“Policeman,” by debuting Israeli director Nadav Lapid, is a curiously bifurcated film. It starts out telling the story of one group of characters, the policemen suggested by the title. Then, about halfway through, it abruptly shifts to focus on another group, a small band of left-wing radicals. Naturally, the two stories converge toward the narrative’s end, but that doesn’t overcome the sense that the film suffers from a deeper bifurcation: a split between actually saying something about the tricky political and cultural issues it treats, and appearing to do so while shying away from that task’s toughest challenges.

The policemen depicted in the film’s first part are not ordinary cops but a five-man team in the Israeli Defense Ministry’s elite Anti-Terrorism Unit. In other words, they’re assigned not to police regular Israelis but to control Palestinians (a.k.a. terrorists), often by lethal means. The film doesn’t start out explaining this, or showing the men in action; rather it stresses their macho camaraderie with scenes of them bicycling across the desert and engaging in horse play, playful wrestling matches and endless back-slapping at a Tel Aviv barbeque.

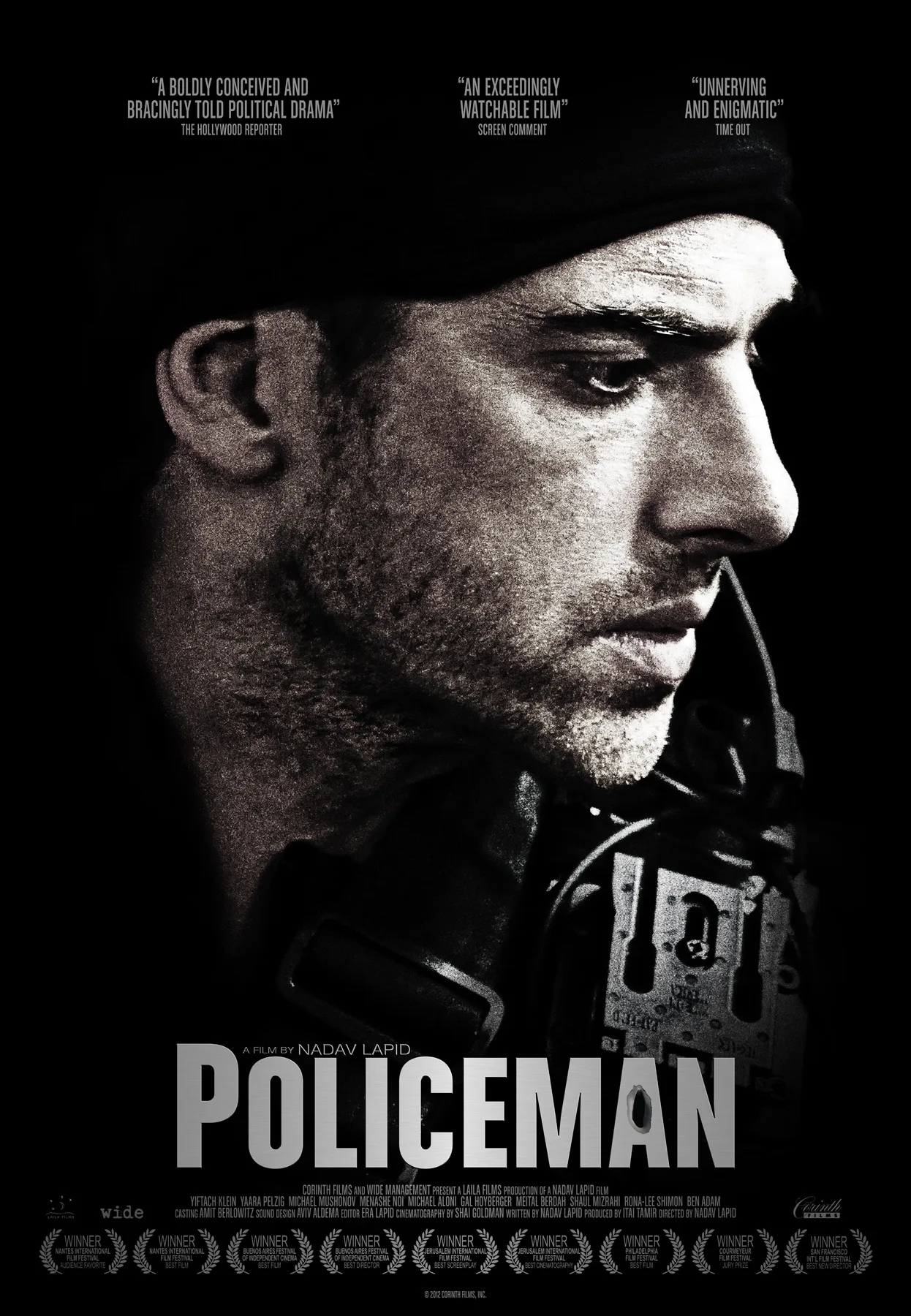

The leader of this group, Yaron (Yiftach Klein), is described as an “alpha male” in the press notes, and the film displays an almost-lipsmacking avidity in conveying his masculine hotness. In one early scene, he puts an upbeat tune on the stereo and dances seductively in his short-shorts for his wife, and us, as if to make sure we haven’t failed to notice his sexy build. But Yaron’s also a guy facing challenges on several fronts.

At home, his wife is in the final stages of pregnancy. While this carries both excited optimism and dramatic anticipation (they know the child will be a girl), it also means he’s not getting laid. At a seaside restaurant, he chats up a pretty waitress and finally asks her age. She says she’s 15. Ulp. Will he or won’t he?

At work, Yaron’s unit is troubled by the knowledge that the leanest of its members has a large growth in his head. An upcoming medical test will determine if it’s cancerous. Meanwhile, the entire group is under investigation for a lethal incident. The press notes describe this as “an unforgivable accident resulting from a miscalculation during a recent rescue mission.” But that’s an obvious attempt to soft-pedal something rather different. The incident, as the film describes it, was not a mission of rescue but to assassinate a “terrorist,” and it resulted in the death or severe wounding of several other members of the targeted man’s family, including a five-year-old boy.

The way out of their legal dilemma, Yaron and three of his fellows decide, is to ask their sick colleague to claim responsibility for the casualties, since his condition means he won’t be prosecuted. But will their ailing comrade agree to the scheme?

