Luca Guadagnino has become one of those filmmakers whose direction is a show in itself, and fortunately for him he seems to choose material that benefits from a go-for-broke, dump-the-toybox-upside-down approach. “Queer,” about a gay, drug-addicted American expatriate writer (Daniel Craig) in Mexico City circa 1954, is his second film this year after the hyperkinetic love triangle/sports drama “Challengers“—he seems to be giving one of his heroes, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, a run for his money in sheer productivity—and while it’s more measured, even stately, in comparison, you could never accuse the filmmaker of timidity.

Brazenly mixing period accurate sets and costumes, old-school production techniques (including rear projections and miniature buildings and landscapes) and deliberately anachronistic music choices (including Nirvana needle-drops), “Queer” often suggests a 1980s art house import by an outlaw filmmaker that was just recently unearthed: the kind of film that would slowly build an audience at midnight showings. It also serves up a smorgasbord of explicit homoerotic imagery, surrealism and ambiguity at a time when Western culture seems to be stampeding towards 1950s prurience, fascist-scented literal-mindedness, and corporate self-censorship, “Queer” is a film out of its time in just about every way. That’s what’s invigorating about it.

Adapted by Justin Kurtizkes, who also wrote “Challengers,” “Queer” is inspired by Williams S. Burroughs’ same-named, somewhat autobiographical novel, which was written in the mid-1950s as an extension of his controversial Junkie but was more or less abandoned by its author after Junkie was censored by its publisher. The latter was finally issued in an unexpurgated version (and retiled Junky, with a “y”) in 1977. At that point, post-counterculture and deep into ‘7os malaise, the public more amenable to its descriptions of drug use and same-sex trysts. People had also had two decades to get used to the idea of William S. Burroughs, the writer and the brand, an elderly bard with a Midwest accent, speaking incantatory epigrams, with or without dissonant music backing him up. Twelve years later, at the urging of an agent who had scored a lucrative deal with a new publisher, Burroughs dug Queer out of his discard pile and published it, too, which made it a literally a tale out of its time, thus this film’s aesthetic.

The film feels dislocated stylistically and temporally as well as geographically. The knowingly modern touches and frequent, almost Brechtian distancing devices in Guadagnino’s adaptation (including an extended jungle sequence that was either shot entirely in a studio or lit to look as if it was) mark “Queer” as the product of a contemporary consciousness, by an artist who speaks fluent Internet and can direct in meme-able images. (I bet you’re going to be seeing a lot of reproductions of the moment where the two lead characters react to a frightening though clearly fake serpent.)

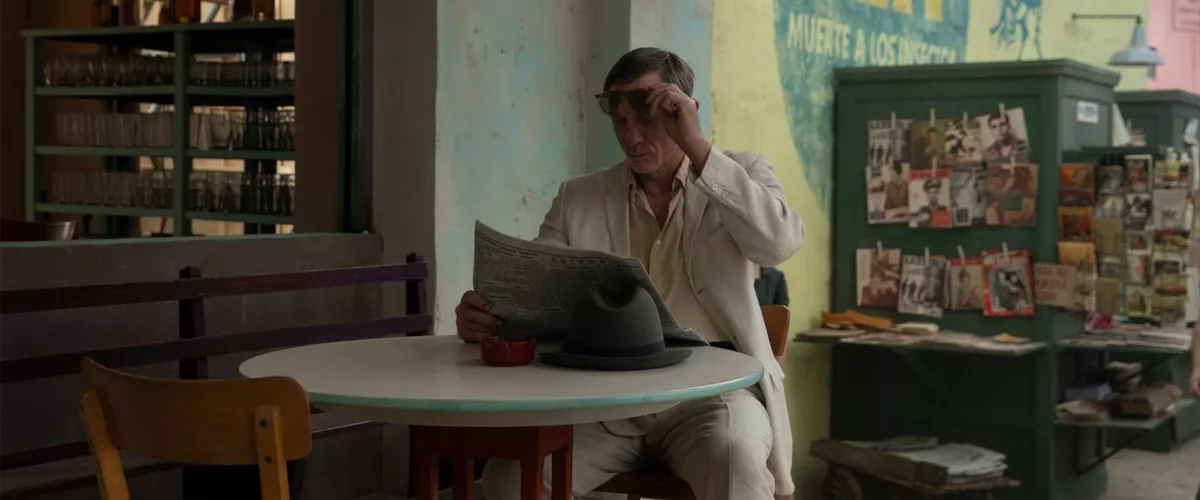

The movie adopts a sort of neo-noir tone at first. Craig’s character, William “Bill” Lee, is a handsome and fit but evidently middle-aged writer who seems to be wasting away in Mexico City, spending most of his time high on smack and drunk on cheap booze and trying to pick up younger men, cigarettes tracing the air to punctuate his witticisms. His best friend, the barfly Joe Guidry (Jason Schwartzman, in another of his recent performances where he’s almost unrecognizable), is the court jester to Bill’s self-exiled and self-regarding king. Bill is infatuated with the young and handsome American Eugene Allerton (Drew Starkey), who, with his little round glasses and compact, zero-body fat frame that makes a perfect rack for his tight-cut clothes, could be the secret kid brother of Guy Pearce’s character in “L.A. Confidential.”

