out okay. I doubt it, but maybe. Maybe he’s just surrounded by quitters, and he senses it, and he hates it.

The film doesn’t say.