Suddenly, we’re out of this world and in a very different one, observing a five-person unit on the opposite end of the political spectrum. They’re a group of radical socialists who’re in a frenzy over the yawning chasm between rich and poor in Israel, the greatest in the developed world, according to one. Lapid first depicts this curious bunch in the desert showing their militancy by blasting apart the only tree in sight with their handguns. Evidently, their dedication to violent action (or narcissistic self-dramatization) trumps any environmental sympathies they might have.

Closer to the sarcasm of Fassbinder’s “The Third Generation” than the romance of Godard’s “La Chinoise,” the account of radical group-think here stresses the collision of personal and political delusions. The band’s one female, a lissome strawberry blonde, is enamored of their leader, a handsome, unsmiling, strangely Nordic-looking guy who seems to have no feelings at all. Meanwhile, she is the object of unrequited infatuation from one of the group’s younger, less Nordic and less commanding members.

While endlessly rewriting and declaiming their manifesto against the rich, the group puts its words into action with an assault on a wedding in a posh hotel where they take several billionaires hostage. The execution of this scheme is, of course, where the radicals converge with Yaron’s unit, which is shocked to find that, for once, the enemies they are wielding their guns against are “not Arabs!”

Obviously, this tale engages many hot-button issues in present-day Israel. But does it say anything particularly incisive or meaningful about their complexity? On the contrary, its ultimate message seems to rest on a kind of glib and simplistic equivalency. “Here in Israel we’ve got fanatical fools on the right and fanatical fools on the left,” it seems to say, “and ne’er the twain shall meet, leaving the rest of us trapped in a hopeless middle.”

But does Lapid really believe that the issue of Israel’s rich-poor divide belongs only to crazed fanatics like his leftist militants? For that matter, does this group resemble any that is active in Israel today? One of the film’s problems as a drama about cultural and political problems is that all of its people seem to inhabit a thankless zone between being actual characters and arch caricatures. That archness leaves the filmmaker in a position of presumed intellectual and moral superiority, from which he can look down not only on his fictional creations but also on the real people who are struggling with the problems he evokes. This may be a comfortable perspective, but it is not an illuminating one.

The film’s stylistic fluency evinces a different kind of superiority. If Lapid learned his skills in school, he clearly aced Art Film 101. Somewhat like Denis Villaneuve’s “Incendies,” a much better film, its combination of deliberate compositions, nuanced cinematography and sharply staged action suggests a director who’s assimilated lessons from Kubrick, Oliver Stone and other master directors. If he evolves a moral vision to match his stylistic savvy, Lapid will be a force to be reckoned with.