The movie doesn’t have a plot so much a loose accumulation of incidents that ultimately add up to a kind of story. It’s one that happens mainly internally: mostly to Bill, as he tries to first figure out whether Eugene is gay, and if so, whether he’s figured it out and/or acts out, openly or privately. Eugene gives Bill what seem like unambiguous looks of interest, sometimes accentuated by languorous slow-motion, only to walk past Bill in the local bistro and then spend all his time with a woman who might or might not be his girlfriend while casting glances at Bill that seem to last longer than casual glances but might mean a lot of things. The glacially gradual and chaste courtship between the two men, practically a slow dance that leaves Bill adrift in deniability, forms much of the film’s first section. They do hook up with an extended, real-time enactment of physical passion that hasn’t been seen in a mainstream film with a major star (James Bond, no less!) in some time.

And from that point on, “Queer” becomes a sort of foolish love story that grows increasingly destructive (of Eugene) and self-destructive (of Bill, though he’s a destroyer as well). He is benevolently condescending towards the schlubby Joe, who keeps picking up young men who steal from him after they’ve had sex with him, but if you look at the long arc of his experience, how different is he from Joe, apart from the physical assertiveness? He’s just as much a prisoner to his drives, and throws himself after an incarnation of the younger self that he can’t admit is ancient history.

Aspects of this story connect with Thomas Mann’s novel Death in Venice and Luchino Visconti’s film version, in which a middle-aged artist becomes fixated on an ideal of perfect beauty that happens to take the form of a too-young boy, an obsession that he is horrified to realize, too late, as sexual and wrong. Eugene is a twenty-something adult, sexually experienced and capable of making his own choices, but there’s a whiff of daddy issues to his willingness to pair up with Bill, and as their relationship progresses, Eugene seems increasingly disgusted with himself for having gotten into this predicament, though he avoids stating what our eyes can plainly see. Bill, too, seems to know what a disaster they’re in, and starts to try to hold onto Eugene just so he won’t have to deal with having lost him.

In time, the movie divests itself of any pretense of restraint or control and goes boldly and very deliberately into absurdism, showing the men losing themselves in each other and in drugs and losing their minds. They ultimately end up in the darkest reaches of a rainforest searching for an experimental hallucinogen that might give Bill the power of telepathy, a frequent in his conversations that you feel pretty sure is a setup for something. However, there’s no way to anticipate exactly what the delivery will be (know that this is not the book). Leslie Manville plays the crazed chemist who can unlock the secrets of the drug. She lives in a cabin with a much younger companion who amounts to a cult of one. She is rarely seen without a firearm and terrorizes people mentally as well as physically. She tucks the movie into the crook of her arm and walks off with it. Grand theft cinema.

Craig is a revelation in a justly praised lead performance, accessing his character-actor core while infusing the role with trace elements of the movie star phase of his career (which he often seems grateful to have left behind). This is the sort of performance that you might have expected to see from an aging but still potent matinee idol from an earlier time, like William Holden in the 1960s and ’70s and Clint Eastwood in the ’80s. Craig still has that gift for staying on the right side of self-consciousness, letting us understand the self-awareness and sometimes self-flagellation of this man while also letting us see Bill’s rueful amusement at how far he’s willing to let himself fall into degradation (sometimes he swan-dives or cannonballs; the lower he goes, the more he seems to lose his pretensions).

The sum total is a performance of a character whose life is a performance—one that he knows, in moments of reckoning, is seen through by strangers and intimates alike. He’s in mourning for the more formidable character he wanted to be, and for all his eloquence and pretense of hard-earned wisdom, he may be only dimly aware of his grief.

Starkey equals Craig in invention and dedication. His achievement is in some ways more impressive because the character is basically a passenger in a car being driven on an epic journey by a madman. He could get out at a lot of different points but can’t seem to put his hand on the door handle. Eugene Allerton is reticent and undemonstrative, aware of his own handsomeness and not afraid to use it but not bold enough to totally own it. He’s grappling with inner turmoil even when he’s relaxed. You can read his thoughts even without the miracle drug because the actor’s face is an open book.

I don’t know if “Queer” can ever be accused of going too far because it doesn’t set any limits for itself, including those of tone or taste. It’s fun to watch it push itself to be more and more goofy-ridiculous and gothically excessive as it goes along, with prostheses and puppetry and CGI, until the movie begins to crack apart and deconstruct itself, becoming a junkie reprobate’s answer to “2001: A Space Odyssey,” complete with a sequence that’s a poetry-of-flesh riff on the Stargate sequence in which the astronaut Dave Bowman goes behind the infinite. That might sound like an absurd claim if you haven’t seen “Queer.” But if you have, you’ll see the resemblance and perhaps hear “Thus Spake Zarathustra” in the back of your mind as the film leaves our world and grasps after the cosmic like an addict trying to fish a dime bag out of a storm drain.

Is this movie too much? Absolutely, in the way that nearly all of this director’s movies are too much; which is to say, the too-muchness is the point and the artist never promised us hand-holding and whispered endearments, but something you will have to have a strong reaction to, even if a part of you wonders if it is still somehow not enough. This is the colorful adults-only graphic novel answer to David Cronenberg’s phantasmagorical, borderline steampunk Burroughs adaptation “Naked Lunch,” with its own staging of the most horrifying moment in Burroughs’ actual biography. I think it knows it’s that, and revels in knowing it. You can imagine Guadagnino chuckling to himself when he slows the film to a crawl and seems to deliberately try to frustrate us. It’s a flex, and I like it because movies with major stars in them rarely flex this way anymore. His films look as slick as top-dollar TV advertisements but have a streak of gutter poetry, and they dance. The meanings are in the motions. The motions are the point.