Nobody sees the little boy come into the apartment, but suddenly there he is, a stranger in the room at a family birthday party. “I am Sean,” he says. Sean is the name of Anna’s husband, who died 10 years ago. The boy’s name is Sean, but that’s not what he means. What he means is that he is Sean and that when Sean died while jogging in Central Park, he was reborn and now here he stands, age 10.

Since the first two scenes of “Birth” show the death and the birth, we’re prepared for the reincarnation. What I wasn’t expecting was a film that treats it as intelligent, skeptical adults might. They don’t believe in reincarnation. Neither did the original Sean; the movie opens with a black screen and we hear him giving a speech: “As a man of science, I just don’t believe that mumbo jumbo.”

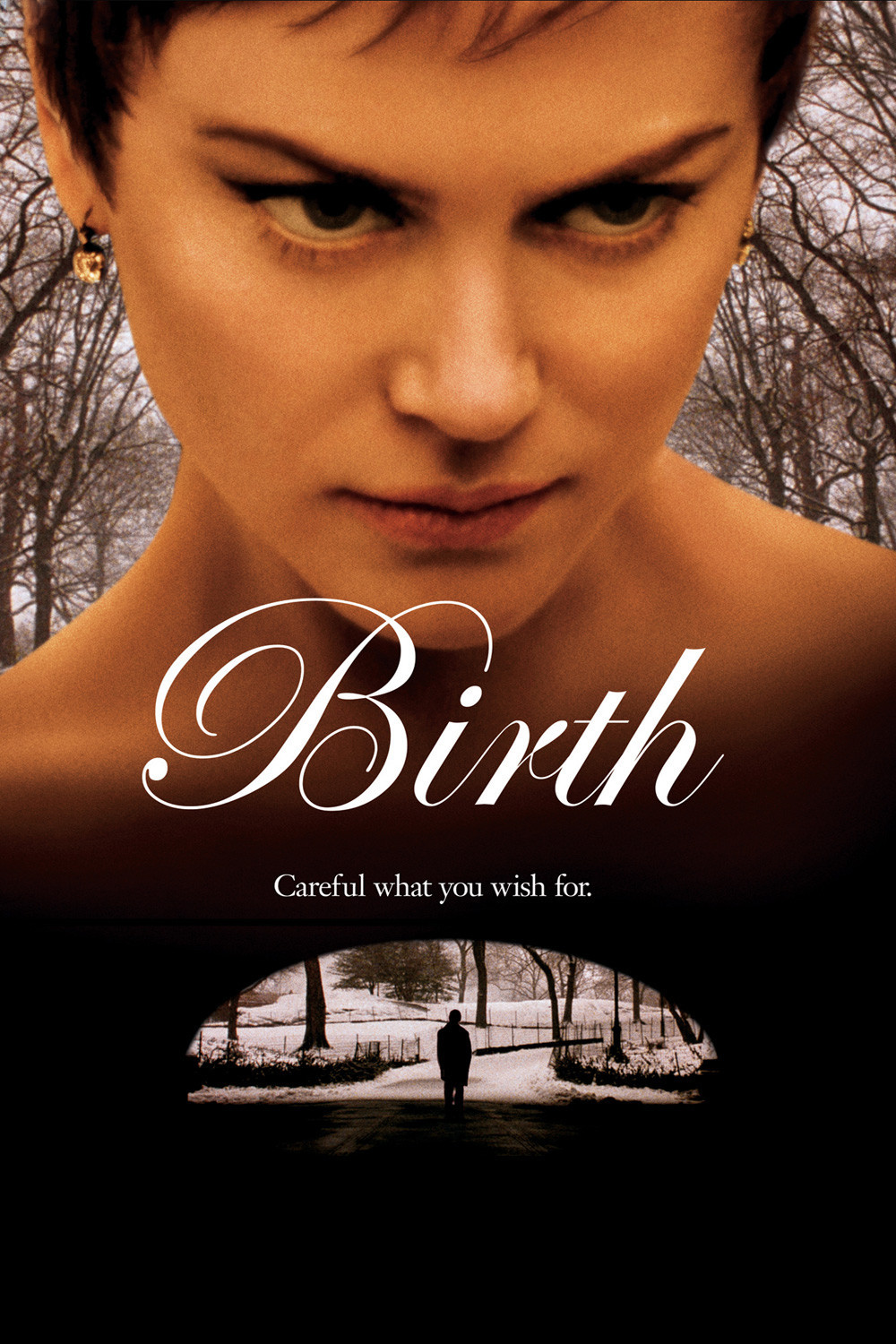

“Birth” is an effective thriller precisely because it is true to the way sophisticated people might behave in this situation. Its characters are not movie creatures, gullible, emotional and quickly moved to tears. They’re realists, rich, a little jaded. At first, they simply laugh at the boy (Cameron Bright). Even when he seems to know things that only her husband would know, Anna (Nicole Kidman) is slow to allow herself to be convinced. She loved Sean and mourned him a long time, but after 10 years it is time to resume her life, and she has just announced her engagement to Joseph (Danny Huston).

Anna lives with her mother, Eleanor (Lauren Bacall), in a luxurious Manhattan duplex. The family includes her sister, Laura (Alison Elliott), her brother-in-law, Bob (Arliss Howard), and her close friends Clara (Anne Heche) and Clifford (Peter Stormare). Since they’re all present when Sean first appears, they’re all involved in the dilemma of what to do about him. Sean’s parents order him not to annoy Anna anymore, but he turns up anyway, solemn and unblinking, an unsettling combination of a kid and a solemn, unblinking presence. When Anna tells him she simply doesn’t believe him, he says, “What if Bob comes to my house and asks me some questions?” “How do you know Bob?” “He was my brother-in-law.” Bob goes and asks some questions, and as the family gathers to listen to a tape recorder of Sean’s answers, it’s clear something exceedingly strange is going on.

