“P.S.” is the second movie in two weeks to use reincarnation as the excuse for transgressive sex. The earlier film was “Birth,” in which a woman in her mid-30s becomes convinced that her dead husband has been reincarnated as a 10-year-old boy. Now comes “P.S.,” in which a woman in her late 30s is struck by the uncanny resemblance, in name and appearance, between a 20-year-old student and the boy she loved when she was that age. The age gap makes both relationships problematic; “P.S.” involves sex, while “Birth” prudently sidesteps it.

Both films are fascinating because they require us to see the younger character through two sets of eyes — our own, which witness an attractive woman drawn to a younger male, and the women’s, which see a lost love in a new container. “Birth” considers the possibility that actual reincarnation is involved, while “P.S.” is willing to consider the possibility of an amazing coincidence. In “Birth,” it is the little boy who insists he is the dead husband, and tries to prove it; in “P.S.,” the woman is struck by the uncanny similarity between a student and the young man she once loved, and tries to prove it — to him, and to a friend her own age who once loved him, too. That both her dead boyfriend and the young student are named F. Scott Feinstadt seems too good to be true. Even, indeed, if only one were named F. Scott Feinstadt, it would be a reach.

Watching these movies, we are fascinated by the disconnect between romance and reality. If the 10-year-old boy in “Birth” really is the dead husband, what then? The older woman (Nicole Kidman) actually suggests at one point that they wait until he comes of age, and then, well, what? It might have been wiser for her to say: “It’s been 10 years since you died. Life goes on. You should grow up and find a girl your age. Look at it this way: You’re the first person in history who gets his wish to be 10 again, knowing what you know now.”

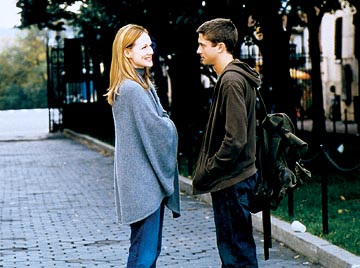

As for “P.S.” and the new F. Scott (Topher Grace), there’s little doubt in the mind of Louise Harrington (Laura Linney) about what she should do, which is to take him home in the middle of the afternoon so they can have safe sex immediately. That she is a Columbia University admissions officer and he is a student applying for admission creates an ethical conflict, but should ethics stand in the way of earthshaking metaphysical lust? We would all agree that ethics certainly should not, although of course if a 39-year-old male admissions officer were to sleep with a 20-year-old female applicant, castration would be too good for the fiend.

These logical considerations are not much discussed in “P.S.,” although one of the best things about “Birth” is that the woman’s family thinks she’s crazy and her mother threatens to call the cops. In “P.S.,” reincarnation is not insisted on, and while Louise sleeps with F. Scott because she wants to relive her treasured memories of first love, F. Scott sleeps with Louise because he can. Both genders are programmed by eons of Darwinian genetic strategy, and so we believe them, and because Linney and Grace are sexy and play well together, the age gap is not a barrier so much as additional seasoning.

In “Birth,” it must be admitted, the 10-year-old doesn’t bring much to the party. He stands there like a little scold, insisting on his identity and completely failing to see the humor in his predicament. F. Scott, on the other hand, is a wiseass who treats Louise with an informality bordering on rudeness; she likes this, because it reminds her of the other F. Scott, and because it means she is being treated more like an equal than like an older authority figure. Louise has been saving up for a long time for the opportunity to get medieval on some guy. Like the 40ish Kim Basinger character in “The Door in the Floor,” who has a wild fling with a 16-year-old boy (who resembles her dead son, of course), she brings great appetites to the task.

Louise comes supplied with an ex-husband, a brother and a best friend who complicates matters. The ex-husband, inevitably named Peter (Gabriel Byrne), has decided he is a sex addict, and is 12-stepping his way to restraint at just that moment when Louise casts it to the wind. Her brother Sammy (Paul Rudd) is a recovering addict with a fund of handy mantras. Her friend Missy Goldberg (Marcia Gay Harden) flies in from the coast to get a good look at F. Scott, and invites him to her hotel suite to get a better look. There is some question whether it was Louise or Missy who loved the original F. Scott first, or last, or best.

The plot mechanisms of these movies are at the service of justifying scenes that would otherwise be impossible, improbable, or criminal. The achievement of “Birth” is to take an entirely unacceptable situation (older woman, child) and make it dramatically possible by inhabiting the young body, so it would seem, with an older man. “P.S.” uses the stunning power of the boy’s uncanny resemblance to the lost love, and “The Door in the Floor” uses the grief of the mourning mother, who is reminded of her dead son by this teenage boy, although that doesn’t exactly explain why she sleeps with him.

Watching these movies negotiate the hazards of their plots is part of the fun. Watching good actresses at the top of their form is another. Because these are not European films like Louis Malle’s “Murmur of the Heart” or Agnes Varda’s “Kung Fu Master,” they depend on plot more than emotion to motivate their forbidden behavior, but they seem to be taking chances even when they aren’t really, and besides, stories like this are gold mines of terrific reaction shots.