Anna becomes convinced, reluctantly, but then firmly, that Sean really is her reincarnated husband. She arrives at this decision, I think, during an extraordinary shot: a closeup of her face for a full three minutes during an opera performance. And then the film ventures into the delicate area of exactly how a woman in her 30s goes about relating to a 10-year-old boy who is or was or will again be her husband. In one mordantly funny scene, they eat ice cream while she asks him how they will live, and he says, “I’ll get a job.” And, “Have you ever made love to a girl?” Well, yes and no. Yes, as Sean One, and no, as Sean Two; one of the film’s mysteries is that Sean seems to be simultaneously the dead husband and an actual little boy.

Much has been said about a scene where Sean boldly gets into the bathtub with her, but the movie handles it with such care and tact that it sidesteps controversy. Anna’s mother, for her part, thinks the whole situation is dangerous nonsense and could develop into a crime. As played by Bacall, Eleanor is tart and decisive. When it appears Anna is considering living with Sean, her mother says: “I will call his mother, and his mother will call the police.” Anna’s fiance, Joseph, is the wild card, reacting first with disbelief and then with restraint, before …

Of course, there’s a lot I haven’t described, including the role of Clara (Heche), Anna’s best friend. The movie goes deep and then it takes a turn, and leaves us asking fundamental questions. There seem to be two possible explanations for what finally happens, but neither one is consistent with all of the facts. At a point when the characters seem satisfied they have arrived at the truth, I believed them, but it wasn’t truth enough for me.

“Birth” is a dark, brooding film, with lots of kettledrums and ominous violins in Alexandre Desplat’s score. Harris Savides’ cinematography avoids surprises and gimmicks and uses the same kind of level gaze that Sean employs. Echoes of “Rosemary’s Baby” are inevitable, given the similarity of the apartment locations and Kidman’s haircut, so similar to Mia Farrow’s. But “Birth” is less sensational and more ominous, and also more intriguing because instead of going for quick thrills, it explores what might really happen if a 10-year-old turned up and said what Sean says. Because it is about adults who act like adults, who are skeptical and wary, it’s all the creepier, especially since Cameron Bright is so effective as the uninflected and non-cute Sean. Like M. Night Shyamalan’s best work, “Birth” works less with action than with implication.